The Presidential directive to put humans on the Moon by the end of 2024 is concentrating the mind of NASA’s leadership. To some extent NASA’s hands have been bound by past equipment choices with the ever-present problem of having very limited funds to enact such a plan. Thus, NASA finds that it has to make the best of what it has got. This does not mean that a NASA human lunar landing mission will not be possible, but it may have higher risks than using a bespoke design, and it may not make the 2024 deadline.

Gateway is needed because Orion does not have enough juice

NASA’s Artemis programme is currently wedded to the Gateway (aka Lunar Gateway) space station. The reasons? During the IAC Heads of Agencies press conference, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine explained that the delta V capability of the Block 1 SLS combined with the Orion service means that Orion is limited in high lunar orbit and thus needs a waypoint for crew to transfer to a lunar lander. “With the SLS rocket and the European Service module we don’t have enough delta V (velocity increment) to get into low lunar orbit and out of low lunar orbit,” Bridenstine said.

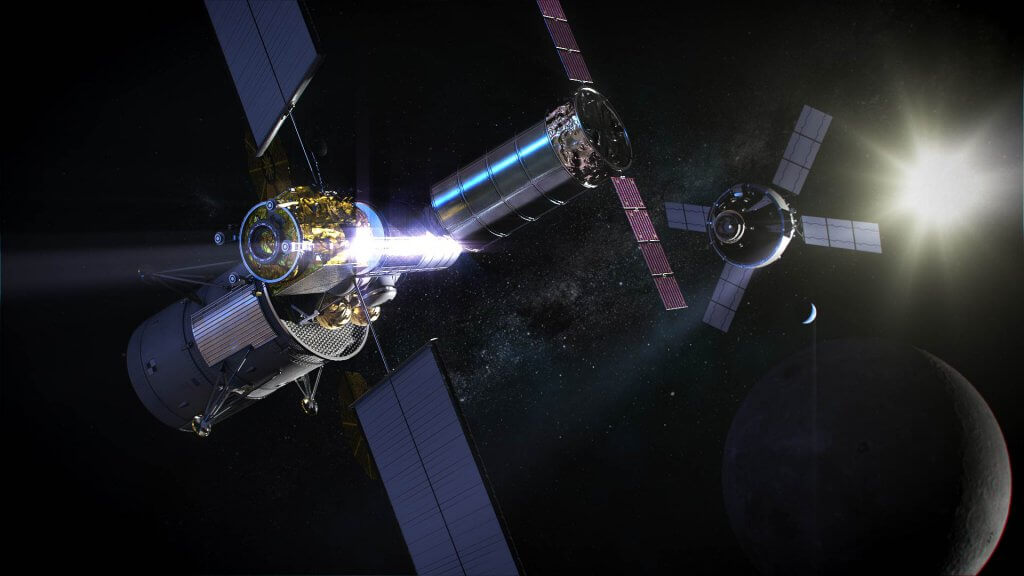

Lunar Gateway Habitation Module attached to Power and Propulsion Element with visiting Cygnus cargo and Orion spacecraft. Courtesy: NASA

Nujoud Merancy, Chief, Exploration Mission Planning Office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, echoed her boss when she explained that the Orion craft and its European-built service module “do not have enough juice” to get to a low lunar orbit AND return to Earth. In other words, ahead of any landing, whether they use the Lunar Gateway or not, any landing craft will need its own transfer stage or extra transfer capability to move from high to low lunar orbit.

With the benefit of hindsight, Orion should have had a larger service module to make it all the way to low lunar orbit, but had its size originally restricted by the payload capabilities of the initial Block 1 version of the SLS with its single RL10B-2 engine Interim Cyrogenic Propulsion System (ICPS) upper stage. Nevertheless, while necessity is the mother of invention, Bridenstine remains a supporter of the Gateway space station emphasising that it offers the quickest path to the lunar surface.

Bridenstine pointed out that the Gateway would enable full accessibility to all lunar latitudes between the poles via its solar electric thruster system. It would also provide a sustainable capability via its 15-year projected lifespan. “The Gateway brings so much more value than just speed,” he said.

The “high lunar orbit” chosen for the Gateway outpost is actually a “near-rectilinear halo orbit,” which will bring the station as close as 3,000 km to the lunar surface. This orbit has the benefit of continuous solar illumination and continuous communications with Earth, acting as a relay for lunar surface operations. There are some downsides. Critics note that it does take considerable accuracy to place the spacecraft into this orbit and that, contrary to reports, a considerable amount of station keeping fuel will be needed.

