Hollywood’s disaster movie genre has long been keen on the theme of the Earth being threatened by the imminent impact of a large object – usually an asteroid – from space. Examples include Meteor (1979), Armageddon (1998) and Deep Impact (1998). In the movies, the Earth is usually saved either by astronaut-placed nuclear explosions on the threatening object, or via a massed launch of nuclear-tipped missiles. However, there is another way if enough warning is given: deflection.

And that is why NASA launched its US$330 million DART – Double Asteroid Redirection Test – mission on board a Falcon 9 v1.2 Block 5 rocket at 0621 GMT from the Vandenberg launch site in California. The 500 kg DART spacecraft will make a 10-month voyage to the “asteroid moon” Dimorphos, which orbits another asteroid Didymos, before crashing into it at a closing velocity of circa 6 km/s in September 2022. The Falcon 9 reusable first stage B1063 landed successfully down range on the drone ship Of Course I Still Love You.

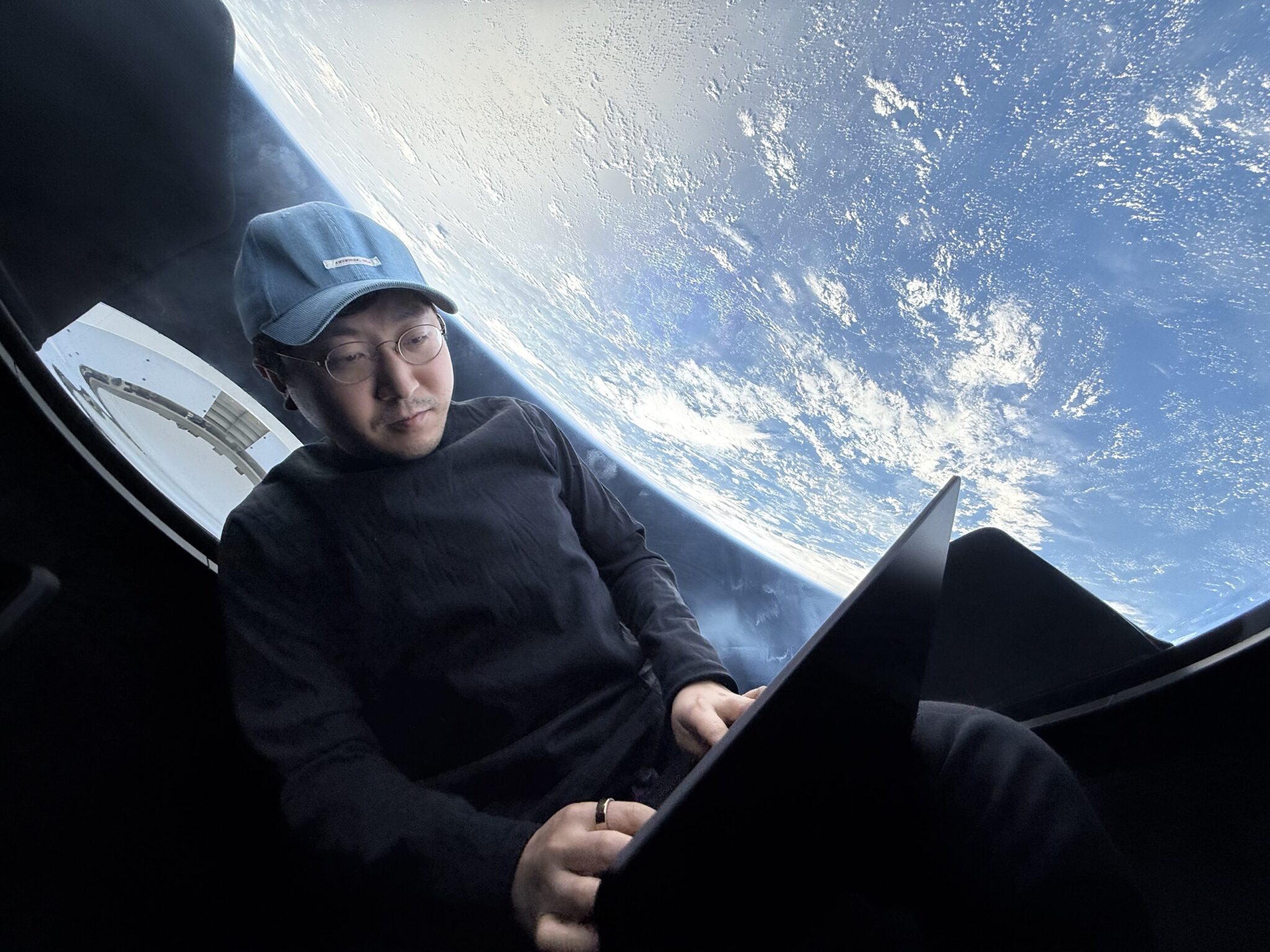

Artist’s impression of DART approaching asteroid before strike. Courtesy: NASA/Johns Hopkins-APL Steve Gribben

The DART spacecraft’s mass is miniscule relative to the 1 million metric ton class object it is striking, but combined with its very high velocity, it should be able to transfer enough momentum to change the trajectory of the Dimorphos body. The resulting delta V (change in velocity) will only be of the order of about 3 mm per second, but this will be enough to change the orbital period of Dimorphos around Didymos by about 2 per cent. The DART spacecraft is carrying the Liciacube satellite, which is to be deployed around 10 days before the collision so that it can image the event and its aftermath.

It should be noted that Dimorphos is in no way threatening planet Earth, nor is there any risk of the asteroid being moved towards it. After the impact a careful study of the trajectory will prove (or not) whether the deflection technology has worked. The idea is, of course, that if an asteroid threatened Earth it could have its trajectory changed in a similar way.

Comment by David Todd: If this experiment works, the technology will provide humankind with the means to potentially save the planet. There is one downside, however: the technology needs plenty of notice. To give it, astronomers need to map space objects continuously – usually photographically – in order to detect and track any that are moving towards Earth. This process is further complicated by the increasing number of spacecraft being launched – especially the large-scale low Earth orbit constellations such as SpaceX’s Starlink et al.