Farah Ghouri finds out how Aarti Holla-Maini, director of the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs, is faring six months into the job, her plans for the office and why she believes the UN’s sustainability guidelines are the “treaty of our times”

UNOOSA had been without a director for over a year and a half, before Aarti Holla-Maini took up the reins. Courtesy: UNOOSA

Six months after taking up the reins of the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), Aarti Holla-Maini is candid about the huge task she has taken on. She admits that she did not believe the warning of her predecessor, Simonetta Di Pippo, until she arrived at an office that had been without a leader for 18 months.

The biggest challenges Holla-Maini faces lie in the very system her office is part of, the United Nations, and a lack of resources. Specialised agencies such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) have a lot of freedom to choose who they can partner with or take money from. UNOOSA, by contrast, is much more constrained by the legal and ethical standards that maintain the integrity of the UN. These strict standards mean there is often trepidation at the idea of doing things in a new way, without precedents and where the boundaries of what is acceptable are grey. Holla-Maini has learned: “It’s a matter of diplomacy, of picking your moments. Doing something only when it’s necessary and not overstepping your boundaries.”

Money, or a lack of it, is another big hurdle for her ambitious plans for UNOOSA. In the next two years she wants to expand her office of 35 people to 100. This seems obvious to Holla-Maini, given that UNOOSA’s remit has grown from merely being a secretariat, at its establishment in 1957, to one of capacity building. Supporting member states to enable and leverage space technologies now takes up half the office’s capacity. It is involved in training people across nations to understand how to interpret satellite data, and has even helped turn non-spacefaring nations, such as Kenya, into spacefaring ones.

Is it time for a new Outer Space Treaty?

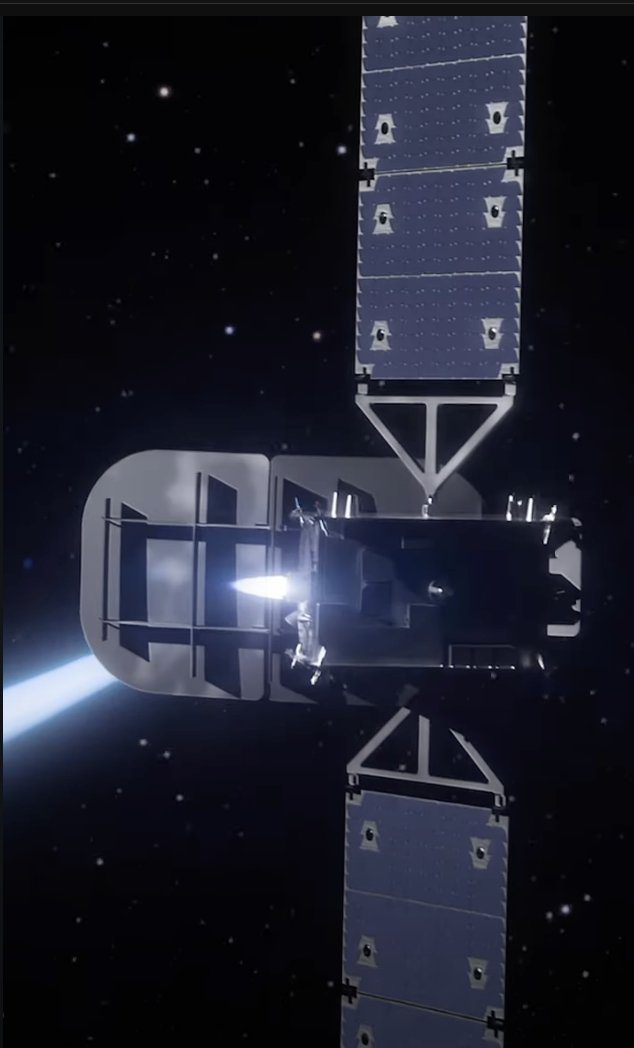

The UN’s influence on international space policy is immense. The agency is responsible for five treaties that underpin space law globally. These treaties are overseen by the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), for which UNOOSA provides the secretariat. In recent years questions have been raised about whether such treaties, including the Outer Space Treaty, some 56-years-old, need updating or if entirely new ones would serve global space affairs better.

For Holla-Maini, the answer is simple: “No, I would never suggest that we should open a treaty and start renegotiating it.” The space economy is built on the foundations provided by the existing treaties, along with the resolutions and guidelines born of the COPUOS process, she explains. There is also a pragmatic element to consider: “It’s naïve to think that we would achieve a new treaty in any realistic timeframe, given the current geopolitical situation.”

