“Miss him dearly” was the touching comment that former Apollo 11 astronaut Mike Collins made on Twitter on what would have been his Apollo 11 commander late Neil Armstrong’s 90th birthday on 5 August. The Armstrong Air and Space Museum in Armstrong’s home town of Wapakoneta, Ohio, which celebrates his life, has recently refurbished the Douglas F-5D-1 Skylancer fighter jet which he flew in his time as a NASA test pilot. The museum originally had the jet loaned to it and then later donated to it by NASA. For several years it was outside of the museum as a “gate guardian”, suffering all that the weather and air pollution could throw at it. Now fully restored, it has joined the Gemini 8 space capsule he flew in, inside the museum.

Never heard of this aircraft? Well, the F-5D Skylancer was one of those very promising aircraft that became, due to politics and other competitor aircraft a “nearly bird” – that is one that was nearly taken into production but never quite made it.

Armstrong’s F-5D Skylancer test jet before its restoration. Courtesy: Armstrong Air and Space Museum

The Douglas F-5D Skylancer was a development of the Ed Heinemann-designed F-4D – no not a version of the famous F-4 Phantom II jet – but the “bat winged” F-4D Skyray aka “The Ford”. While the F-4D Skyray was not supersonic and had notable aerodynamic problems with “Mach tuck”, nevertheless, it excelled in climb and held the world record for a time. And it was this excellent steep climb performance which led to its being selected as the first “Stage Zero” for an air launched small launch vehicle NOTS-Pilot EV2 dubbed NOTSNIK), although none of the NOTS-Pilot Project’s six orbital launch attempts was ever fully confirmed as being successful.

Back to the story. The follow-on F-5D Skylancer was powered by the J57 jet engine and had a design which fixed the handling faults of its predecessor. It was fully supersonic with Mach 1.2 demonstrated but thought capable of reaching up to Mach 1.5. The plan was to make it fully Mach 2 capable by using the more powerful J79 turbojet with revised inlets. However, this never happened.

The US Navy rejected this promising jet fighter (just four were made in the J57 powered guise) after Mercury and Apollo astronaut-to-be US Navy test pilot, Alan B. Shepard, rejected the aircraft, noting in his report’s recommendations to the US Navy that it already had the already successful Mach 1.8-capable Vought F-8 Crusader as its supersonic single-seater fighter. By the way, it has to be noted that the F-8 Crusader subsequently excelled at Mig-killing in the later Vietnam war, making up for the US Navy’s more cumbersome two-seat F-4 Phantom II fighter’s lack of agility or guns. While Shepard’s argument might have been right, there were suggestions that political fears that Douglas was beginning to dominate naval jet aviation (Douglas already won the US Navy A-4 Skyhawk attack aircraft contract) were at play. By the way, the demise of the F-5D Skylancer was not the only potentially excellent supersonic jet to go down in this way: a similar proposal for the J-79 re-engining of the Grumman F-11F-1F Tiger to make it bi-sonic met the same fate.

Nevertheless, while the programme ended, the two surviving F-5D-1 jets (one other was lost and another grounded) did find a use as chase planes and test vehicles at NASA. It was at this point that Neil Armstrong – not yet a Gemini or Apollo moon walking astronaut – came into contact with it in his test pilot role. For while Armstrong test pilot career more is more remembered for his flights in the X-15 hypersonic rocket plane, he was also charged with using the F-5D-1 to test out a new launch abort concept.

During the early 1960s, the US Air Force was developing a revolutionary Titan III-launched mini-shuttle craft called the Boeing X-20 Dyna-soar. It was Armstrong’s job to test out these emergency escape scenarios with the F-5D-1 (the NASA 802 aircraft) as it was the closest jet in shape and handling characteristics. By the way, Armstrong was one of the test pilots secretly selected to be astronauts on test flights of the Dyna-Soar.

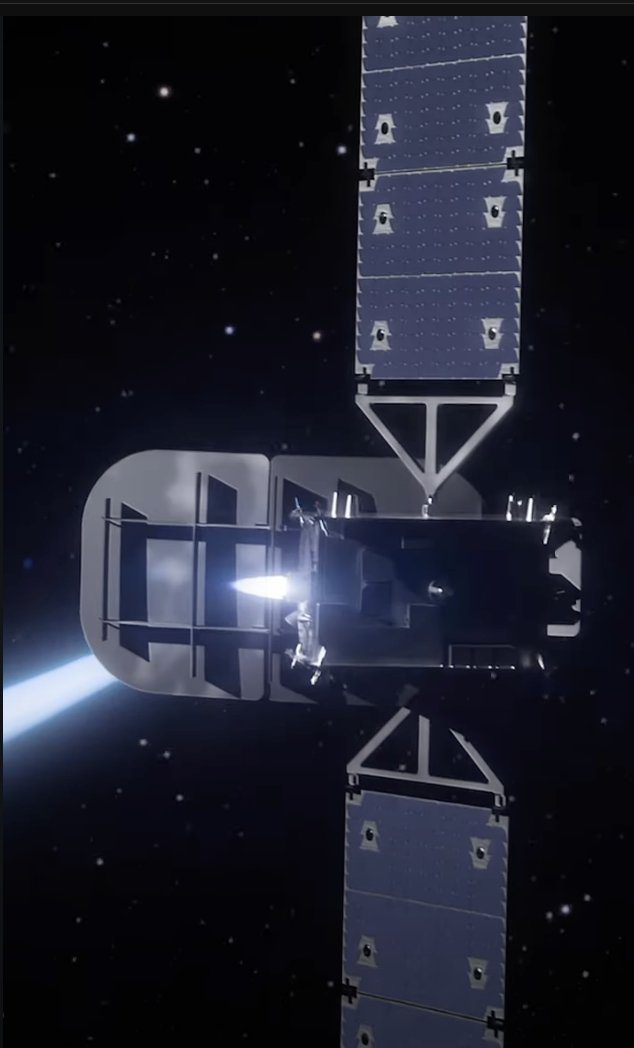

Artist’s illustration showing Dyna-Soar being launched on a Titan III. Courtesy: US Air Force via drewexmachina

The idea was that a escape rocket on the astronaut piloted Dyna-Soar craft would boost it away from the rest of the rocket in an emergency which would then be able glide to a safe landing.

At Edwards Air Force base in California, Armstrong mimicked this launch and escape procedure in the F-5D by making a zoom vertical climb from 200 feet to circa 8,000 feet followed by a pull over onto its back. He then correcting this upside down attitude via a half roll in a style of the famous World War I fighter pilot Max Immelman, followed by a steep glide back to Rogers Dry Lake for a landing.

In the end, successful though these tests were, the Dyna-Soar project was later cancelled in 1963 for being too technically ambitious and not having an adequate enough mission goal to justify its cost. Armstrong himself subsequently joined NASA’s astronaut corps proper later that year.

And the rest, as they say, is history – and one now celebrated in an Ohio museum.