The cost of NASA’s Mars Sample Return project has doubled from a projected US$5.3 billion to US$11 billion, prompting many to question whether it is worth continuing with the mission. In response, the US space agency has turned to its field centres for cost cutting ideas, with any mission delayed until 2035 at the earliest.

If this cannot be done (the life of the Perseverance rover, already on Mars, is an issue), then it seems likely that the mission will be cancelled and the money channelled into other NASA programmes, most probably the human lunar and Mars landing and return efforts.

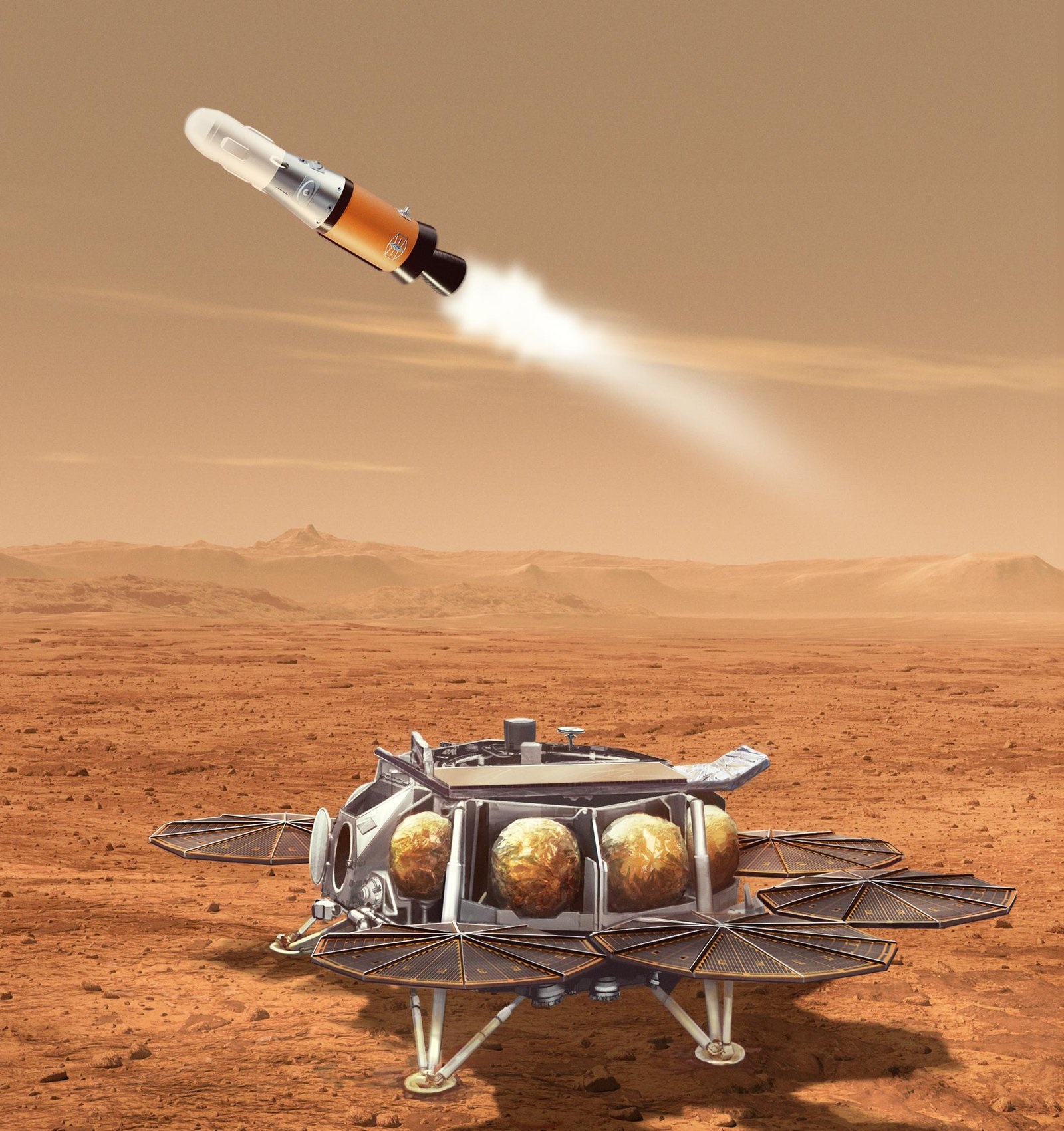

Artist’s impression showing Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) lifting off from lander carrying sample for return to Earth. Courtesy: NASA-JPL

The original plan

Although samples from the surface of asteroids, comets and the Moon have been brought to Earth, humans are yet to retrieve any from a planet. It was this missing piece that prompted the decision to attempt a remotely controlled sample return mission from the surface of Mars.

NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) combined efforts to create a plan to recover samples drilled from the Martian surface by Perseverance, the rover already on the planet. The original plan had a Mars return vehicle – the Earth Return Orbiter (ERO) – orbiting the planet and a landing craft – the Entry, Descent and Landing system (EDL) – that would attempt to land in the early 2030s.

After reaching the surface, the lander would receive samples from Perseverance via another ‘Fetch Rover’ and these would be placed in a 2.7 m long two-stage rocket dubbed the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV), being developed under a NASA contract by Lockheed Martin. This would lift off, taking the rock and soil samples back into Mars orbit.

