According to the Seradata SpaceTrak launch and satellite database, the “final score” for launches in 2020 is 11 launch failures out of 114 orbital attempts. One of these was really a minor partial involving a pair of stuck Lemur satellites on a Vega (only about 3 per cent of the satellite payloads aboard). The overall launch failure rate for the year was slightly above average at just under 10 per cent. Nevertheless, the total of 11 failures made it the worst result in terms of pure events since 1971, which had 17 launch failures. 1982 was the closest in the modern era at 10 failures.

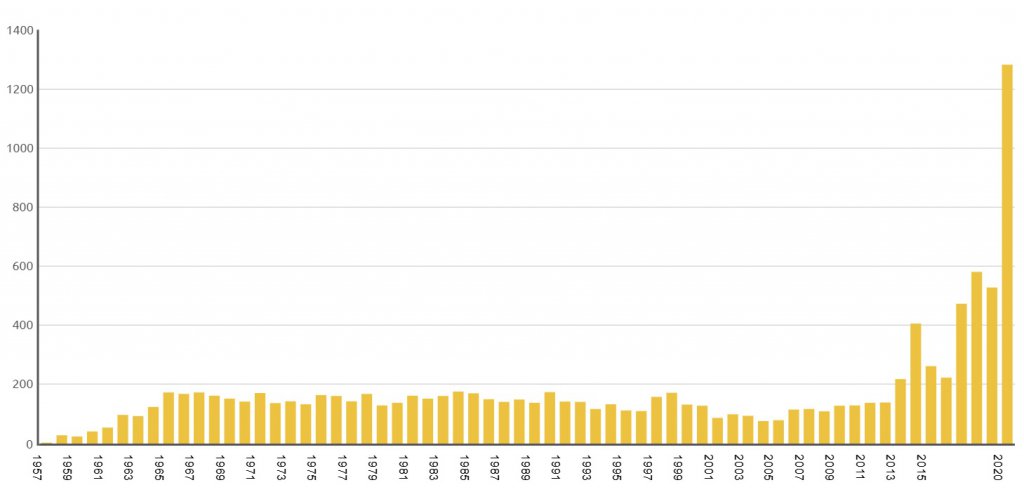

Chart showing the number of Spacecraft launched in a given year shows that 2020 broke the record. Source: Seradata SpaceTrak database

With respect to launch nations, China came out on top – but only just at 39. the USA was a close second at 37 – mainly thanks to SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launches (especially of its Starlink constellation). Russia came a distant third at 15 launches, with France/Europe (via Arianespace) sharing fourth spot with relative newcomer New Zealand (due to Rocket Lab) at 7 launches apiece.

Some 1,282 spacecraft were aimed at orbit in 2020 (19 of these failed to reach any kind of orbit) – historically the largest number ever attempted and more than double 2019’s 528 total or 2018’s 578. This was mainly due to constellation launches (e.g. Starlink).

It was not all brand new rockets. Some returned after a long layoff including Angara A5’s second launch. Courtesy: Roscosmos

When it came to the nationality of the ownership of the satellites launched, the USA easily led the way with 994 spacecraft. However, there was a dramatic change in the number two spot, which was taken by surprise newcomer the United Kingdom at 106 satellites, pushing China into third at 79 and with fourth-placed Russia on a lowly 22. Yes, you have read that right: having been pretty much absent for decades, the UK’s ascendancy to second place rests on the shoulders of its acquisition (with India’s Bharti) of half of the OneWeb constellation.

Maiden launches featured this year included the arrival of Astra Space Rocket 3.0, the Long March 5B, Long March 7A, Long March 8, the Kuaizhou-11 and the Qasad. While some of these rockets – mainly the Long March debutants – were more derivative than brand new, their arrival had a major effect on the number of launch failures as maiden flights traditionally have very high failure rates.

