Boeing’s engineering credibility was already under fire following the Boeing 737 Max airliner crashes, partial failure of the first unmanned test flight of its commercial crew CST-100 Starliner spacecraft (causing a US$410 million hit to Q4 earnings) and various botched military programmes. But another woe has befallen it. Boeing has removed itself from the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) programme to build a winged first-stage reusable rocket, called the Experimental Spaceplane-1 (XS-1), aka the “Phantom Express”. DARPA accepts that with the withdrawal of Boeing, the project is now cancelled.

Following Phase 1 study contracts in 2014, Boeing beat Masten Space Systems and Northrop Grumman in a competition for the Phase 2/Phase 3 contracts to build and fly the vertically launched space plane’s first stage in May 2017. The company was awarded a US$146 million contract, paid in stages. Boeing also invested its own money in the programme. Masten Space Systems was later given the role of building the Zephyr expendable upper stage.

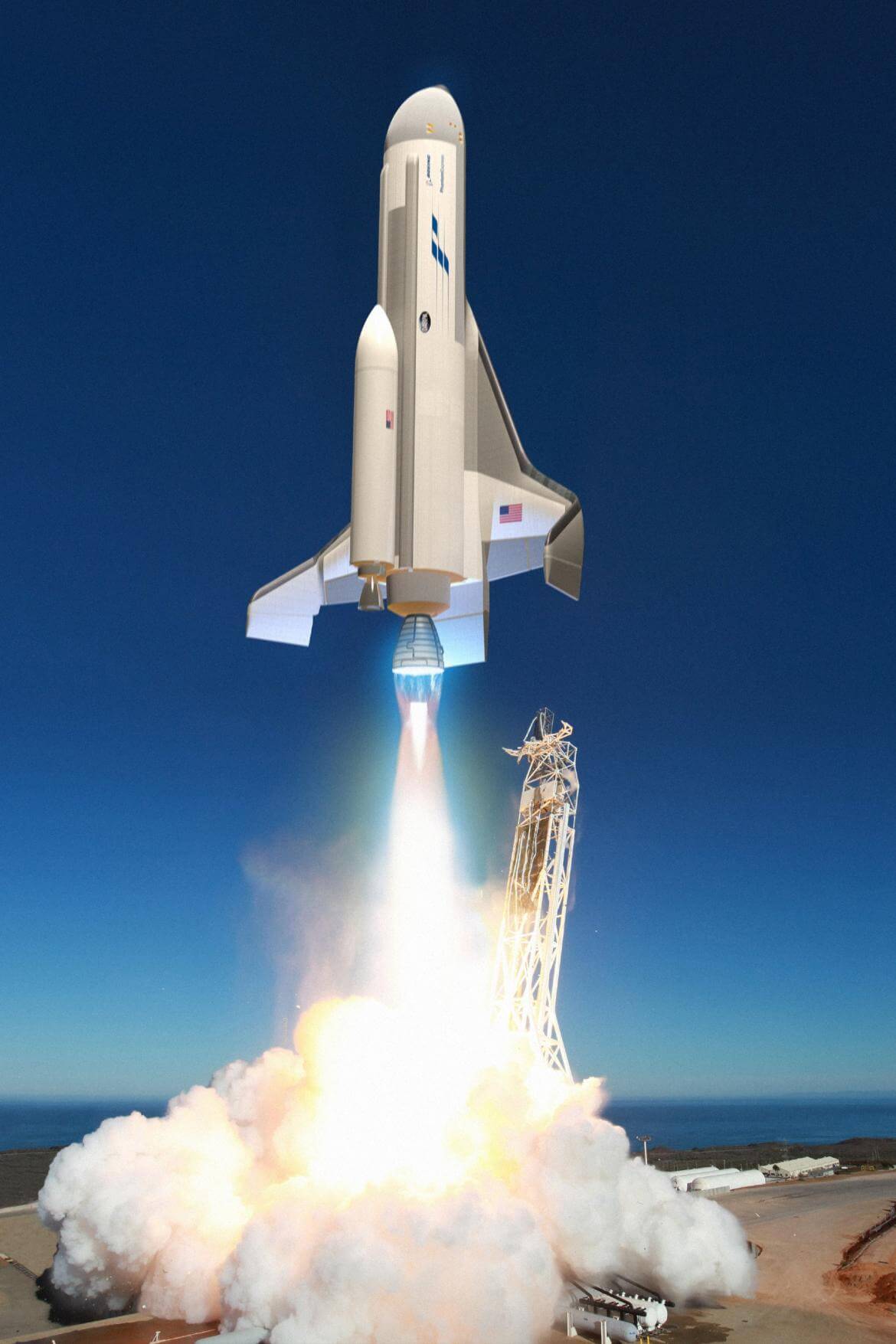

The Phantom Express was an experimental spaceplane and the Zephyr booster was planned to have the capability to deliver small satellites into orbit for the US Military, with a flight rate/cadence as frequently as once a day. The spaceplane was to have been powered by a Liquid Hydrogen/Liquid Oxygen (Lox)-burning Aerojet Rocketdyne AR-22 engine, based on Space Shuttle Main Engine technology. Test firings of this engine have reportedly gone well.

