For Eutelsat, a leading geostationary and low Earth orbit communications satellite operator (with the acquisition of OneWeb), a lack of available launch slots over the next five years is of immediate concern, according to keynote speaker Vijay Thakur, the company’s Satellite Technical Authority. “Are we able to get it (the satellite) up on time?” was the rhetorical question he asked at the Seradata Space Conference on 20 June.

Jean-Luc Froeliger, who oversees the procurement, launch, engineering and operations of Intelsat, agreed – especially as Intelsat will be looking for launches for a new medium Earth orbit (MEO) constellation. The company planned to order 18 satellites in MEO orbit set in three planes inclined at 60 degrees to the equatorial plane, according to Froelinger. These would be able to communicate with GEO satellites via an intersatellite laser communications system. While electric satellites, furnished with low consuming thrusters that do not need to be replenished, do not really need refuelling technologies, Froelinger did acknowledge that chemical propulsion systems would find a use for refuelling.

Caleb Henry, Director of Research at Quilty Analytics, said that only around nine GEO satellites were likely to be built per year, as mainstream space-provided communications moved to other orbits. Nevertheless, there was a niche regional market for GEO satellites. Froeliger had earlier said that smaller GEO satellites were ideal for regional applications and that Intelsat had placed orders for them from Swissto12.

The audience looks on attentively at the Seradata Space Conference. Courtesy: Seradata/Derek Goddard

Connectivity issues at the conference (two speakers joined via Zoom) prompted an observation by William Ricard, Managing Director of E-Space, about the irony of the situation given that the session was about the importance of communication. Although E-space, founded by industry veteran Greg Wyler, had only launched three small satellites to date, it had registered a constellation plan for 320,000 satellites with the ITU via the nation of Rwanda. However, Ricard admitted the eventual number of satellites in the constellation was likely to be just one per cent of that total.

Lorenzo Arona, a Senior Manager at Avanti, drew attention to the latest trend in modern communications that the satellite industry would need to adapt to: the shift to homeworking, which was accelerated by the global pandemic.

Given that LEO satellite constellations have so much redundancy for satellite loss, operators generally do not take out in-orbit insurance – but, with the exception of Starlink, they generally do insure launches at least. Even SpaceX might have second thoughts after one of its recent Starlink Falcon 9 launches had its perigee target set too low for its satellites to survive for very long.

With mainstream space communications increasingly likely to come from different types of orbit, Thakur was asked if Eutelsat would prefer to insure its service rather than just its space assets: “Yes” was his answer.

The launch panel: finding a launch in time

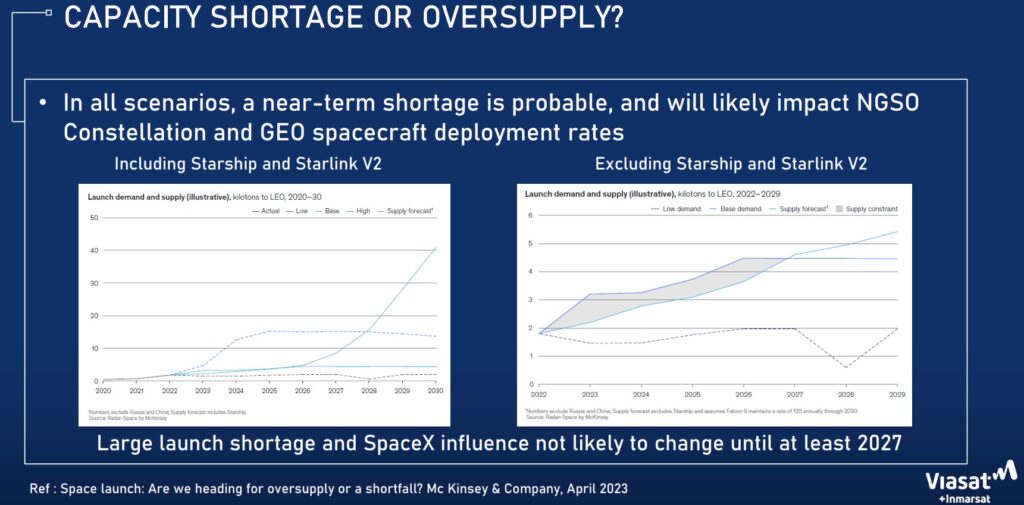

The senior director of spacecraft programs at Viasat and Inmarsat, Marc Behamou, bemoaned how many new rockets (Ariane 6, New Glenn, Vulcan etc) had been delayed from their original, albeit rather optimistic, planned launch dates. He also noted that Chinese and Russian rockets were no longer available for geopolitical reasons. The comment was especially pertinent for the operator as it struggles to find a ride for the third Viasat-3 satellite.

Meanwhile, those rockets already flying, such as Atlas V, Falcon 9 etc, had their already limited manifests booked out by government/space agency, military, or, in the case of SpaceX, their own constellation needs, with that likely to continue until 2028. Behamou also cautioned that there was often a three-to-five-year wait before a new rocket reached full operation after a successful maiden flight had taken place.

He also complained that, with little immediate competition, there was no leverage power on pricing. Nevertheless, after 2028 opportunities might improve especially if the “elephant in the room”, Starship – which may fly 100 times a year with a massive payload capability – became fully operational. However, Thakur warned of the cascade danger of a launch failure of such a dominant player. As it is, many must be praying that Falcon 9 remains reliable given the launch slot shortfall.

The difference between launch demand and supply is badly mismatched until 2028. Courtesy: The difference between launch demand and supply is badly mismatched until 2028. Courtesy: McKinsey via Viasat/Inmarsat

Skyrora XL Courtesy: Skyrora

Some smaller companies hope to fill some of the gaps despite their inability to compete on price. Alan Thompson, of Skyrora, said that his company would soon have its Ecosene (an eco-produced Kerosene)/HTP (High Test Peroxide) Skyrora XL flying from the UK, along with its “Skyrider” orbital transfer vehicle. This would be more of a specialist taxi offering a 315 kg payload to LEO than a SpaceX style bus-to-orbit service. The company, which uses a mobile launch complex dubbed a “spaceport in a box”, planned to have a regular launch cadence in a bid to provide a solution to the current monopoly by SpaceX, Thompson added.

Simon Reed, of the orbital tug service D-Orbit, made a similar point about bespoke “taxi” launches and noted that his firm’s OTVs (Orbital Transfer Vehicles), given the right sensors, might also be able to help with Space Situational Awareness and space traffic coordination.