The year’s failures began in February with the launch of an Iranian Safir 2A Simorgh rocket, which failed to achieve orbital velocity, with its Zafar 1 remote sensing/store-forward satellite subsequently falling into the Indian Ocean. The next one came in March when a Long March 7A (CZ-7A) debut launch failed after an apparent second-stage explosion at 52 seconds after lift-off. The Chinese TJS-6 communications technology test/early warning satellite was destroyed.

The third failure of the year probably incurred the most expensive loss. The Palapa N1 communications satellite was destroyed in April when a Long March 3B-G2 rocket fell into the Pacific after its third stage failed to ignite. The satellite was insured for US$242.5 million and the claim was paid.

The fourth launch failure was in May when the maiden flight of the Virgin Orbit LauncherOne air-launched rocket failed after a shutdown of the first-stage engine due to a propellant line rupture. The Starshine 4 student atmospheric research satellite, plus a student payload attached to the rocket, was lost.

Failure number five occurred in July when seven small satellites (Faraday 1 store-forward satellite, the CE-SAT-IB remote sensing satellite and five Flock 4E remote sensing satellites) were lost on an Electron launch vehicle. An electrical connector cut power from the rocket’s battery to the electrically powered turbo-pumps of the Rutherford second-stage engine causing its premature shutdown.

The sixth launch failure, also in July, was on the maiden flight of a Chinese Kuaizhou 11 (KZ-11) rocket when a third-stage ignition failure resulted in the loss of the Jilin 1 High Resolution 02E imaging satellite (insured value of circa US$40 million) plus a small technology test navsat called Centispace-1 S2.

Orbital “launch failure” number seven occurred in September. It was actually a very minor partial one involving two Lemur satellites (out of a total of 65 payloads carried), which refused to separate from the Vega rocket’s upper stage.

The eighth launch disaster was a true failure when the maiden flight of the instrumented Astra Rocket 3 (Flight 3.1) fell back to Earth and exploded on impact on 12 September. The ninth launch failure occurred on the same day: a Chinese Kuaizhou 1A rocket failed losing the Jilin Gaofen 02C high-resolution satellite. Details of this failure are sketchy.

The tenth launch failure (in November) was much clearer and again featured the Vega launch vehicle. The surprisingly uninsured Spanish SEOSat/Ingenio high-resolution optical imaging satellite – with a mission value of circa US$265 million – was lost, along with the French Taranis magnetosphere research satellite. Causation was traced to improperly connected control cables, resulting in a fatal tumble for Vega’s AVUM upper stage.

The final (eleventh) launch failure of the year occurred in December. This was the second flight of the Astra Rocket 3 (flight 3.2) which this time nearly made it. However, it just failed to achieve orbital velocity due to an incorrect propellant mixture ratio in the upper stage.

Astra rocket launch attempt 3.2 lifts off from Kodiak Island…but it did not make it into orbit. Courtesy: Astra Space

With respect to suborbital launches, notable failures in December included an inflight shutdown for Virgin Galactic’s air-launched SpaceShipTwo, one second after its ignition. Thankfully, the crewed rocket plane did manage to glide back to a safe landing.

While also not counted as a true space launch, the very endo-atmospheric launch hop of the SpaceX SN8 test rocket ended in an explosive landing. Mind you, it had done all the difficult bits of the flight up to that point.

With regard to actual orbital launches SpaceX continued to have success with its reusable Falcon 9/Falcon Heavy rocket first/booster stages (SpaceX even managed to refly two of these, B1049 and B1051, for their respective seventh time each in November and December). Some critics noted that these part-reusable launch vehicles had not significantly increased demand for satellite launches overall, and that SpaceX’s high flight numbers were really driven by the need to launch its own Starlink constellation.

Nevertheless, as SpaceX pursues its goal of an all-reusable two-stage launch system in the shape of its Starship/Superbooster combination, competitors have been stung into action and are now taking reusable technology seriously. China, Europe, India and New Zealand (via the Rocket Lab programme) are all undertaking significant development of reusable launch vehicles.

The reusable Falcon 9 first stage B1059 on its fifth flight lands successfully at LZ-1. Courtesy: SpaceX