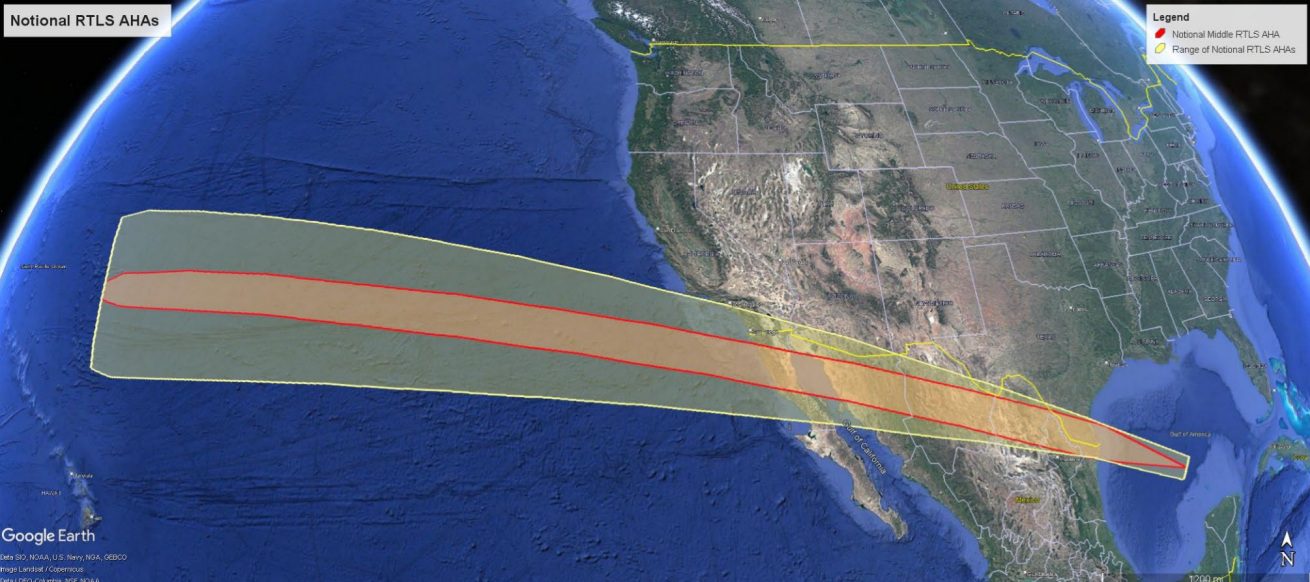

The ‘Orbiting Sample’ would then be picked up by the ERO return craft (finding it by its radio beacon) and placed into another sealed capsule before beginning its return to Earth. Just before its arrival, the ERO would release the capsule so it could make a direct entry into Earth’s atmosphere, followed by a parachute arrested landing in a desert. If all went to plan, the capsule, still hermetically sealed, would be taken to a laboratory for its contents to be released and examined.

What went wrong?

The original cost estimate for the Mars Sample Return project was US$5.3 billion before it rose to a projected US$8 billion and, finally, to US$11 billion – with US$3 billion already spent. An independent review, responsible for calculating the latest estimate, noted a series of missteps. These included an under-appreciation of the technology and timeline required for such a mission. The architecture suffered from excessive complexity, including five different types of spacecraft/rover vehicles and a convoluted rendezvous and docking procedure. Finally, and most importantly, the review found that general mismanagement of the project involved several field centres within NASA.

Apart from the cost and complexity, a separate concern about the mission has been voiced by scientists. Biological threats to Earth have long been a staple of science fiction, but they have been underlined more recently in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Mars sample return mission could expose our planet to such a threat through a potential breach of the sample capsule during the landing process, or due to a less than adequate quarantine system. Such fears have some justification: a parachute failure led to the crash landing and a breach of the Genesis capsule carrying solar wind particles back to Earth.

Suggested next steps

With the project in financial trouble, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson has asked the agency’s various field centres to come up with a cheaper plan. One option is to reduce the sample size to about a third of the planned amount, so a smaller and less complex lander and ascent system could be used. Another is to do away with the sample return aspect altogether and replace it with a specialist laboratory lander to conduct in-situ analysis of samples from the surface of Mars.

Comment by David Todd

The Mars Sample Return mission, attractive as it seems, is now so prohibitively expensive and its delays so pronounced that it should be scrapped, and its funding spent elsewhere.

For example, only a small portion of the billions of dollars saved would be needed to salvage the venerated Chandra X-ray observatory. It has a few years of observations left in it, if allowed to survive. On a grander scale, such was the success on Mars of the small robotic helicopter Ingenuity that NASA plans to fly one called Dragonfly on Saturn’s Moon, Titan. The agency needs more funding for these as projected costs have ballooned to over US$3.3 billion.

Similarly, if NASA wants to get to the Moon before the end of the decade, it needs to direct some cash to develop a small human-carrying lunar lander with storable propellants and a transfer stage for the early Artemis landing missions. The cryogenic efforts of SpaceX and Blue Origin for the planned Human Landing System (HLS) simply won’t be ready in time.

Finally, some of the savings should be used to start designing a human Mars mission, which could be flown by the late 2030s if NASA gets its act in gear. Such a mission would make any Mars robotic sample return mission redundant.