The 69th International Astronautical Congress (IAC 2018) was held in the city of Bremen near the coast of Northern Germany. The Congress is both a technical symposium, where engineers, scientists and even lawyers present their papers, and a place where the great space powers meet in an attempt to forge better cooperation. This year’s congress was held at Bremen’s main exhibition centre located just behind its main railway station (Hauptbahnhoff).

Bremen’s beautiful town hall (Bremer Rathaus) takes pride of place in the main square along with a statue of Roland, military defender of Charlemagne. Courtesy: Wikipedia (German edition)

Bremen was previously famous for ship building, and its wartime U-boat submarine production, but has since transitioned to become the centre of Germany’s space effort. After the President of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF), Jean-Yves Le Gall, had opened proceedings, Thomas Jarzonibek, Minister for space in Germany’s federal government, noted that Bremen had been “space-ified” as it worked with the EU and the European Space Agency (ESA) on space programmes. This “Space City” now contains the German Aerospace Centre (DLR) and Airbus Defence and Space establishments.

The actual city itself has old-world charm – narrow cobbled streets in the Schnoor district, a beautiful medieval old town hall and square, and even a windmill. It does not seem to have been as affected by bomb damage and rebuilding as some other German cities, despite being an RAF target throughout World War II. Being a city close to the coast, the weather is mixed: sunny one moment, cold North Sea rain and wind the next.

The inhabitants are, for the most part, very friendly, and while they appreciate your attempt at their language, most do speak at least some English. Most of the food is of the richer, heavier kind – stews, dumplings and bratwurst – albeit with fresh fish and pickles to lighten the load.

The IAC’s opening ceremony was well run with some moments of excellence. There were a few mistakes, however. Rather than having a security bag search, the organisers elected to have bags stored instead – a system that was soon abandoned as the queues grew and many fretted that they would miss the ceremony.

Delegates head out of the IAC 2018 opening ceremony to the exhibition. Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

The Bremen Philamonia plays on as a rope dancer twirls her thing at the IAC 2018 Opening Ceremony. Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

Once inside delegates were treated to music from the Bremen Philharmonia orchestra, while acrobatic rope dancers did their bit. The event was compered by comedienne Gayle Tufts to leaven the tedium of the speeches. Meanwhile the orchestra’s conductor had the amused audience standing up and doing exercises to the music at the end of the gig.

While the overall theme of the conference was “involving everyone” in space exploration, the need for cooperation was emphasised even more. The ceremony even had a televisual message from ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst, who is on board the International Space Station (ISS). He made reference to the old African saying, “If you want to go fast – go alone,” before adding, “If you want to go far go together with others”.

The IAC event remains the pre-eminent space conference for space agencies and companies working with them. Jean-Yves Le Gall noted in his speech that the Congress had a very large 6,300 attendance and that he wanted even more at future events. While the next IAC venues have already been named as Washington DC in 2019 and Dubai in 2020, the venue for 2021 had yet to be chosen. In the end, the French capital Paris beat Venice for the selection by the IAF. This will be very convenient for the IAF President as Le Gall is also President of France’s space agency, CNES, which is also located in that fair city.

There were some other nice touches at this year’s IAC. To save the legs of some, the organisers had laid on a few electrically assisted, peddled rickshaws between the station and the venue, and it was fun giving the royal wave to your pedestrian friends as you passed them by. Likewise, full delegates were even given a free pass for Bremen’s excellent tram system – even if it ran out on Friday when needed to get to the airport. By the way, not everything in Germany runs as smoothly as Bremen’s tram system. As the result of a botched privatisation and a consequent lack of investment, Germany’s train passengers suffer “British-style” delays every day. How its passengers must wish they were in Switzerland.

The venue itself was not hard to navigate – even if a few of the major OVB halls were a long walk away from the main conference and exhibition area. The toilets and food outlets were good. The first day ended with a reception held in one of the empty halls. While a little too dark and crowded for this writer, it had a variety of traditional German food on offer as well plenty of drink, sideshow entertainments, and a dance floor.

