Farah Ghouri looks back at the life, barely begun, of OSAM-1 after the refuelling demonstration mission is axed by NASA

The idea for OSAM-1 (On-Orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing 1), first known as RESTORE-L, was conceived in 2015, in a bid to help extend the operational life of satellites in space. Crucially, the project was aimed at refuelling older satellites already in orbit – meaning satellites not designed or built to be serviced. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland was tasked with the project and an order for RESTORE-L was placed in December 2016. The goal was to refuel and repair an aging US remote sensing satellite, LANDSAT 7, which at that time had already spent 17 years in orbit.

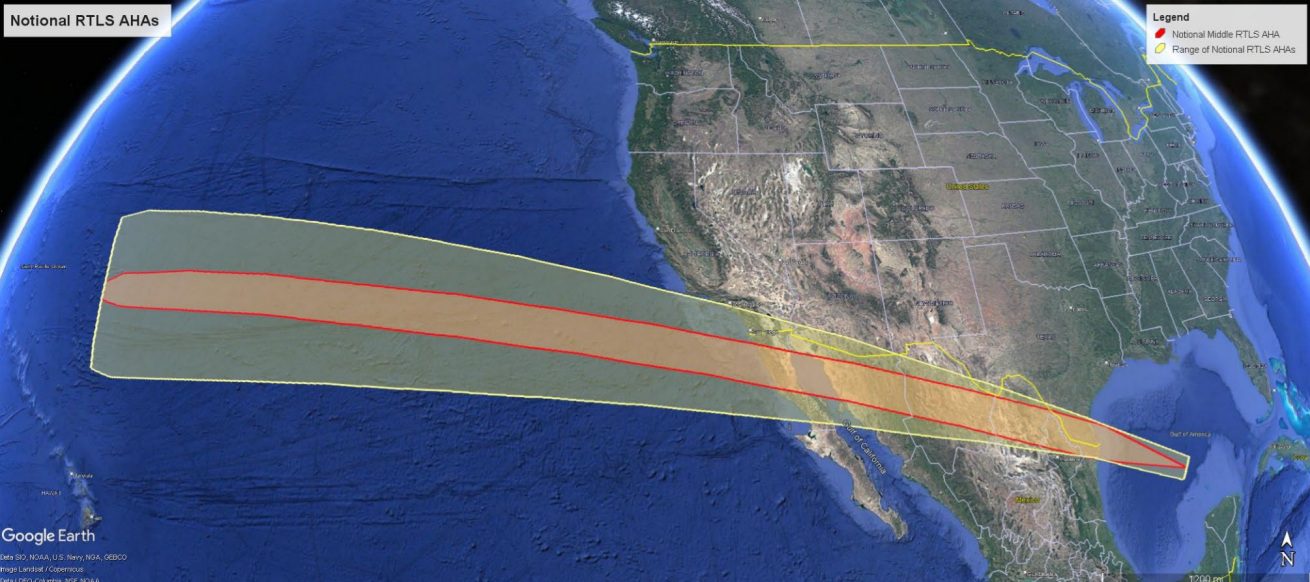

The OSAM-1 mission was cancelled by NASA, seven years after it was first ordered. Courtesy: NASA

Four years in, the project arrived at its original planned launch date in 2020. However, instead of launching, NASA turbocharged plans and announced a new, even more ambitious mandate: to pull off the world’s first autonomous robotic in-orbit satellite servicing, assembly, and manufacturing mission using a robotic arm. The project was re-named OSAM-1 and Maxar Space Systems was awarded a US$142 million contract to develop the robotic arm known as the Space Infrastructure Dexterous Robot (SPIDER) payload. The doubtful value of SPIDER would later come to light in a damning independent review of the project, published in February, that found multiple people on the programme “expressed ambivalence about SPIDER’s value to NASA”.

All the while, OSAM-1 continued to be developed but was no closer to the launchpad. Delays continued to afflict the project until finally, seven years after it was first ordered, it was cancelled by NASA – by which point OSAM’s final expected launch date had been pushed back to March 2028, and costs had ballooned. During the time it took NASA to decide to cut its losses, around $1.4 billion had already been spent on the refuelling project by November 2023, according to the independent review, commissioned by the Space Technology Mission Directorate. Worse still, the review found that the projected total cost of the mission at completion had risen to $2.4 billion.

When NASA announced in March that it was shelving the project, it pointed a large finger directly at its prime contractor Maxar. The agency said that “continued technical, cost, and schedule challenges, and a broader community evolution away from refuelling unprepared spacecraft, led to a lack of a committed partner”. In a blistering audit, published in October, NASA’s Inspector General concluded that “much of the project’s cost growth and schedule delays can be traced to Maxar’s poor performance on the spacecraft bus and SPIDER contracts with each deliverable approximately 2 years behind schedule”. Maxar itself acknowledged that it had “significantly underestimated the scope and complexity of the work”.

However, other contributing factors were highlighted, including the nature of NASA’s Fixed Firm Price (FFP) contracts which did not allow “adequate flexibility to incentivize Maxar to improve its performance”. Another. rather glaring, problem identified was that Maxar was no longer profiting from its work on OSAM-1, due to the contract structure as well as the project schedule and cost overruns.

Physicist Dr. Rob Hoyt, who was involved in MakerSat, an experiment planned to fly on OSAM-1, made scathing remarks about NASA’s handling of the project in a LinkedIn post. NASA “imposed dramatic changes in requirements” that drove up the expenses of a supposedly “low cost” project, according to Hoyt, who attested that the agency then “expected my small business to pay for all of the scope increase”.

Comment by Farah Ghouri: It seems reasonable to probe the concept of OSAM-1: to find a way of resuscitating large, aging satellites – never designed to be refuelled – so that they would last a few more years. That idea was shaped close to a decade ago and, to put it kindly, has not aged well. NASA should perhaps have focused its attention on the satellites of the future, which are more likely to be designed with refuelling in mind.

Achievements in refuelling technologies, driven by commercial entities, throw the failure of OSAM-1 into sharp focus. Orbit Fab – a private company focused on replenishing satellites that are designed to be refuelled – recently revealed that its RAFTI refuelling ports, used as a docking mechanism to transfer propellant, have qualified for flight and will be sold for US$30,000 per unit. The first spacecraft equipped with ports are expected to launch in 2025 for a refuelling demonstration.