Rockets have carried humans around the world, mainly in low Earth orbits (LEO), and even, on occasion, to the Moon and back. Yet orbits over the polar regions of the Earth remained unexplored by peopled spacecraft. That was until April when SpaceX launched Fram-2, the first crewed mission to conduct an orbital flight over the polar regions of the Earth.

Four commercial astronauts were on board the Crew Dragon Resilience spacecraft when it was launched on a Falcon 9v1.2FT Block 5 from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida, US on 1 April at 0246 GMT.

Crew Dragon Fram-2 mission lifts off on a Falcon 9. Courtesy: SpaceX

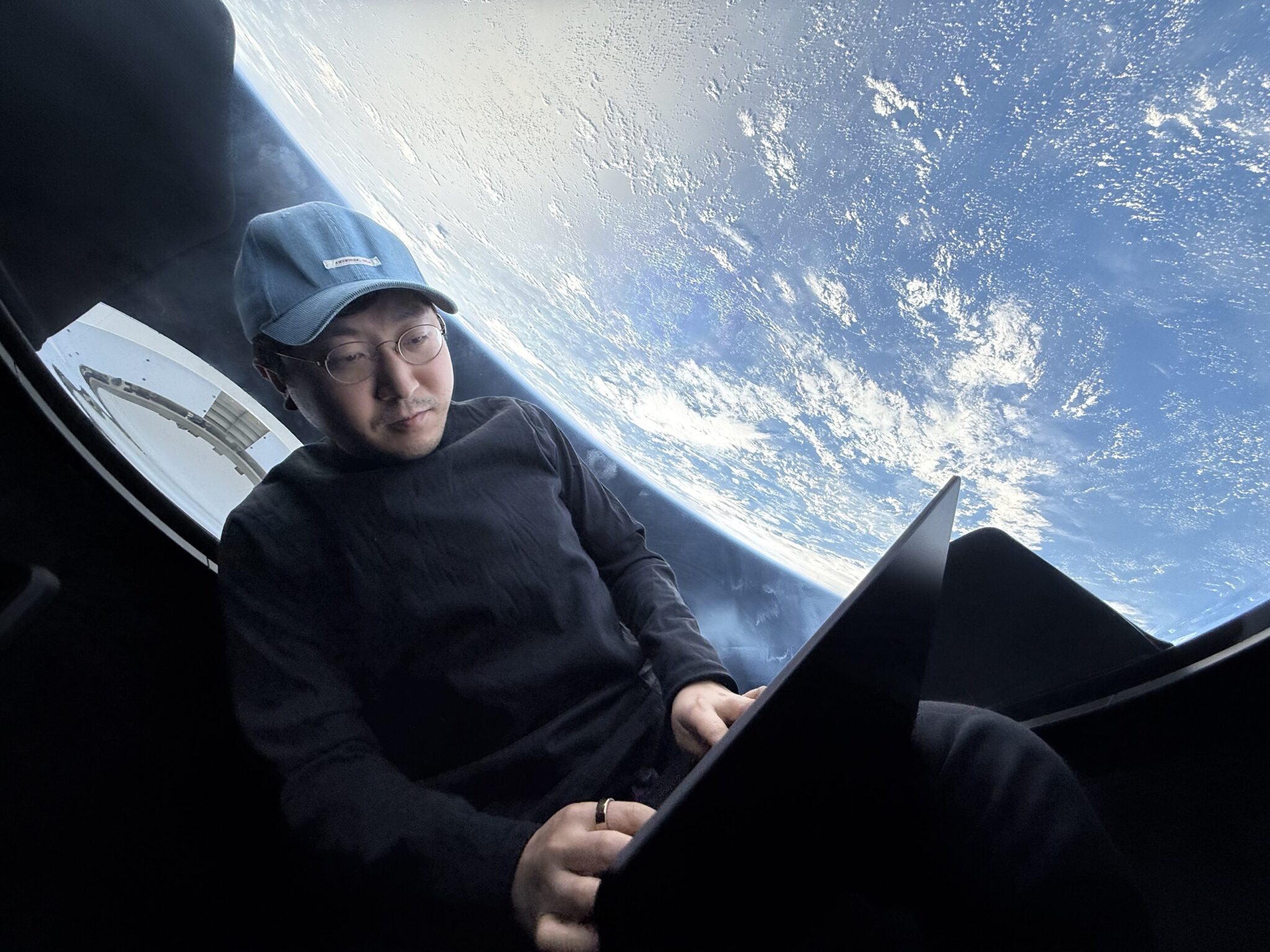

Antarctica as imaged by Chun Wang on the Fram-2 polar orbit mission. Courtesy: Fram-2/Chun Wang

Fram-2 mission details

The Fram-2 mission – named after the former Norwegian Arctic/Antarctic exploration ship Fram (meaning ‘Forward’) – was funded by Chinese-born Maltese tech investor Chun Wang, who was also the mission commander. His three crewmates were Yannicke Mikkelsen, Eric Philips and Rabea Rogge.

The mission was due to last about four days and to fly at an altitude of 430 km at 90 degrees inclination. The launch took a southerly trajectory into a polar orbit (the initial orbit achieved was 431 x 202 km at 90.01 degrees inclination). The reusable B1085 first stage, on its sixth flight, landed on the drone ship A Shortfall of Gravitas down range.

Various scientific observations were made, among them an attempt to investigate polar aurorae phenomena such as the ribbon-like Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement (STEVE). Experiments also examined the effect of the orbit on the human body, including the first X-ray plate being taken in space.

Towards the end of the mission, the spacecraft made two orbit lowering burns on 3 April. It then made a re-entry burn and a parachute-slowed splashdown in the Pacific at 1619 GMT on 4 April, off the coast of California.

Chun Wang works on his computer in front of the cupola – a window dome attached ahead of the upper hatch. Courtesy: Fram-2/Chun Wang

Why human spaceflight has avoided polar orbits

The reason why human space exploration did not previously attempt to reach polar orbits can be summed up in one word: radiation. There is an element of danger from an increased radiation flux density because charged particles are funnelled down field lines at the poles.

The astronauts and Dragon capsule electronics were only in the danger zone for about a minute per orbit. However, given that the duration of the mission was four days, it amassed 60 passes through each polar region – 120 in total – amounting to about two hours of exposure. Non-polar LEO spacecraft must also go through similar South Atlantic Anomaly high-intensity radiation zones, but less frequently due to the Earth’s rotation and orbital precession.

A secondary reason is that polar orbits require more propellant because their launches do not benefit from the extra push provided by the Earth’s spin for eastward flying launches.

Another risk related to these regions is that of an unplanned landing in an uninhabited and extremely cold area should something go awry with the re-entry sequence. The danger is of not being able to reach or rescue the crew in time in such difficult conditions.

Crew Dragon – Fram 2 splashdown. Courtesy: SpaceX