Heads of Agency’s session had one notable absentee: Dmitry Rogozin

While the major cooperative work is done behind closed doors, the IAC has a head of agency “plenary” to air their thinking in public. This was the first IAC for new NASA head Jim Bridenstine. And the crowd immediately warmed to him when he publicly announced that, unlike previous reports, he did believe in climate change, and that the human production of carbon dioxide was a cause. (By the way, in a partial change of tune, Bridenstine’s boss, President Trump has subsequently said that he also accepts the former although he still resists the latter).

ESA’s Jan Woerner leans over towards his JAXA counterpart Hiroshi Yamakara during the Head of Agencies Plenary at IAC 2018. Courtesy: Seradata/Bremen

This year, the elephant in the room – or rather not in the room – was the head of the Russian space agency/conglomerate, Dmitry Rogozin. He had been banned from travelling to Germany due to his association with President Vladmir Putin, after Russia’s annexation of part of Ukraine. This was a hurdle rather than a barrier to attempts at international cooperation as NASA’s administrator, Jim Bridenstine, was due to meet him a week or so later when he went to Kazakhstan to see the (subsequently failed) launch of Soyuz MS-10. In the meantime, Dmitry Loskutov stood in for Rogozin and said that Russia was looking to maintain “sustainable” launch rates.

IAC 2018 Heads of Agencies’ Press Conference. From left to right: Hiroshi Yamakawa (JAXA) Jan Woerner (ESA), Maggie Aderin-Pocock (BBC), Jim Bridenstine (NASA) and K. Sivan (ISRO). Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

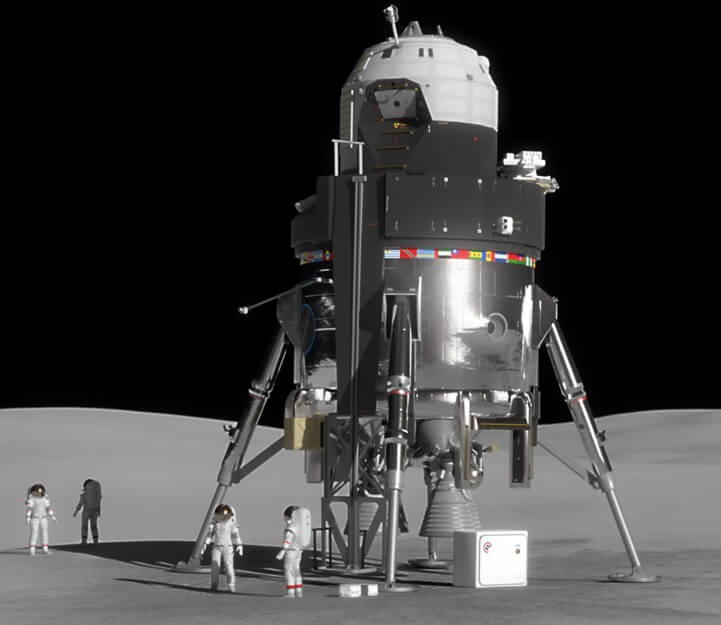

While Bridenstine said he was looking forward to the development of reusable lunar landers, at the later press conference, chaired by the BBC’s Maggie Aderin-Pocock, he responded to a question on whether he had been given a deadline by President Trump to return to the surface of the Moon. NASA’s new boss responded: “I do not have a specific time limit…The instruction I have been given is to do it sustainably.” He added that NASA’s planned lunar return was not just an Apollo-style there-and-back enterprise. In other words, despite the growing clamour for earlier rather than later human landings, this chimes with the Lunar Gateway plan as a base for lunar exploration. Nevertheless, while NASA is happy to explore the Moon, it does not want to get bogged down in building a lunar base.

Lockheed Martin Concept for reusable lunar lander operating between Lunar Gateway and the Moon’s surface. Courtesy: Lockheed Martin

A time limit Bridenstine does face is the planned ending of NASA’s funding of the ISS, and at least some of the off-camera discussions with his fellow space agency heads would have been devoted to coordinating that. With respect to international cooperation on its follow-on, the Lunar Gateway, Bridenstine said that it was too small a space station to include every space agency that wanted to take part, but that lunar exploration would provide opportunities for all. Lunar Gateway is projected to have a 15-year lifespan and would be moveable in orbit via its solar-electric propulsion module, so that it could be placed at L1 or L2, or into a lunar polar orbit if required.

