Ariane 6, Europe’s new rocket, has finally been launched from Kourou, French Guiana. The journey to this milestone has been far from smooth. The launch vehicle has been the target of much criticism aimed at its extended development time, its ‘out of date’ non-reusable technology and its exorbitant launch cost.

So, initially at least, some relief was felt as the ignited rocket lifted off at 1901 GMT on 9 July, clearing the tower upwards into the cloud-punctuated blue skies over the South Atlantic coastline. The French Air Force, renamed the Armée de l’Air et de l’Espace, even mounted a Rafale fighter chase plane to follow the rocket upwards on its climb.

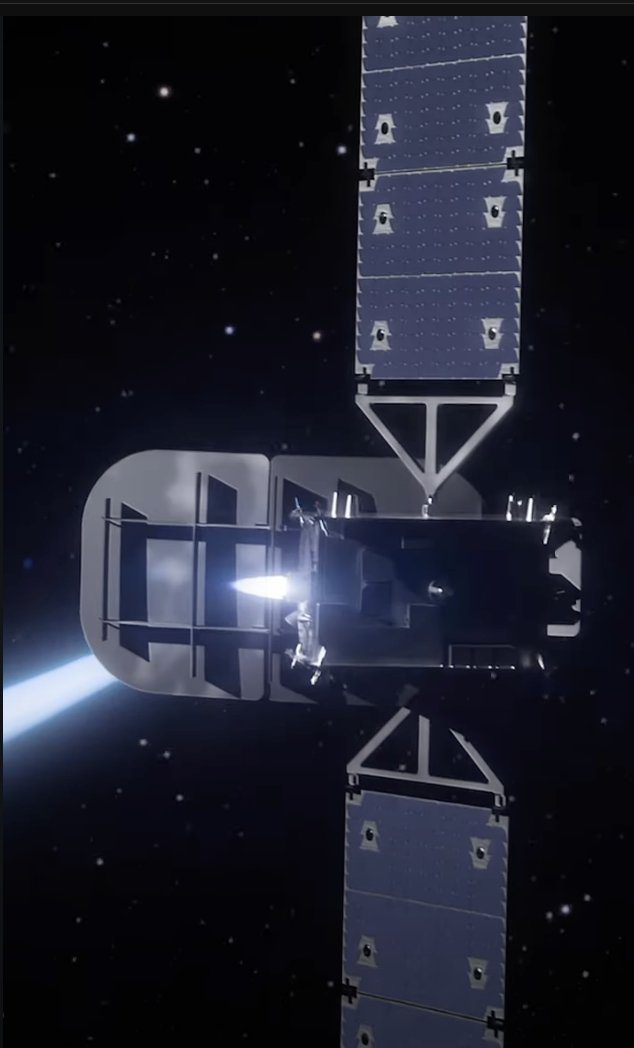

Ariane 6 maiden flight lift-off showing the bright glow of its Solid Rocket Booster’s efflux. Courtesy: Arianespace

The flight went as planned with the P120C solid rocket boosters (SRB) separation occurring at two minutes 16 seconds after launch, followed by a shutdown of the main liquid hydrogen/LOX core stage Vulcain 2.1 engine at seven minutes 35 seconds. After separation of the main stage, the upper stage was then fired for the first of three burns, with most of the spacecraft released after the second burn.

The Ariane 6 maiden flight streaks into orbit – followed for part of its climb by a French Air Force Rafale fighter jet. Courtesy: Armée de l’Air et de l’Espace

Aboard were 11 payloads. The largest was an instrumented mass simulator: a dummy designed to measure the accelerations and vibrations that a typical large satellite would experience on a standard flight. Attached to this were a number of hosted payloads: YPSat, Peregrinus, PariSat, SIDLOC, LiFi.

