At the Farnborough International Air Show, Space technology was in evidence – most noticeably the special Space Zone in Exhibition Hall 3 where UK and other countries had their space wares on display. There were also some big announcements. The UK Government along with the UK Space Agency announced that eight locations had been selected as finalists as the location for Britain’s first “spaceport”.

Standing in for the departed Minister for Universities and Science, David Willetts, was Robert Goodwill MP, Under Secretary of State for Transport, who noted that it had been decided early on in the process an existing aerodrome with a runway at least 3000m long should be chosen instead of building on a “greenfield site”. The spaceport should be well connected by transport links but be away from air traffic hotspots. It should also be ideally near the sea and away from populous areas, while also having a low noise and environmental impact. In addition, good weather with low cross winds would be an advantage.

The finalists that made “the cut” included: Stornoway Airport (Isle of Stornoway, Scotland), RAF Lossiemouth (Scotland), Kinloss Barracks (Scotland), RAF Leuchars (Scotland), Cambeltown Airport (Scotland) Prestwick Airport (Scotland), Llandedr Airport (Wales) and Newquay Airport, (Cornwall, England). It was suggested in jest that given most of the planned locations were in Scotland it might be a way of encouraging Scotland to vote to stay in the UK in September’s referendum. Once the final selection has been made it is envisaged that the spaceport will be built by 2018.

While some uninformed media reports suggest that the candidate sites might one day be used for orbital space planes, this is only partially correct. While most of the candidate UK spaceport sites would be suitable for launches to high inclination polar and sun-synchronous orbits – a popular orbit type used by Earth observation spacecraft and some communication satellite constellations, none of the finalist spaceport sites is ideal for lower inclination orbit spaceflight used for flights to the International Space Station and flight to Geostationary Earth Orbit, both of which would normally require an Eastward passage. This is because dropping rocket stages on populous areas of Europe is officially frowned upon – not least because under international law on space liability, the UK would be the “launching state” and would thus be liable for any injuries or damage caused by falling rocket stages.

In fact, the UK mid-Atlantic territory of Ascension Island would have been a better choice in this respect allowing both Eastward and Polar launches without hindrance. However, the aptly named Ascension Island fell out of the running at an early stage, presumably due to its remoteness and lack of transport links. Given that the early users of the spaceport would be mainly suborbital launch operators, and perhaps their air-launched orbital cousins, the thinking of the Civil Aviation Authority is that a UK-based airstrip site would be best. Should it ever be needed, a second launch site could be set up, possibly concentrating on vertically-launched and vertically landed launch vehicles.

Getting expert advice from the US FAA

As part of its preparations into allowing commercial spaceflight operations to begin in the UK, there was a signing of a Memorandum of Cooperation at the Farnborough air show between the US Federal Aviation Administration, NASA and the US Office of Commercial Space Transportation and the UK Space Agency, the Ministry of Transport, and the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). This is to allow the British side to tap into the expertise the FAA has in licencing commercial and suborbital space operations, and to gain help with US ITAR information transfer restrictions. It was specifically mentioned by Catherine Mealing-Jones, Director of Growth at the UK Space Agency, that the UK Ministry of Defence is working on solving the ITAR issues concerned with operating US-sourced hardware at UK spaceports.

Robert Goodwill had earlier explained that like the US, the UK would be regarding suborbital manned space planes as “experimental aircraft” rather than passenger carrying transports.

With respect to ITAR, Professor George C. Nield, Federal Aviation Administration, confirmed that ITAR would not prevent passengers – more correctly termed participants – from having “Informed Consent” before they flew on such experimental space planes. “(Airline) Passengers don’t have to know how to build a Boeing 747,” he noted.

Andrew Nelson, President of prospective suborbital space plane operator XCOR Aerospace agreed, explaining that for a “participant” to have “informed consent” would not involve detailed technical and engineering briefings, but rather an appreciation of the real risk and the reliability history of human rocket plane and spaceflight missions. As to whether Chinese nationals would be allowed to fly on such suborbital space missions, Nelson noted that he had received confirmation from the US State Department decreeing that civilian Chinese passengers would be allowed to fly.