Jan Woerner, Director General of ESA, agreed with him. He renewed the emphasis on going back to the Moon, ahead of Mars, when he announced his Moon Village concept a few years ago. He reiterated that this did not mean a lunar base with “houses, a town hall and church”, but rather a series of surface activities conducted by both institutional and commercial entities. “We don’t go back to the Moon, we go forward to the Moon,” he said.

Woerner reminded the audience that space agencies had transformed themselves from managing agencies to commissioning agencies. “In the past the agencies were defining everything,” he said, whereas the future would see more risk-sharing partnerships with a possible “broker function”.

The head of India’s space programme, Dr K. Sivan, reminded the audience of the threat to both human and unmanned space activities of space debris being left in orbit.

With respect to ISRO’s plans, including eventual human spaceflight, but he said that a lunar flight would be a little too far for India at present.

China has its own plans for the Moon, including the Chang’e 4 unmanned rover mission to the lunar far side later this year. However, Zhang Kejian, of the China National Space Administration, reminded the audience that in addition to its attention-grabbing missions, China’s plans also included the construction of a new recoverable spacecraft able to return 600 kg back to Earth, and the development of Ka-band communications satellites

Kejian had asked for more cooperation with NASA and said that the initial response had been positive. Cooperation with ESA is likely as some of its astronauts have already begun to learn Chinese with a view to visiting China’s planned new space station. A presentation made later in the conference noted that this would have a total mass of 189 metric tons and would consist of an initial core module and two experimental modules.

Sylvain Laporte, President of the Canadian Space Agency, noted that his country was looking forward to the launch of its radarsat constellation, dubbed Radarsat 2.

Hiroshi Yamakawa, head of Japan’s JAXA agency, basked in the adulation that followed the recent Hayabusa 2 spacecraft arrival and subsequent Minerva II landings on an asteroid (the DLR would later celebrate the landing of its own MASCOT small hopper lander). Yamakawa looked forward to his agency’s lunar mission and a foray to the moons of Mars via its planned MMX mission to Phobos and Deimos (to launch in 2024), which will carry instruments for NASA and the French agency CNES.

When asked if there would ever by an “International Space Agency”, Yamakawa responded: “Is one needed now we are working together?” With respect to the threat of space debris, he made the point that JAXA was working on active debris removal technologies.

