Whether you call it coronavirus or COVID-19 you cannot avoid this “Elephant in the Room”, which is affecting much of industry and commerce, the world’s health systems and even basic human relationships. And space has not been insulated from the virus. Despite a tardy response from certain governments, borders are now being shut, social isolation is being enforced and businesses have been shut down.

Coronavirus image looks very like Cavor’s sphere space ship with its train buffer projections in the 1964 film version of H.G. Wells story The First Men in the Moon. Its final scene aptly warns of the danger of viruses to civilisations. Courtesy: Columbia Pictures

The mistakes have been legion. They began with a cover-up by regional elements of China’s Communist regime, but have been followed by a reluctance to take decisive action by democratic governments, which made the mistake of trying to have their cake and eat it as they put their economies a little ahead of fighting the threat. The reluctant to close the beaches Mayor of Amity Island in the movie Jaws (1975) comes to mind.

In the USA, the Trump Administration originally ignored and then belittled the threat, hoping that it would go away. Meanwhile, in the UK, the Boris Johnson-led government, after failing to stop the initial seeding, briefly toyed with the idea of allowing “herd immunity” to be achieved before realising that the National Health Service (NHS) would not cope.

The result was that both governments delayed taking more draconian measures to help stem the spread of the disease – until heeding the warnings of virus scientists and epidemiologists as the infections grew. Some progress on reducing the rise in deaths is becoming evident in the UK since its soft, then hard “lock downs” on personal movement were announced. However, in the end, even His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales, and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson himself, became infected. As they started to suffer similar infection rises, some of the most populous US states have employed similar lock down strategies to the UK including California and the very badly affected New York State.

Other governments had to cope with their populations (especially in Italy and France) not taking warnings about the virus seriously enough as they carried on with their socially connected lives. Nor was the danger taken seriously enough by the younger generation in general. Having berated their forebears for global warming, inequality and the financial crash, they continued to gather irresponsibly on the coasts of the USA or at parties in London, with the result that bars and restaurants had to be forcibly shut.

As a result people are dying because of these mistakes. Thousands of much-loved older and health compromised people are now succumbing to the infection, with a bias towards male fatalities.

The Chinese government may have wasted weeks, but it did eventually manage to regain control by enforcing a draconian lock-down on personal movement in the affected regions. Other nations, including Singapore, South Korea and Japan, did even better by taking strong action. They were successful in tracking the connections of the infected and isolating them. But with the genie out of the bottle and the constant threat of reinfection from abroad, these and many other nations are planning to keep their borders more or less shut, with entry allowed only after a negative test for infection, until a vaccine is found. This will have major implications for world travel and trade – and yes globalisation – even after the main part of the crisis is over.

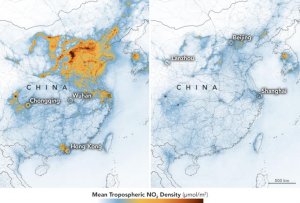

NASA satellite images note downturn in NOx pollution in China during Coronavirus outbreak. Courtesy: NASA

Those charting the spread of the virus, such as the statistics team at the Financial Times, showed how successful, or not, each nation had been in fighting the virus. Those nations doing well had employed lock-down measures early and managed to achieve a curving graph trajectory better than China’s.

In some places, however, the advance of the outbreak seemed to be uncontrollable with Spain, and increasingly the USA, starting to experience growth rates in infection and mortality worse than in Italy and China.

Nevertheless, with his electoral “Trump card” (pun intended), the US economy, now being damaged by movement restrictions, US President Donald Trump became keen to relax these, potentially making a very bad situation much worse. But in the end sense prevailed.

As the world’s less-developed nations such as India become infected, there are fears that they could be the worst hit of all. For while lock downs and other measures will slow the spread, possibly the best option will be to achieve herd immunity. This accepts that that the infection will spread, with the hope that this will be slow enough to allow these nations’ medical services to cope.

Arianespace Vega rocket carrying UAE Falcon Eye 2 spysat having its stages stacked…but its launch was indefinitely delayed. Courtesy: ESA/CNES/Arianespace/Photo Optique Video du CSG (P. Piron)

Even in nations with a state healthcare system with more than the average number of intensive care beds, Italy, and even France, found that hospitals were being overwhelmed by demands for medical help as more and more people succumbed to the virus.