How much would it cost and who will use it?

While Dr David Parker, Head of the UK Space Agency, declined to comment on whether the UK would spend as much on the spaceport and terminal as Virgin Galactic had done with its own New Mexico facility, it is thought that such a spaceport would be converted from an aerodrome at a much cheaper price. As they attempt to tap into a commercial launch market which is projected to be worth £40 billion by 2030, the question remains about who would use such a spaceport? For the time being the UK Space Agency appears to believe that “if you build it, they will come”.

George Whitesides, Chief Executive Officer of Virgin Galactic, refused to comment on whether his suborbital spaceflight firm, which also hopes to one day air-launch orbital satellites, would ever use a UK space port. However, he did note that converting an already existing runway and facilities, was probably the best way to go for the United Kingdom.

With respect to the potential of the United Kingdom building its own launch vehicle, Jean-Jacques Dordain, Director General of ESA noted that he would be in favour: “It is always good news to decrease the cost of access to space.”

On space plane operations, Dordain note that ESA had been providing technical advice to some prospective space plane operators including the Swiss Space Systems. Dordain had also noted that in some space economics and technology areas, Britain was the leader. Dordain noted how ESA was now employing public-private partnerships, most noticeably on Hylas, with the communications firm Avanti, and on Alphasat, with the mobile communications firm, Inmarsat.

Other space news at Farnborough – with glamour, tattoos and regret on show as well

At the press conference it was announced that the US firm Lockheed Martin would be setting up a “space technology office” at the UK Space Gateway centre in Harwell, Oxfordshire. It was also confirmed by Dr David Parker that the British and ESA astronaut, Tim Peake, will be launched to the International Space Station in late 2015.

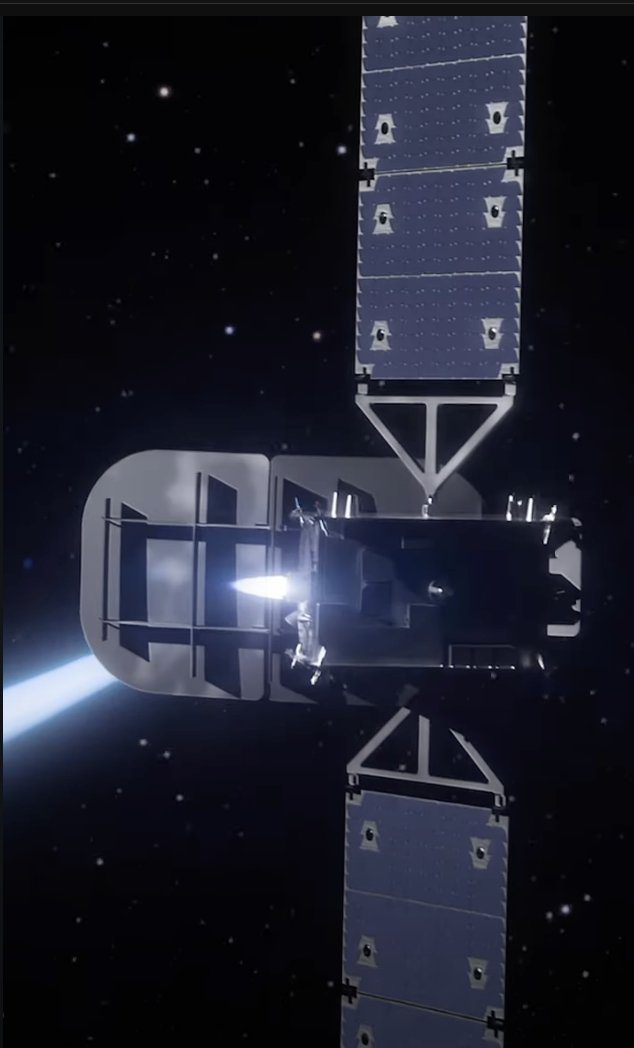

The Russo-German firm Dauria Aerospace announced a construction order for two small communications satellites for the Indian communications firm Aniara. The two satellites dubbed NextStar-1 and NextStar-2 will have all electric propulsion and will be launched as a pair by India’s GLSV rocket.