SpaceX was there – but without Elon

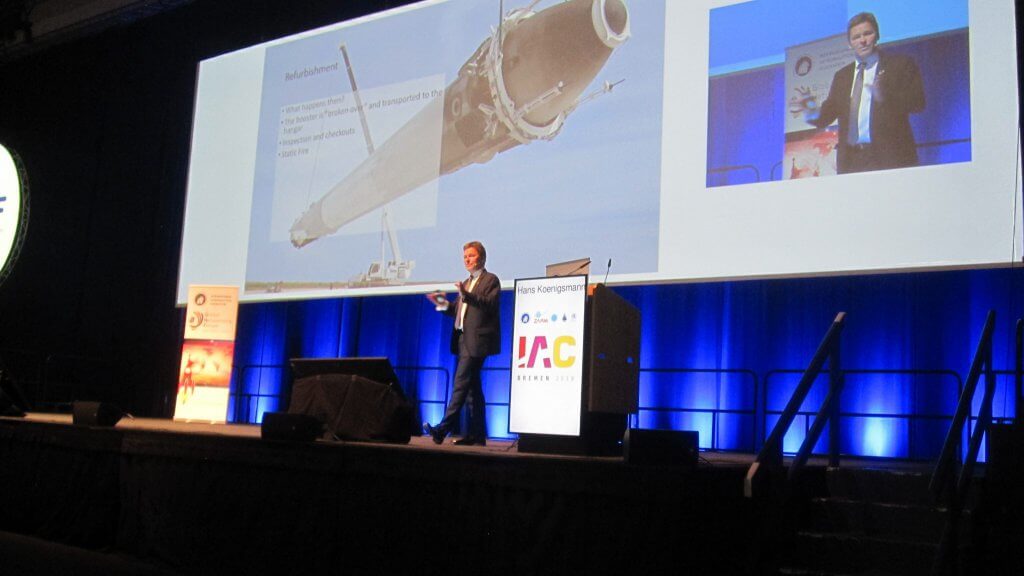

Hans Koenigsmann explains the benefits of being able to examine how to get better during refurbishment of reused first stages. SpaceX. Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

Elon Musk, head of SpaceX, was also a notable absentee given his appearances at the previous two IACs. His technical No. 3 (after Gwynn Shotwell) Dr Hans Koenigsmann stepped up to the plate during a special Global Networking Forum (GNF) lecture to explain the advantages of interactive change in the light of the Falcon 9 reusable launches. “We just learned from time to time,” said Koenigsmann, who indicated that test flights were used to verify their original analysis. “We trust our tests more than our analyses,” he added.

At a subsequent GNF forum Peter McGrath, of Boeing, reminded the audience that apart from a performance penalty, reusability has its economic limits. NASA eventually gave up trying to reuse the parachute and splashdown recovered Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) when it realised that it cost about US40 million extra per year to do so.

Koenigsmann described the demarcation in the regulations relating to launches from the two pads SpaceX uses on the US East Coast. Pad 40, at Cape Canaveral, is under US Air Force rules, while the Kennedy Space Center’s Pad 39A is under NASA rules. He went through the history of the firm, describing its growth from 14 employees in 2002 to over 6,500 today. The latter figure and a quick analysis of their salary needs made some in the audience wonder just how SpaceX was able to launch its rockets so cheaply?

He defended the planned BFR/BFS launch vehicle/spacecraft combination with a “straight bat” when asked how the BFS spacecraft would survive an Earth atmospheric re-entry at Mach 30+. “I don’t think that the Mach number is relevant,” he said. He agreed, however, that the heating rate/flux was very much dependent on velocity. According to the entry angle chosen and the vehicle’s density (via the ballistic coefficient), he contended that SpaceX’s thermal protection system could still handle the heating during a lunar or Mars return. There was no word from him about whether active cooling would be needed, or whether the craft’s lift vector would be used to hold it in the atmosphere for long enough to get below super-orbital speed.

On a lighter note, Hans Koenigsmann had earlier quipped that having a German accent was an advantage for a rocket scientist applying for jobs in America. However, his final words to those thinking about a space career was that when it came to rocket engineering, “talent was more important than experience”.

The other GNF and Technical Sessions

The lecture sessions covered everything from rocket engine design to space history, so it was often impossible to see everything you wanted to because several strands of lectures coincided. This was aggravated by the growth of the Global Networking Forum lectures and discussion panels. While these were often more interesting than some of the main plenary sessions, the GNF has now become a “conference within a conference”, which risks usurping the main event.

During a GNF panel session covering European launchers, Jan Woerner, of ESA, defended the expendable Ariane 6. He stressed that it was essential for Europe to have its own launcher system, especially after its experience with the Symphonie communications satellites. After the failure of the Europa rocket programme in the early 1970s, Europe found itself without a launcher. The USA agreed to launch the satellite pair – but only on condition that they would NEVER have a commercial use as the Americans attempted to defend their satellite construction and operator business. The lesson for Europe was that while it should cooperate with other nations, it should only do so from a position of strength. Woerner was disparaging about SpaceX’s sportscar stunt on the Falcon Heavy launch, but he admired the firm’s agility in making changes so fast – more or less every flight – although he pointed out the serious risk element. However, he also admitted: “No Risk. No Fun”.

Model of French experimental reusable rocket Callisto – with a remarkable similarity to SpaceX’s landing gear. Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

If you cannot beat SpaceX, copy it. One stand in the exhibition had a model of the French experimental reusable rocket Callisto – its landing gear make it look remarkably like a Falcon 9.