Instead, her focus is on guidelines. Since these are non-binding they lack the power of regulations stipulated in treaties, yet Holla-Maini is a passionate defender of them. Initiatives such as the Long-Term Sustainability Guidelines, adopted in 2019, are “the treaty of our times”, she argues. They took as long as any treaty to negotiate and involved many states from the start to the end, she adds. Crucially, they can be updated and are therefore more flexible, “whereas, had they been a treaty, which was then adopted and signed, the topic would no longer be on the agenda, and the treaty would then just be waiting for member states to ratify it”.

Even though it did not have a hand in either the US Artemis Accords or China’s International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) plans, her office is keen to encourage such examples of co-operation between countries. The first UN conference on sustainable lunar activities, organised by UNOOSA, is planned for this summer. Holla-Maini is encouraged by the ties that bind countries closer when it comes to space. Member states may not like each other’s politics and they even may be at odds, geopolitically speaking, but they do all want to be able to carry out safe and sustainable operations in space. “If I’m landing on the moon, whether I like your politics or not, whether I’m bigger than you or not, I certainly don’t want to crash with you.”

Countries also hold a secret power that Holla-Maini wants them to realise. They’re in charge of giving licences, enabling market access to different companies and deciding whether or not to share astronomical ephemeris and manoeuvre data with operators. “The minute you start putting holes into business plans, you’re talking about money, and money talks,” she says. After all, the last thing that any operator wants is to see is holes in its business plan by virtue of market access being denied by a country.

Courtesy: UNOOSA

UNOOSA and the ITU: a perfect match?

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the agency covering information and communication technologies within the UN, has “important and related mandates”, according to Holla-Maini. As a former satellite communications lobbyist, she has close ties and relationships with the ITU and its personnel and is eager to explore what the two could do together. She particularly sees an opportunity in regulation: “Regulators want to regulate – but they don’t necessarily know what to do because they are not space experts on the different aspects of space sustainability.” Her goal would be to ensure that “guidelines don’t remain just guidelines, but they do turn into regulations, implemented by regulators, space agencies, or governments at national level”.

The trouble with tracking everything going into space

For 62 years the UN has tracked all manner of objects, from satellites, probes and landers to crewed spacecraft, that have been launched into Earth orbit or beyond. The Register of Objects Launched into Outer Space became a treaty obligation in 1976 and is, among other things, used to help clarify which country bears responsibility and liability for objects in space. Its data has revealed that 2,664 objects were launched into space in 2023. That is the most objects in any year since the start of the register.

However, there are perhaps more still unaccounted for, as evidenced by a disclaimer on the UNOOSA website that around 86 per cent of all space objects have been officially registered with the Secretary-General, leaving one to wonder about the remaining 14 per cent. Holla-Maini explains that there have been instances where countries simply were not aware of their responsibility to inform UNOOSA: “that’s often when it’s a country new to spacefaring that has just become a spacefaring nation, and they didn’t know this responsibility, and this obligation, existed.”

The question of whether countries deliberately choose not to inform UNOOSA, for their own purposes, is a trickier one. Holla-Maini admits that sometimes her office is informed late but asserts that “the Treaty obligation, if I’m not mistaken, applies to all objects launched regardless of what purpose they are for”. Indeed, the resolution defines a “space object” as inclusive of component parts, as well as its launch vehicle and parts.

The topic of how UNOOSA, an office created to promote global cooperation in the peaceful use of space, handles countries embroiled in military conflicts is a difficult one in the light of geopolitical tensions between the likes of Russia and Ukraine, and Israel and Gaza. Holla-Maini is grateful that her office is not responsible for those negotiations, which reside with the Office of Disarmament Affairs based in Geneva. She does acknowledge, however, that there are some overlaps “because space-based technologies are very often dual use, both satcoms and earth observation”.