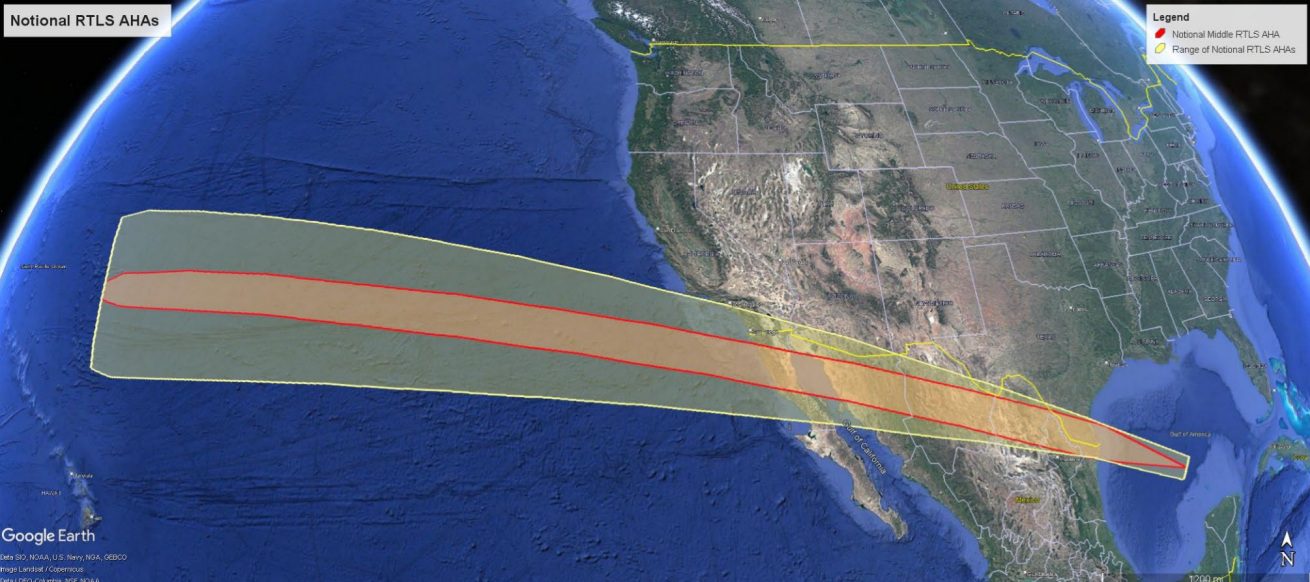

During an operational flight the 30m long spaceplane would achieve a velocity of Mach 10 before releasing an upper stage to take a satellite payload into orbit. The combination was planned to have a payload to low Earth orbit of 1,360 kg.

Comment by David Todd: The exact reasons for Boeing’s withdrawal and the project’s failure have not been disclosed. One suspects that financial struggles at Boeing are part of the story. The reusable rocket plane might also have some technical issues as it struggled to achieve its payload/cost/fast reuse objectives. For example, the XS-1 may have been too heavy (wing structures and associated thermal protection systems tend to be weighty and complicated), and difficult to integrate (as reusable two-stage winged vehicles are liable to be).

While the withdrawal is very embarrassing for Boeing, DARPA should also be ashamed. This failure just adds to the list of launch project failures that DARPA has had over the years. It has spent hundreds of millions of US taxpayers’ money on launch vehicle projects with little to show for it. A prime example came in late 2015 when DARPA’s ALASA (Airborne Launch Assist Space Access) programme to launch a small rocket launcher from an F-15 jet fighter was ended after series of ground explosions. While its drop-off fuel tank and canted engines’ design had some merit, DARPA found out what any 7th grade space cadet could have told it beforehand: mixing liquid fuel and oxidiser in a single tank was a dangerous thing to do. Before that DARPA had launch project failures with its RASCAL (Responsive Access, Small Cargo, Affordable Launch) and FALCON (Force Application and Launch from Continental US) programmes.