Luce Fabriguettes, of Arianespace, told the audience there had been a significant slowdown in GEO communications satellite orders, and this would lead to difficult years for the launch industry before the LEO constellations arrived. Others fretted about ordering an Ariane 6 launch when it was not yet flying. Marco Fuchs, of Greman satellite manufacturer OHB System, said: “I cannot rely on Ariane 6 as it is not confirmed yet.”

Of the technical sessions, the ones this writer managed to attend were on the Lunar Gateway and the SLS, and some on space architecture related to lunar exploration.

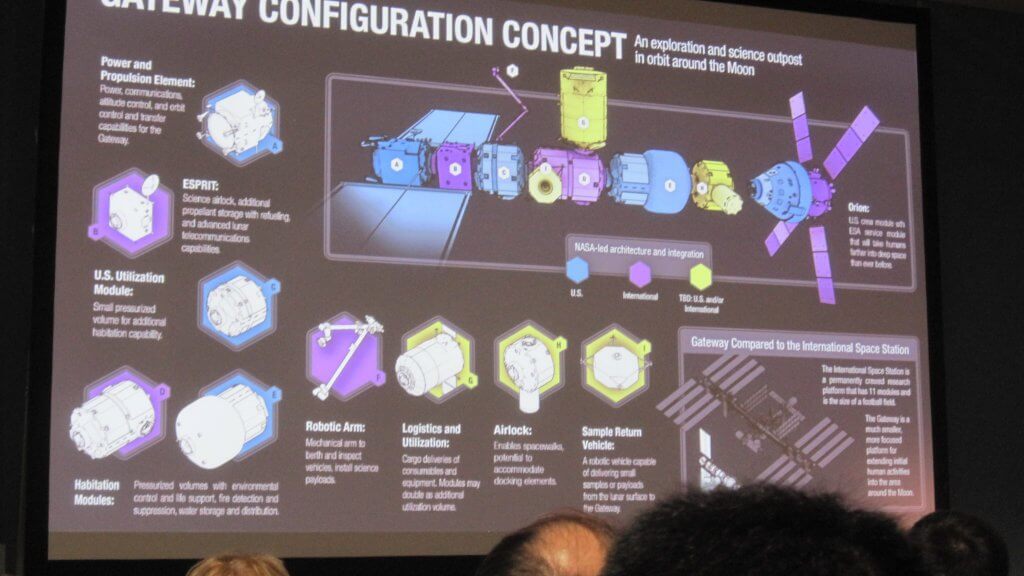

While Europe’s “The Space Race” – a very vague not-for-profit organisation promoting lunar exploration was announced at the Congress, with Blue Origin in support, on sounder ground was.Jason Crusan, of NASA, who presented an excellent paper (IAC-18.A5.1.1) showing the main elements of the Lunar Gateway. He explained that several configurations were being considered and noted the role that commercial launch vehicles would play in launching some of the elements. With the use of the solar/electrical thrust module and Earth flyby’s, the station would be able to reach lunar polar orbits and well as L1 and L2.

Attendees in a “sold out” lecture on the Lunar Gateway look at the main elements of the outpost in Jason Crusan’s lecture (IAC-2018.A5.1.1.). Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

Crusan reiterated the point that Bridenstine had made earlier: at only 125 cubic metres, it was only about 10 per cent of the size of the ISS. Crusan envisaged that the Gateway would be used for human stays of between 30 and 90 days. Increasing use of RFID chips would help monitor logistics on board the vessel.

While Bridenstine had warned that the Lunar Gateway might be too small for large-scale international participation, others were worried about any delays it might cause. “It will take longer to get a partnership agreement than it will to launch hardware,” mused NASA’s Kirk Shireman as he presented the following paper (IAC-19.A5.1.2).

While the lunar village will NOT be needing a town hall (“rathaus” in German,) as Woerner reiterated, some papers at the Congress noted that lunar structures might need a different architectural approach. These included Sandra Haeuplik-Meusburger’s presentation of her Technical University of Vienna students’ architectural designs for different elements on the Moon (IAC-18.A5.1.8). Some of the designs looked better than others – even if they were partially underground for radiation reasons.