On travelling to the Moon

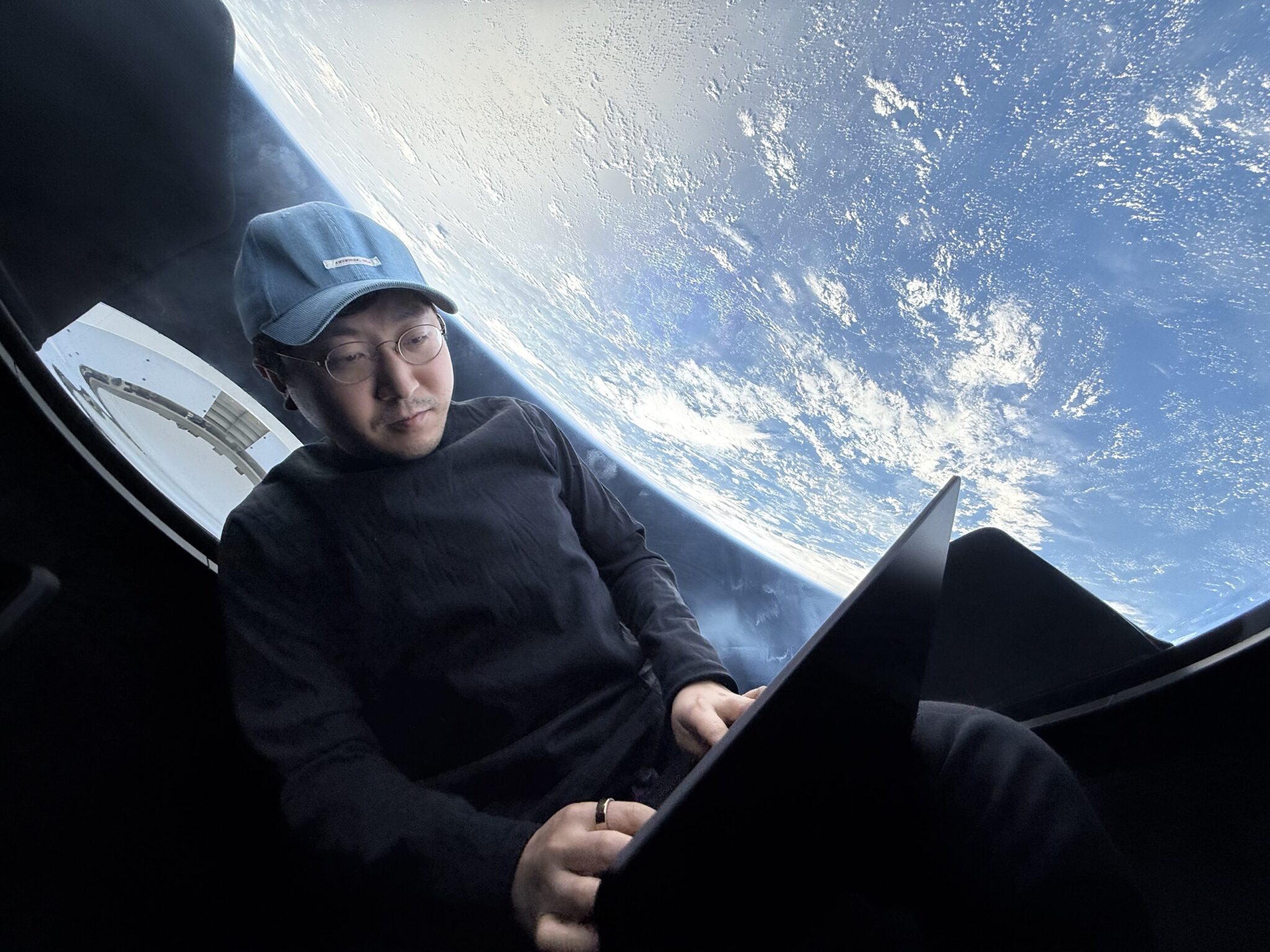

As the head of all things space at the UN, it might seem natural for Holla-Maini to harbour a desire, held by many others, to go to the Moon if offered the chance. However, having spent over 25 years working in the space industry, she confesses that she is not a fan of “all this space tourism stuff”.

She is aware of the inspiration that space missions, such as India’s Chandrayaan landing, provide for people. However, she is more interested in the benefits space holds for the masses on this planet. “Really”, she says, “the burning need is on Earth.” Staunchly, she tells me that “the true value of technology advancement lies in the benefits it brings to society as a whole”.

Holla-Maini points to the UN’s Space-based Information for Disaster and Emergency Response (more often referred to as SPIDER), managed by a team of around five people in UNOOSA, as an example. Everything from floods, forest fires, droughts and tsunamis to issues affecting health, such as mosquito-borne diseases and locusts, was discussed at the most recent SPIDER conference. For Holla-Maini it was a reminder of the many important practical needs for space data, and of UNOOSA’s key role in the dissemination of it.

So, as to whether she would go to the Moon, it is apparent that Holla-Maini would rather spend her time and her agency’s money on more urgent things, with growing UNOOSA at the top of her list.