Other orders announced included LuxSpace who signed a contract with ESA at Farnborough Air Show to built two micro satellites. The contract is established as a private public partnership, where the final customer – exactEarth of Canada – will make significant investments aside ESA and the participating European companies. The total value of the two satellites is in the order of €30 million. The two satellites will be launched in 2018 and 2019 respectively. They will have a weight of approximately 100 kg and will provide very high quality AIS data for vessel detection.

While this ISS-related Soyuz flight is unlikely to be affected, relations between the UK and Russia have further deteriorated since the annexation of the Crimean region of Ukraine by Russia. The latest move (before the shooting down of a Malaysian Airlines Boeing 777 allegedly by pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine) was Britain refusing entry to most of Russia’s main delegation attending the Farnborough air show, despite the fact that Russia had just launched two of its satellites, TechDemoSat and UKube. Russian exhibition stands at Farnborough were manned however, including the space ones, presumably by personnel who got their visas ahead of the ban.

It was not just Russian attendees who were not at the air show. The show did seem to be much quieter than usual.

While he was sadly absent, the former Universities and Science Minister, David Willetts, who resigned as part of the cabinet reshuffle, was given valedictory applause for all that he had done for the space industry in the United Kingdom. There was genuine regret in the space conference audience that he had gone.

Although space remains a side-show at Farnborough – albeit a growing one – and one that commanded a visit from Vince Cable MP, the UK Secretary of State for Business, Innovation & Skills, in truth it was military and civil aviation that was really the main business done at the show.

There was disappointment in the crowd that there would be no flight demonstration of the new Lockheed Martin F-35B “Jump Jet” fighter-bomber after an engine fault had grounded the fleet, there were at least other aircraft equally relevant to past and future UK Defence Policy (or lack thereof).

As civil aircraft manufacturers such as Boeing and Airbus fought for orders, one display aircraft that fooled many into believing it was a Boeing 737-800/900 (on which it is based) was the US Navy’s Boeing P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft. Mind you its visible open torpedo/depth charge/sonar buoy bay was a major clue as to its real use. It was flying as an encouragement to buy, not least to the executives of UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), who, having also scrapped the very expensively modernised and re-engined Nimrod MRA4 aircraft (not wisely mothballed but actually cut to pieces), now realise that Britain really needs a maritime patrol aircraft after all. Bizarrely, the Boeing P-8 Poseidon was always the best and most cost effective solution for the UK’s needs rather than the nationalistic expensive rebuilding of the Nimrod MR2.

It was, of course, the same Strategic Defence and Security Review in 2010 that scrapped not only the Nimrod but also the Harrier fighter/bomber V/STOL jet. This meant that until the F-35B arrived, Britain’s aircraft carriers (including the newly built HMS Queen Elizabeth) would have no jets to fly off them until 2016 at the earliest.

If the MoD’s mainly middle-aged male politicians, civil servants, and military officers had felt too dispirited by their lack of foresight and poor decision making, albeit made under pressure from the Treasury, they could always cheer themselves up by gawping at more glamorous types on display – most noticeably those of Czech manufacture with their impressive undercarriages on the stand flogging L-39NG jet trainers.

A little less aerospace related were the scantily-clad tattooed women at the shuttle-bus bus stop at the Queen’s Parade car park presenting leaving male attendees with promotional leaflets to the “Tantric Blue Gentlemen’s Club”. While this was an ingenious bit of sexist guerrilla marketing which will no doubt will be picked up by others – the ladies will no doubt be sporting tattoos of Boeing or Airbus logos next time – your middle-aged male correspondent found that, in reality, the actually preferred the L-39NG undercarriages instead. They looked to be in a different class entirely. 🙂

.