TU Vienna student architectural design for a astronaut lunar training centre with the habitat partially underground. Courtesy: TU Vienna

Christiane Heinicke, of the University of Bremen’s Centre for applied Space Technology and Microgravity (ZARM), presented a design for a Moon and Mars Base Analog (MaMBA) (IAC-18.A5.1.14). She explained that architecture on the Moon was likely to be driven more by utility than aesthetics, but architects would still be needed for the ergonomics, safety, and light and sound requirements. Somewhat disappointing architecturally – even allowing for its protection needs – was the design for the Centauri Lunar Hotel Alpha (IAC-18.A5.1.9). This was no high-end Hilton – more like a single-story motel.

The Exhibition

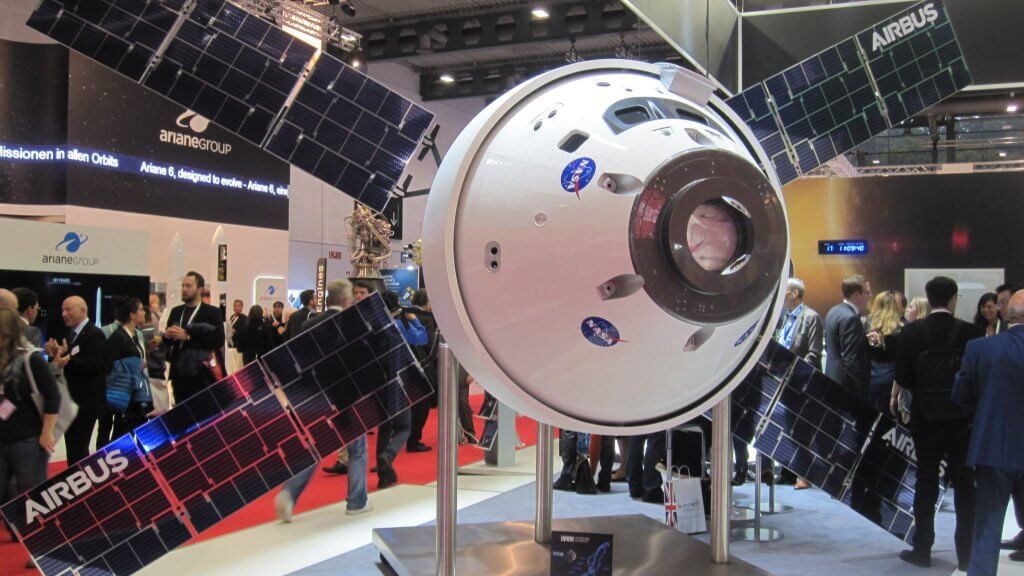

The IAC 2018 Bremen exhibition was impressive and reportedly much larger than that at IAC 2017 Adelaide. Most of the major firms involved in space exploration were present. The Airbus stand probably took the prize with an excellent model of Orion and its service module. If there was one criticism it would be that the public day was held too early in the week. Wednesday was effectively a washout for business proper when 10,000 members of the public crowded into the hall on their ‘German unification’ day off.

Megan Clark, head of the newly formed Australian Space Agency, made the point that some Australian visitors to the Congress were thrilled to see that Australia finally had a presence. “We’ve got a booth! We’ve got a booth!” they excitedly shouted. And a major one at that, to the point that some other space agencies’ stands, e.g. that of Romania, were effectively hidden from view. Australia, by the way, was NASA’s only official international partner during the Apollo lunar missions.

“Sexiest” exhibit on show was the “Spaceliner” rocket plane concept design from DLR. While this will probably always be just a paper project, at least we can all dream.

The UK pavilion was small but well positioned, right next to NASA’s surprisingly modest stand. Like NASA’s the UK pavilion lacked a bit of vertical presence – it really needed Union flag above it. As part of it, Seradata’s stand was at least well positioned being opposite Boeing’s exhibit with its CST-100 Starliner commercial crew capsule simulator.

