While staging in rocketry has been around since the 1940s, culminating in the first orbital success with Vostok rocket’s flight of Sputnik 1, stages were not truly reusable until the arrival of the Space Shuttle in 1981. Even then, one major part of its stack – the Shuttle’s external tank – was destroyed. NASA eventually gave up on refilling the notionally reusable solid rocket boosters (SRB) once it realised how uneconomical refurbishment was. Even reusing the main orbiter proved expensive due to its interflight maintenance and safety checks, which meant that launches by the Space Shuttle were about ten times as costly as those by an expendable. However, as Elon Musk and SpaceX were planning another test flight of the Starship/Super Heavy combination in February 2024 – hopefully third time lucky – that ‘Holy Grail’ of complete, and economic, reusability may be achieved.

The concept of multi-stage reusability goes back to aircraft with the Short-Mayo Composite concept in the 1930s. Up to that point, engine and aircraft technology meant that there was no way of getting a heavier-than-air aircraft all the way across the Atlantic – a distance of around 3,200 miles – without the normal re-fuelling stops in Newfoundland, Greenland and Iceland. The state of technology at the time meant that if an aircraft/flying boat had enough fuel to make this trip, and enough cargo to make it worthwhile, its engine power/wing combination could not get it off the ground.

However, the technical manager of Imperial Airways (which became BOAC), Major Robert Mayo, worked out that such an aircraft would be able to fly across the Atlantic if it could get airborne, but that it might need a second aircraft to get it there. So he suggested that, if a Short Brothers S.21 Maia “first stage” large flying boat could be used to carry a fully fuelled S.20 Mercury sea plane up to the correct altitude, the Mercury “second stage” could be released/separated to safely fly across the Atlantic. The Maia flying boat would then return to base or to a nearby destination.

Reusable staging in the 1930s: postcard of Short-Mayo composite. Courtesy: Valentine’s Postcards

And it worked – with a few BOAC-operated slow long-range demonstration flights (it took over 20 hours to cross the Atlantic at a cruise speed of about 160 mph) being used to deliver mail and passengers to Canada and South Africa in 1938 and 1939. But its career was short-lived as the Short Mayo Composite was superseded a year later when PanAm (and later BOAC) and American Export Airlines started operating regular non-stop transatlantic services using individual large Boeing 314 Clipper and Sikorsky VS-44 flying boats, respectively – a hint that single-stage operations are usually economically superior. These flying boat trans-Atlantic flights carried on during World War II, and even Winston Churchill used them. The same was not true for the only Short Mayo composite (only one was built) which was destroyed in 1941 by a German bombing raid.

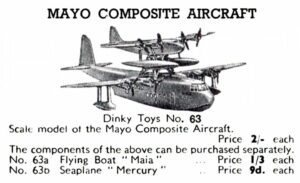

Catalogue image of the Dinky model of the Short-Mayo Composite. Courtesy: Dinky via www.brightontoymuseum.co.uk

By the end of the war, single land-based aircraft such as the Douglas DC-6 and Lockheed Constellation were also able to make non-stop transatlantic crossings, usurping all flying boats as they did so. While it has just a short listing in aerospace history, the multi-reusable stage Short Mayo Composite concept was at least technically proven during the short period that it flew. And it became a popular Dinky toy model.

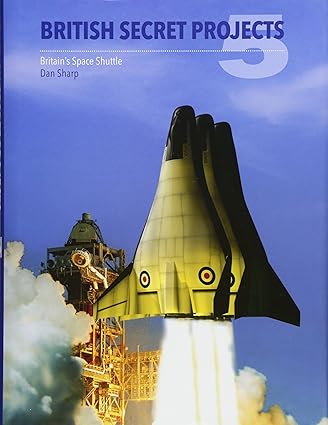

Project Mustard concept. Courtesy: British Secret Projects.

Back to rockets. While staged expendable rockets worked successfully, the manufacturing cost for a single flight remained expensive, and it soon became apparent that reusability should be tried. Several concepts were worked on – on both sides of the Atlantic. During the 1960s, the UK dabbled with a concept called Project Mustard, consisting of three lifting body stages, all reusable, but it was never developed. By the 1980s, the UK eschewed multi-stage reusables and began to consider the HOTOL and later Skylon single-stage-to-orbit designs using air-breathing rockets. However, the development costs and a lack of interest by the UK government at the time meant that neither of these reached fruition – mainly due to the government’s reluctance to risk large-scale investment on the untested concept.

Boeing reusable three-stage rocket concept. Courtesy: Boeing

In the US, NASA went down the route of a two-stage winged system for its Space Shuttle. However, in the end a combination of development cost, and a lack of technological readiness, meant that its final design was only partially reusable and that its main external tank was expended. As already noted, the Space Shuttle was more expensive to operate than a conventional expendable launch vehicle.

Original “both stages reusable” concept for the Space Shuttle on show at the Smithsonian. Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

As the Space Shuttle neared retirement, Boeing briefly considered a three-stage reusable design (it is still working on its XS-1 part-reusable concept for DARPA). But that went the same way as the US’s brief dalliance with a single-stage spaceplane called NASP and a later Lockheed X-33 single-stage aerospike engine powered design, neither of which were technologically ready. Nevertheless, there was progress – and it did not involve wings.

The DC-X test programme proved that large rocket stages could be launched and landed propulsively and safely. SpaceX (and later Jeff Bezos) took this idea and used it to create part-reusable rockets, such as the Falcon 9/Falcon Heavy and the yet-to-fly New Glenn series. These have reusable first stages that can land either down range or even close to the launch site. The Falcon 9 series has worked well and has proved that part-reusable rockets can be operated more economically than equivalent expendable launch vehicles, provided minimal maintenance is needed between each flight.

But that was not enough for Elon Musk. After briefly considering developing a reusable upper stage for Falcon 9, Musk decided to build a completely new design using LOX/Liquid Methane as propellants, with the idea that this might one day be used to reach Mars. And so, the Starship/Super Heavy combination was born, and that is what we are looking forward to. Made of stainless steel, thus requiring little extra thermal insulation, it is hoped that this new radical upper stage may survive re-entry – the difficult part – and be able to land back on Earth intact. If Musk and SpaceX succeed in this, it really will rewrite aerospace history and yield launch prices about one tenth of what they are today.

Starship IFT-2 launch immediately after the hot separation of the stages. Courtesy: SpaceX