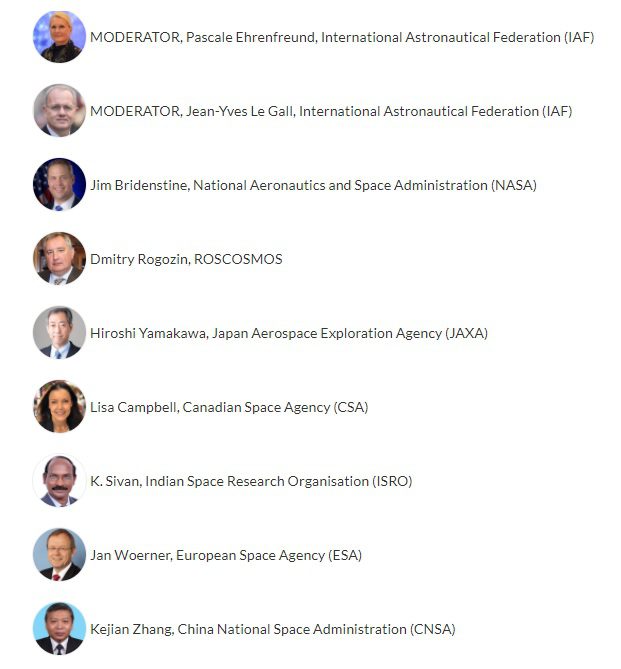

At the Heads of Space Agency online plenary at the International Astronautical Congress IAC 2020, Jim Bridenstine, NASA’s Administrator, started his presentation with the quote that “Competition is a driver, collaboration is an enabler.” By cooperating, nations would be able to help each other achieve their space aims. He cited the international popularity of the Artemis plan to put humans back onto the Moon, with many nations wanting to take part (writer’s comment: other nations are champing at the bit to get their astronauts on the Moon). When asked about whether the Covid-19 pandemic had affected NASA seriously, Bridenstine said that it had delayed some missions but that personnel had learned to work around the restrictions.

This was reiterated by Jan Woerner, Director General of the European Space agency, who said that ESA had suffered launch delays and cost increases, but that teleworking had worked well, and that the pandemic had actually accelerated ESA’s plans for a “digital transformation”. Woerner reminded the audience that this year’s IAC was his final one as head of ESA. He listed recent ESA successes and future projects including: LISA, Copernicus, Bepi-Colombo, Galileo, Ariane 6, Vega C and the Space rider mini-shuttle.

Bridenstine was keen to mention how NASA technology was being employed in the fight against Covid-19. Sterilising “foggers”, normally used for space probes, were now sterilising ambulances.

China’s Kejian Zhang, Administator of China National Space Administration (CNSA), reported that spectrometers designed for space research were being used for virus detection.

With respect to working with other nations on space exploration, Zhang noted that China was fully in favour of space cooperation, saying via an interpreter: “We can actually unite to achieve greater success.” Zhang later described how China had worked successfully with Brazil on the joint long-standing CBERS (China Brazil Earth Resources Satellite) programme.

Zhang stated that his country had made 37 launches in 2019 with 25 flown so far this year, including the successful launch of the future mainstay of China’s national launches, the Long March 5B. As China looks forward to lunar missions, its Chang’e unmanned lunar probe design team, Wu Wieren, Yu Dengyun and Sun Zezhou, were awarded the prestigious IAC’s World Space Award medal.

Dmitry Rogozin, head of Russia’s space agency/space conglomerate, is often portrayed as the “bad guy” of space – mainly due to his close connection to Russia’s international law-breaking president, Vladimir Putin. Apart from being subject to international sanctions due to this connection, Rogozin has recently come under internal fire from ex-cosmonauts for his handling of the Russian space programme. Despite this and the worsening of US-Russian relations, Rogozin maintains a friendship with NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and made a point of noting Russia’s good relationship with his US opposite number.

Rogozin said that Russia would like to keep the International Space Station working until 2035 – about ten years longer than currently envisaged. He explained that good research was being done on the ISS, including on the long-term effects of long-range space missions. Rogozin also confirmed that Roscosmos planned to launch its NAUKA multipurpose module to the ISS next year. This will be used for various biotech and optical research projects.

In respect to what follows the ISS, Rogozin was critical of US’s Lunar Gateway mini-space station project saying it was “too US centric”, meaning that the USA had too much sway over the project. While Russia does not formally take part in the Gateway programme – given recent geopolitical tensions between Russia and the USA (and other Western nations) this is looking less likely – Rogozin hopes that a common/universal docking module will be designed so that Russia’s new cosmonaut-carrying Orel spacecraft can at least dock with it – if only as a potential rescue measure.

In response to a question, Rogozin said he saw the Moon BOTH as a stepping-stone to long range exploration AND as part of long-term space infrastructure. As a sign of change in Russia’s space partners, he noted that Russia was reaching out to China. He also declared that Roscosmos would soon be testing lunar landing technology on the Moon.

Lisa Campbell, new President of the Canadian Space Agency, described how Canada wanted to grow its space sector given its economic potential. She hoped to learn from other countries’ space industries. When asked about climate change in a subsequent press conference, she read out a prepared answer on how Canada’s space effort might help research. Her rather rambling reply did note that free data access was one thing that her agency was striving for so that scientists around the world could benefit. Pointedly, in this new era of geopolitical tension, Campbell stated that Canada was a “reliable partner” for space cooperation.

The Chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation, Dr K. Sivan, was especially strong on ISRO’s attitude to space cooperation – not only for its own benefit but also for the benefit of other less advanced space nations. For example, Dr Sivan said that part of the reason why India’s human space programme was advancing so rapidly was that it was receiving help from other spacefaring nations. He noted Russian technical aid with the testing of ISRO’s crew module, the design of its life support systems and crew training. Meanwhile, on the scientific front, ISRO was cooperating with both NASA and the US National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on scientific and exploration research, and with JAXA on a joint lunar polar mission. It was even working with Israel on electric propulsion systems. Sivan explained that ISRO was not just a taker, it was also giving back by helping developing nations with their nanosat projects.

Hiroshiu Yamakawa, President of Japan’s JAXA space agency, spoke of the keenness of his nation to take part in the Global Exploration Plan and especially NASA’s Artemis project to return humans to the Moon. He explained that there would be Japanese technology on the Moon-orbiting Lunar Gateway mini-space station.

Apart from the unmanned Lunar Polar Exploration Mission (LUPEX), on which JAXA is cooperating with ISRO, Yamakawa said the agency was also working on the Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) mission. This involves developing a smart lunar lander for pinpoint landings on the lunar surface. JAXA was developing a pressurised lunar rover for human use, he said, as well as planning a small sample return mission called Martian Moons Exploration (MMX).

Yamakawa was later asked about progress on plans for hydrogen production on the Moon and whether this would aid “sustainability”. Yamakawa said that he did foresee such technology being used but that it would “take some time” to develop and implement.

Later in the post-match press conference, the subject came up of whether there should be international regulation of space debris. ESA’s Jan Woerner implied that good behaviour should normally be voluntary. “I don’t need a regulation to stop me killing people,” he said.

Conduct in Space came up again when NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine was asked about the Artemis Accords, which he had brought in as a template for international standards. He explained that these accords were not really new. “The Artemis Accords reinforce the Outer Space Treaty.” The implication is that if a nation hoped to put its astronauts onto the Moon via NASA’s Artemis programme, it would have to sign up to the accords. Bridenstine subsequently revealed that eight nations including Australia, Canada, Italy, Luxembourg, Japan, the United Arab Emirates, the UK and the USA itself had signed up to them.