Meeting and greeting in front of the British Interplanetary Society’s Stand/Booth as part of the UK Pavilion at IAC 2018. Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

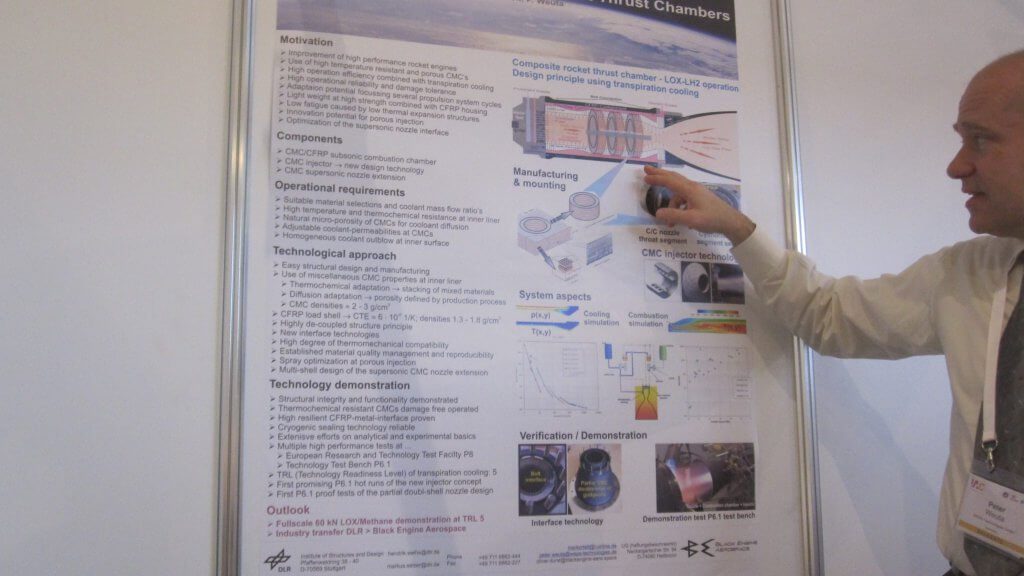

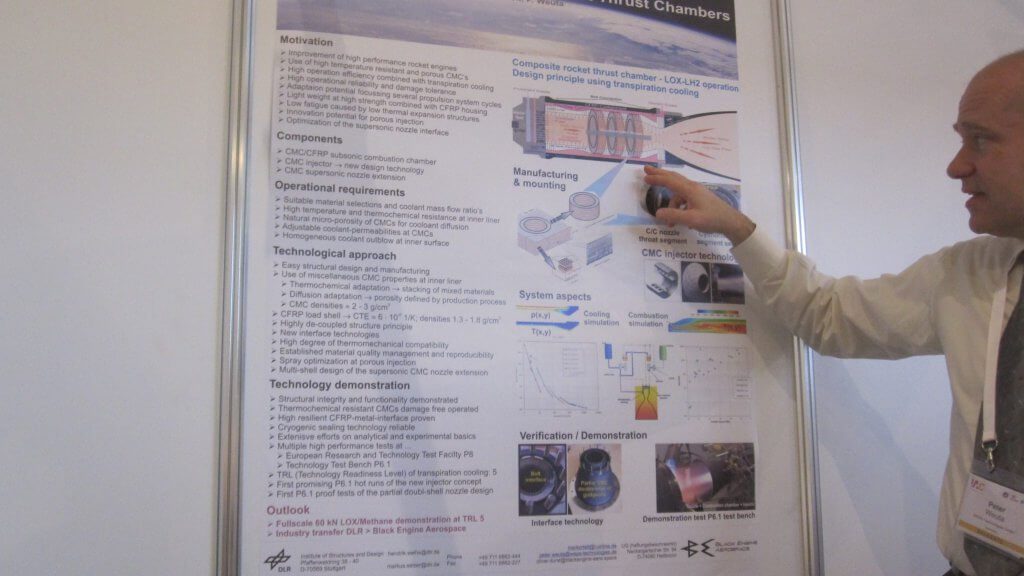

One booth slightly off the beaten track – well actually in the corridor near the main exhibits – was that of Black Engine Aerospace – a company spun off from DLR. It was marketing a type of ceramic rocket engine using a porous wall to transpirationally cool the thrust chamber, using hydrogen tapped off from the fuel.