The other spacecraft payloads were much smaller:

- 3Cat4, a Spanish technology demonstration 1U Cubesat, aiming to demonstrate the capabilities of nano-satellites for Earth Observation (EO) using a Global Navigation Satellite System – Reflectometry (GNSS-R) and L – band microwave radiometry, as well as for Automatic Identification Services (AIS);

- Curie A and B, two 5 kg US spacecraft designed to study radio burst emissions from solar eruptive events;

- Curiumone (Major Tom), a technology demonstration microsatellite;

- GRBBeta, a 2U Cubesat with a primary mission of detecting and studying gamma-ray bursts and similar high-energy events;

- ISTSat-1, an ADS-B equipped technology demonstration 1U Cubesat for aircraft tracking;

- OOV-CUBE, a 10 kg IoT (Internet-of-Things) technology demonstration communications satellite for agricultural use;

- Replicator, a 5 kg spacecraft to demonstrate 3D-printing in orbit;

- ROBUSTA-3A, a 3U Cubesat from the University of Montpellier to test GNSS reflectometry techniques for mapping atmospheric water vapour.

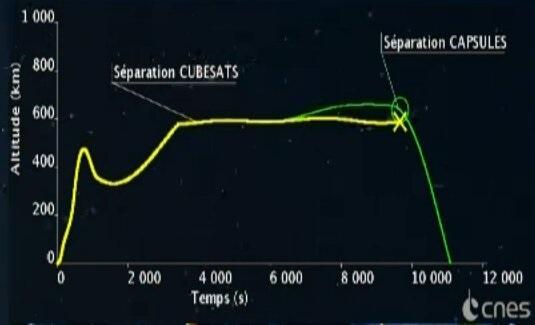

Tracking data soon showed an altitude shortfall at the end of the flight. Courtesy: CNES

The Ariane 6 maiden flight delivered all nine of the payloads listed above to their correct orbits but an anomaly prevented it from doing the same for Bikini Demo (NYX) and SpaceCase SC-X01 re-entry test payloads. An APU (Auxilliary Propulsion Unit) failure on the upper stage ignited but only briefly, preventing the third ignition of the Vinci engine. Control immediately decided to passivate the upper stage to prevent the risk of an explosion. This means that the upper stage, with the satellites still attached, will have an uncontrolled re-entry – although it will be some years before this happens given its altitude.

A closer look at Ariane’s APU

Prior to the flight, analysts had noted that if a failure was to occur, it was most likely to be related to the rocket’s APU. This is because it was utilising new technology which represented the one major difference between the Ariane 6 and its predecessor Ariane 5. The technology was introduced to pressurise the tanks for multiple reignitions of the cryogenic expander-cycle Vinci engine (the Vinci’s HM-7B cryogenic gas-generator cycle predecessor was not restartable). The APU achieves this by drawing a small quantity of liquid oxygen and hydrogen from the tanks and heating them up using a gas generator. The heated and pressurised propellant is then injected back into the tanks. Exhaust from the gas generator burns also has an ‘ullage’ function to accelerate the upper stage slightly to settle its propellants towards the bottom of the tanks, ensuring optimal operation of the Vinci engine’s turbopumps.

Comment by David Todd: Arianespace can be congratulated for a mostly successful flight. However, Slingshot Aerospace’s Seradata database team does regard this launch as a partial failure – albeit a minor one. We judge all launches in the following way: if even a single payload on a launch does not achieve its correct orbit in an undamaged condition, the launch is classed as a ‘raw total failure’. However, we then modify this by taking into account how many payloads onboard did achieve their correct orbits.

For the unsuccessful ones, we make an estimation of the remaining life or capacity, and accordingly annotate the failure using a ‘capability lost’ function. For example, a spacecraft may be able to recover itself using onboard propellant (at some cost to its lifespan). This would result in a ‘spacecraft capability loss’ of 50 per cent. After summing up, we will come up with a figure of the percentage failure of the launch. In Ariane 6’s case, two of the 11 spacecraft failed to achieve their orbital drop-off in a non-recoverable way. Thus, the Ariane 6 maiden launch is regarded as an 82 per cent success.