Critics of NASA’s current plan to put humans back on the Moon have suggested that a two-launch strategy without the use of a Gateway lunar space station would be better for a quicker landing on the Moon.

While NASA finds itself slightly forced into adopting the Gateway plan by previous architecture choices, there is one other upside to it. Bridenstine accepts that the Gateway might have a spin-off use as the basis of a low Earth orbit space station designed to replace the ISS. “We could have a dozen of them,” he said.

In fact, ahead of any lunar return, this is NASA’s and its commercial crew effort’s most pressing need or soon they will have nowhere to go in low Earth orbit.

New lunar landers: Will Viper rover find enough ice for propellants for Blue Origin?

While NASA is planning some unmanned missions first, the current proposal is to have two partially reusable lunar lander designs for human use sourced commercially. The initial landing of one of the two successful lunar lander entries is scheduled for 2024.

The original idea was that both lander alternatives would be modular (a crew/ascent capsule, a landing stage and a transfer stage), and that they would be fired to the moon in three parts on different, probably commercial, launches. These would be assembled into a single spacecraft which would be fueled at the Lunar Gateway before a landing took place.

At the IAC, Jeff Bezos announced the formation of a “National Team” to bid for a full lunar lander stage – ascent stage – and transfer stage craft. The team would have Lockheed Martin building a crewed ascent stage and Northrop Grumman, famous for its original Apollo lunar lander, building the transfer stage. The team would be led by Blue Origin, with a version of its Blue Moon lander as the lander stage. Draper is developing the craft’s guidance and navigation systems.

Which propellants are to be used for the landers is currently the subject of trade-off studies. Blue Origin has decided to employ the cryogenic pairing of liquid Hydrogen and LOx (liquid oxygen) at least for its Blue Moon lander, noting the advantages in the longer term of being able to “mine” water on the Moon as a source for these. Other teams are believed to be considering storable propellants as they try to avoid the downsides of heavy cryo-coolers and having to cope with high boil-off rates.

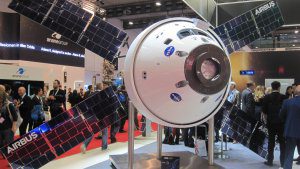

Model of Blue Moon landing stage shown at IAC 2019 Washington DC. The stage will use cryogenic propellants. Courtesy: Seradata (David Todd)

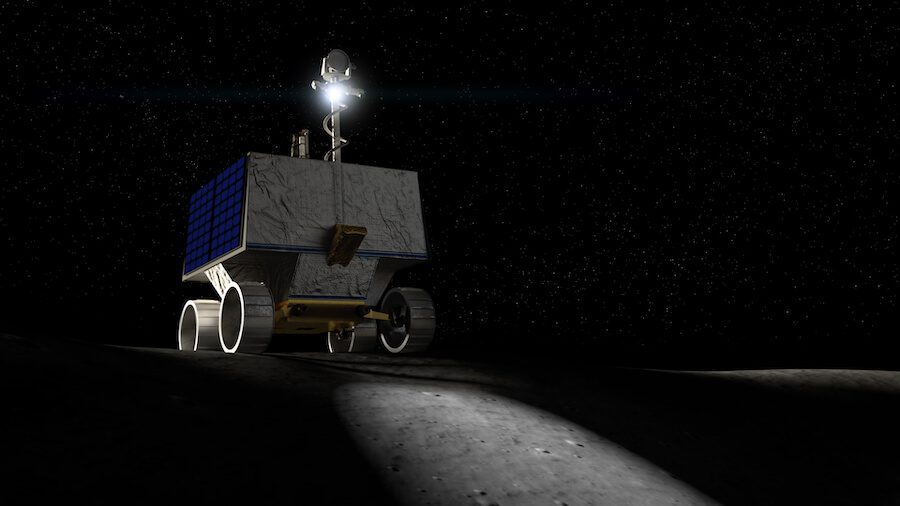

While the disadvantages of cryogenic fuel technology are obvious, the promise of mining these propellants in future is seductive. Its advocates received a boost from NASA. It has resuscitated a plan to use a rover to investigate the South polar region of the Moon, specifically in a search for water deposits. This Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) mission, worth US$250 million, will be launched in December 2022.

