At the 35th Space Symposium in Colorado on 9 April, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine put some meat on the bare bones of a plan to return humans to the Moon by 2024 – a challenge made last month by Vice President Mike Pence and accepted by Bridenstine on behalf of NASA. To put NASA astronauts onto the Moon as soon as possible, Bridenstine has accepted that the development and construction of a lunar landing module and separate ascent craft should be prioritised, ahead of the completion of longer-term elements for lunar exploration including the Lunar Gateway orbiting space station.

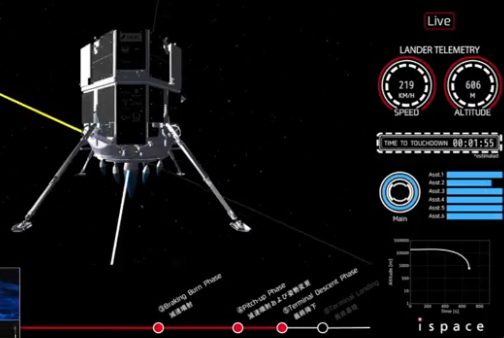

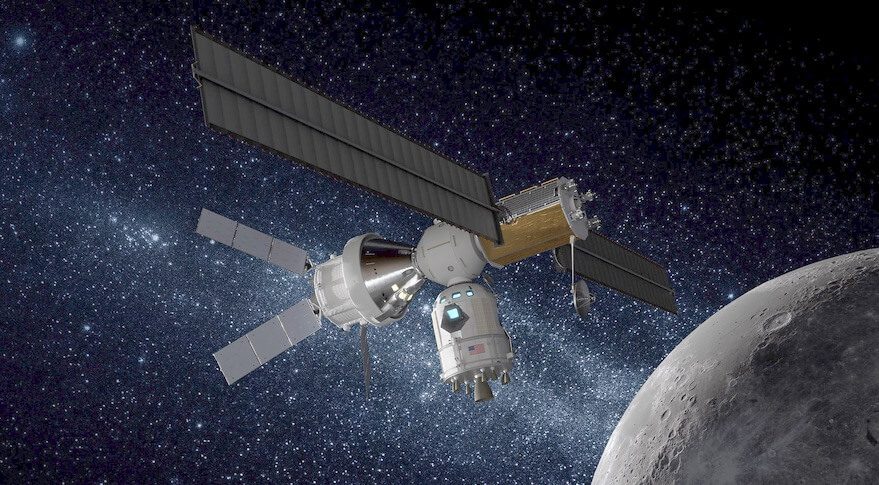

Lockheed Martin’s suggestion for a cut down Lunar Gateway and lunar landing/ascent craft. Courtesy: Lockheed Martin

Nevertheless, the construction of the Lunar Gateway will have been started and may still have a role in these landings. For example, Lockheed Martin has suggested that a cut down version of the Lunar Gateway should be built to accelerate the lunar landing element of the programme, and that the first crewed mission of Orion EM-2 should actually dock with this mini-space station. Later, two separately launched landing and ascent stages for a lunar landing module would be deployed at the station so that landings can be attempted.

However, critics of the Lunar Gateway plan are pressing for a more directly launched lunar landing mission. These include the influential space writer and mission designer Robert Zubrin who is part of a team promoting their Moon Direct idea.

Either way, Bridenstine confirmed that human lunar lander, ascent and tranfer stages will be developed and built via public-private partnerships. These will initially cover the design phase of the Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) programme, which is now being expanded to include an ascent module in addition to landing and transfer elements. The lunar South Pole is the target of the initial exploration.

Bridenstine reaffirmed that the delayed SLS (Space Launch System) heavy lift rocket would still have an important role, even if its later more powerful versions have effectively been cancelled. “First, we are focused on speed to land the next man, and first woman, on the Moon by 2024. Second, we will establish sustainable missions by 2028. To do that, we need our powerful Space Launch System to put the mass of reusable systems into deep space,” he explained.

The initial launches of SLS Block I will include the EM-1 unmanned test of the Orion craft on a trans-lunar mission in 2020, which would be followed by a crewed mission.

As Bridenstine announced prioritisation of the construction of a lunar lander and ascent module, NASA also reported an addition to his staff. Mark Sirangelo, former CEO of Sierra Nevada – the firm developing the Dreamchaser mini-shuttle – has been hired as Special Assistant to the Administrator. His job will be to develop the strategy to meet the Administration’s policy to return astronauts to the lunar surface by 2024.

Comment by David Todd: The cut-down lunar gateway model is a runner and does provide astronauts with a “place of safety” in lunar orbit should any lunar-Earth transfer not be possible. However, a quicker route would be not to use the Gateway at all, and to opt instead for an independent two-launch architecture. This could employ a Falcon Heavy (with an ICPS upper stage) – a combination rocket recently mooted by Bridenstine – to launch a lander/ascent module on a transfer orbit to the Moon. The lunar lander/ascent module would have to use its engine to brake itself into lunar orbit first. A day or so later, a human-rated SLS Block I rocket would send the Orion spacecraft (plus service module) and four crew towards the Moon. It would similarly brake into lunar orbit, make a docking with the lunar lander. The crewed landing would then take place, followed by an ascent, a redocking with Orion and then a return to Earth. Such an architecture could also use pre-launched lunar surface shelters as “places of safety” like NASA’s pre-Apollo Project Pilgrim idea, and, more recently, Robert Zubrin’s Moon Direct plan.

This dual-launch plan is only possible if a Falcon Heavy/ICPS is used as well as SLS because NASA leased its Shuttle/Saturn V pad LC-39A to SpaceX, and thus cannot itself quickly launch two SLS from adjacent pads.

By the way, a back of an envelope calculation is that a Falcon Heavy launched in expendable mode with an ICPS fitted as a “third” stage, would be able to put about 25 metric tons or so into a TLI (Trans Lunar Injection) orbit – about the same as an SLS Block I. So, any lunar landing/lunar ascent craft would have to make that mass. The Apollo Lunar Excursion Module weighed in at circa 16 metric tons, but it did not have to brake itself into lunar orbit. Carrying fuel to do this would add perhaps another ton or two. In short, this very basic lunar excursion mission would be possible.

A larger (and heavier) module would be needed to carry three crew to the lunar surface, and even more if it were to be reusable. As such, we recommend extending the ICPS stage – a relatively inexpensive and quick-to-do move – which should allow a TLI capability of up to 35 metric tons using either the SLS or Falcon Heavy.