When SpaceX first achieved the recovery of its Falcon 9 rocket’s first stage in late 2015 (admittedly after a few failed attempts), the world hailed it as a new step in spaceflight. However, the truth is that nothing practical for actual space operations was proven until such a recovered stage was successfully reused. SpaceX achieved this feat when its Falcon 9 1.2FT-RR (“RR” is Seradata’s nomenclature to indicate a “Reused Reusable” as SpaceX refuses to differentiate) successfully launched the SES-10 satellite into a geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). The launch took place at 2227 GMT on 30 March 2017 from its launch pad at the Kennedy Space Centre, next to Cape Canaveral in Florida.

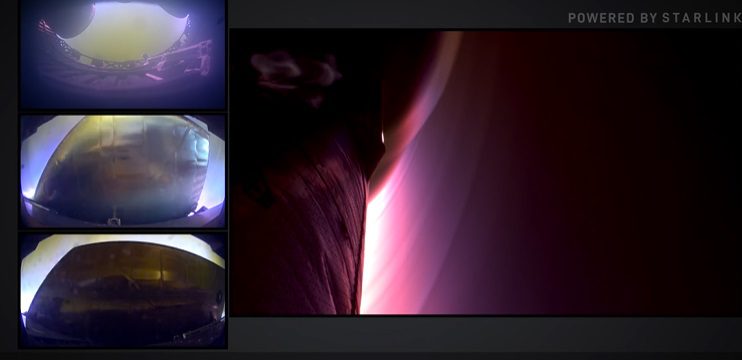

Eight and a half minutes later the stage was successfully landed on the ocean going barge “Of course I still love you” downrange. Elon Musk, founder of SpaceX, looked relieved and happy as he hailed the achievement of commercial reusability. Perhaps more importantly, the rocket’s second stage powered on to deliver its 5 metric ton SES-10 satellite payload into GTO, on its way to its final geostationary orbital position.

A happy Elon Musk said in a webcast after the flight: “I think it’s an amazing day for space.”

“It means you can fly and re-fly an orbit class booster, which is the most expensive part of the rocket. This is going to be, hopefully, a huge revolution in spaceflight.”

It has not been disclosed exactly how much refurbishment the stage needed before its flight, except to note that the core structure and engines were not changed. SpaceX does, however, admit to changing some higher risk “auxiliary” components after their heat load (e.g. the grid steering vanes, and some parts of the heat shielding), although in future it does not plan to do this as the parts will use more heat resistant materials (e.g. switching from aluminium to titanium for the steering vanes).

SpaceX is anxious to prove that there will be very few changes between each flight to make the economics of reusability work. For example, this was the financial Achilles’ heel of the Space Shuttle: the need to strip down its liquid propellant powered main engines, carefully refill and recheck its reusable solid rocket boosters, and make a detailed check and repair of the orbiter’s thermal protection tiles. This expensive and time-consuming refurbishment effectively made the Shuttle about three times more expensive to launch than a normal expendable rocket of similar lifting capacity.

By the way, it is the weight penalty of the required thermal protection system that is the reason why the Falcon 9’s upper stage, which re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere at a much higher velocity than the first stage, is not yet reusable.

Some space experts deride partially reusable rockets, noting that flight numbers have to increase dramatically before the technology makes economic sense. This was the European Space Agency’s thinking when in plumped for a low–cost expendable design for its new Ariane 6 launch vehicle.

Nevertheless, other launch vehicle experts predict that reusability will dramatically cut the cost of launches if ten or more flights can be made using the same hardware with little refurbishment between flights. So, in reality, there are nine more flights to go with this stage (or another reused stage) before a judgment can be reached.

The practicality of regular reusability might also be limited by the types of launch being made. For example, a flight to low Earth orbit is known to be a much more benign aero-thermodynamic re-entry environment for a first stage than one for a “high energy” GTO flight, which re-enters at a higher velocity and a much steeper angle.

While the financial details of this latest mission have not been released, SpaceX is reported to be offering an initial discount of 10% off its published US$62 million flight price for launches involving reused (which it amusing dubs “flight proven”) hardware. It expects this discount to increase with experience.