Grimly, imaging satellites began to observe mass graves being dug in some countries (e.g. Iran). One minor bright spot was that some satellites also registered the downturn in pollution as economic activity ground to a halt.

As those traditional distractions, sports events and those refuges from the world, pubs, restaurants and cinemas, were shut down, central banks cut interest rates and governments began to deliver financial support to businesses and workers in a succession of bigger and bigger packages, via tax holidays and straight handouts. The idea of “helicopter money” – delivering cash directly to households – also took hold in some countries.

So how is all this affecting spaceflight?

First to be affected were the space industry’s round of conferences. Enforcement of rules banning mass gatherings came through too late to stop the Satellite 2020 conference in March, but attendances were markedly down. In the end, under pressure from Washington DC city authorities, the three-day conference was stopped one day early.

The next big event on the space conference circuit was the Space Symposium, which was to have been held in late March in Colorado Springs. This was cancelled (or rather delayed indefinitely) after US President Donald Trump, who finally woke up to the threat having previously played it down, noted that large gatherings were not a good idea and brought in a travel ban from Europe. European governments somewhat hypocritically protested at this border shutdown before imposing their own border controls. Other major events were cancelled elsewhere including the Farnborough International Airshow in England in July. Some exhibition and conference venues did find another use for themselves as they were soon converted into emergency hospitals.

Having shut US borders, President Trump tried to console the business community that cargo would still be allowed though. But for European satellites heading for a US launch site, travel was still impossible without their attending engineers. Manufacturing plants, their deliveries of “just in time” part supplies already affected by the virus, found that keeping most staff at home worked well for design engineers and business types using computers (including insurers at Lloyd’s of London), but not for the staff actually putting satellites together. For example, Maxar’s SSL division, located in California, warned clients that its satellites would be late.

In the end, even the launch providers who had been promising that launches would go ahead found themselves considering shutdowns. First to do so was Arianespace, then India’s space agency (ISRO), and more were expected to follow. Only China remained likely to keep up the tempo on the grounds that its lock-down measures had worked well enough for operations to continue.

While travel cancellation and medical insurance faced huge payouts (although some shrewd insurers only underwrote policies with exclusions for pandemics), space insurance as a class started to look less bad, especially since premium rates had risen after last year’s loss. But there was still a fly in the ointment. As commercial launches became delayed so were premium payments.

Even NASA has been affected. NASA Ames was the first field centre to shut because of an infection case, followed by NASA Marshall. While NASA HQ in Washington DC officially stayed open, most of its operatives began to work from home. In the end, it shut its centres to all but essential staff. Work on SLS and Orion was also suspended, further delaying the programme and adding to its cost. NASA began choosing which projects it had to keep staff to working on including suspending work on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The European Space Agency (ESA) was in a similar boat and even put some of its already launched long range space missions: the Cluster quartet, ExoMars TGO, Mars Express and Solar Orbiter, into Safe Mode “Hibernation” to limit the number of personnel it would need a its operations centre.

While world television sporting events were shut down – most notably the Olympics and most of the Formula 1 season, communications satellite companies still benefited in the short term because of the increased demand for capacity caused by more people working from home and those using more online leisure applications. Likewise there was also an increased demand for Earth imagery. But those providing aviation and maritime communications, such as Inmarsat, SES/O3b and Gogo (via Intelsat and SES), sadly saw clients in the cruise ship and airline industries rapidly curtailing operations.

Probably worst affected are the launch vehicle and satellite constellation start-ups, who are finding it almost impossible to raise finance in the current crisis. There were reports, for instance, that OneWeb had laid off staff because of financial difficulty. It later filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Struggling established space companies found that Coronavirus was the last straw including inflatable space station module specialist Bigelow Aerospace which promptly laid of its entire workforce.

Some investors in these ventures may have wondered whether they should have put money into companies making toilet paper, pasta and tinned fruit instead. As the empty supermarket shelves show, these continue to be popular at times of duress.