Being shown the basics of transpirational cooling on the Black Engine Aerospace stand at IAC 2018. Courtesy: Seradata/David Todd

And jolly interesting it seemed too with claims of 4,000K temperatures and 60 Bar pressures being achieved, and for a 75% lower cost than using regenerative cooling. One wonders, however, whether the core CFRP (Carbon Fibre Reinforced Plastic) matrix could maintain its structural strength at these temperatures – cooled or not – for long.

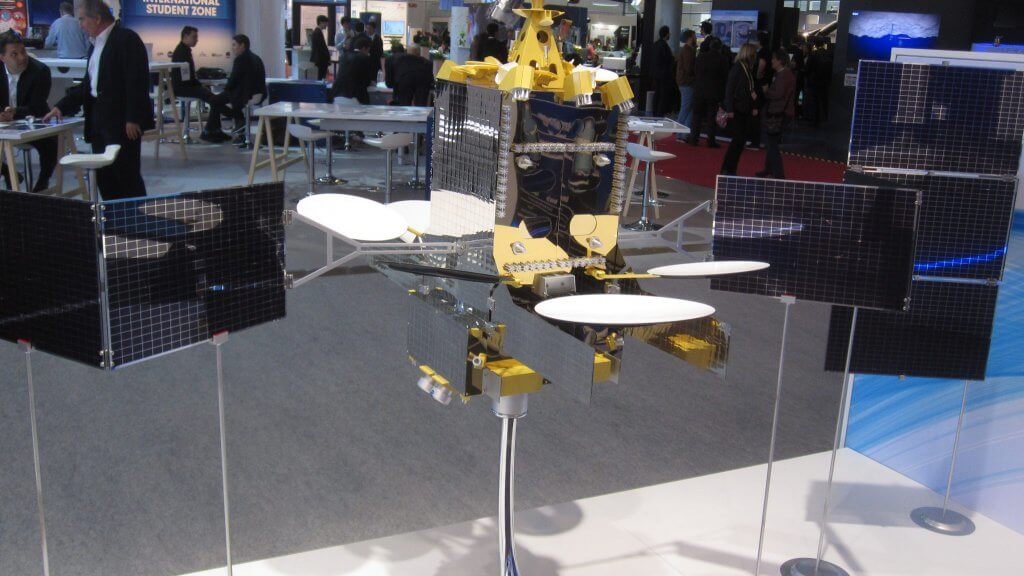

China had a strong showing with state firms, including CAST, CASIC and CALT, and “private” firms such as LandSpace displaying their rockets and satellite designs.

Apart from the paid-for main Gala in the Rathaus (old town hall), the IAC also laid on various paid-for and free cultural and technical tours, whether to a local bierkeller or to Airbus DS or to DLR. This writer went to DLR – officially known as Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V (German Aerospace Centre). It was interesting to see its research on lunar landing gear, and the EU:CROPIS spacecraft in the clean room just before shipment to the Vandenberg launch site ahead of its Falcon 9 launch. That spacecraft will use its spin to mimic both lunar and Martian gravity as tomato plants are grown on board.

The closing ceremony reportedly involved a somewhat confused prize giving. Holding up the British end was Shaun Andrews, an aerospace engineering student at Bristol University, who took the Gold Medal for best undergraduate paper (IAC-18.E2.2.10), on modelling plasma drag on ion engines in very low orbit. Andrews hopes to work on revolutionary forms of spaceflight engines in his future career.

Overall, most delegates seemed to enjoythe IAC 2018 Bremen Congress and probably learned something from it. Despite international tensions triggered by the “usual suspect” politicians over the past couple of years, at least the scientists, engineers and even the heads of space agencies still appear to want to cooperate. That is, if their political masters will let them.