Boeing says SLS Block 1B launching a complete lander is a better choice

While the current NASA plan envisages several launches to get parts of the lunar lander into lunar orbit, Boeing’s Benjamin Donahue (IAC-19.A5.1.1) convincingly argued there is an alternative to the modular lunar lander plan. He suggested that quickly building the powerful Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) which is equipped with four RL10-C3 engines for use on the SLS, would raise its current 26 metric ton TLI (Trans Lunar Injection) capability to the 34-40 metric ton range. This would allow the lunar lander to be launched as a complete craft, reducing the number of launches and docking events, and hence the risk of a module/stage being lost.

In a “two-launch” strategy, Boeing and its political confederates suggest that the crew could be launched on a single EUS-equipped SLS Block 1B and the complete lunar module would be launched on another cargo SLS Block 1B. Meanwhile, the fuel (propellants) would be launched by a commercial launch vehicle.

Since the IAC, Boeing has put further detail on this idea. It has formally announced its proposal for a single two-stage lunar lander, which would have a lunar transfer capability. This would rendezvous at the Gateway in its near-rectilinear halo orbit and would take on a landing crew taken there by a SLS-launched crewed Orion. Alternatively, it could meet up with a crewed Orion in similar high lunar orbit ahead of the lunar landing with no Gateway required. It is assumed that in either case the landing/ascent craft would still need top-up refuelling ahead of any lunar landing.

During a later question and answer session on the NASA stand at the IAC exhibition, Bridenstine noted that an EUS stage had other advantages, including making the launch opportunities for lunar missions more regular and offering schedule robustness. While in favour of developing the EUS, he cautioned that it would be up to Congress and its House Appropriations Committee to decide whether it would be built.

With his stylish brown shoes on NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine makes a good job of explaining why EUS is a good idea. Courtesy: NASA

Bridenstine knows that oncoming commercial launch offerings, in the shape of SpaceX’s Starship/Superbooster,and Blue Origin’s New Glenn (and possible New Armstrong) rockets will have performance and cost advantages that are likely to eventually usurp the US$2 billion-a-launch SLS Block 1B completely. These may make any appropriations committee think twice about funding the SLS Block 1B and its EUS.

Without EUS NASA will have to make the best of what it’s got

While agreeing that the EUS equipped SLS Block 1B was attractive from a mission architecture standpoint, Michael Sarafin, NASA’s Artemis Mission manager, noted that the EUS would not be ready to fly until 2025 – later than would be needed to achieve President Trump’s 2024 human lunar landing deadline.

The current Artemis mission running order has Artemis 1 (formerly known as EM-1) flying the Orion in an uncrewed condition to a distant retrograde orbit in late 2020/Early 2021. A crewed Orion will be used for the lunar flyby Artemis 2 mission in 2022. This will act as a shake-down mission for an actual landing attempt by Artemis 3 in 2024.

Sarafin ruefully gave the traditional NASA riposte on whether EUS would be built: “No bucks…No Buck Rogers”, before adding, “so we have to manage with what we have got.”

And for the time being that means the Block 1 version of SLS with the ICPS upper stage, the Gateway human-tended space station, the somewhat limited Orion spacecraft, plus any assemble-in-space modular commercial landing craft and rockets going.

Steve Creech, NASA’s SLS payload integration and evolution manager, agreed with Sarafin’s point about EUS probably not being ready in time: “EUS would have to be accelerated to make a lunar landing,” he said. As it is, with NASA struggling to get enough funding to make the 2024 landing date even with the current plan, it is a big ask to get the EUS development accelerated.

Nevertheless, as he searches for suitable unmanned interplanetary missions to fly on it (IAC-19.A5.4-d.28.1), Creech remained proud of the SLS describing it as the “largest rocket stage ever built”.

Michael Sarafin had earlier admitted that the Apollo programme’s Saturn V – with its even greater payload to TLI than SLS – would have been useful in planning a lunar return. But he pointed out that SLS electronic systems and manufacturing, especially its tank friction stir-welding techniques, were far in advance of Saturn V’s technology.

Nevertheless, one cannot help wondering whether, if NASA still had Saturn V, or had at least spent a bit extra to build a larger payload version of the SLS in the first place, a Lunar Gateway would be needed at all.

Post Script: Space News reports that ULA has gone cold on ACES upper stage for its Vulcan rocket favouring instead a stretched version of the Atlas V Centaur stage with Aerojet Rocketdyne-supplied RL10C-X engines. This author has long suggested that such a stretched upper stage – a kind of super ICPS – would be ideal as a low cost upgrade to SLS, giving it a TLI performance approaching that of an EUS-equipped SLS Block 1B.