The Artemis Accords are a set of guidelines for “responsible behaviour in space” drafted by NASA and the US Department of State. As implied by its name, the Accords are specifically about NASA’s Artemis programme: the US effort to return people – including the first woman – to the Moon, and further exploration of Mars. In theory the Artemis Accords simply set out principles for the peaceful use and exploration of the Moon. However, crucially, countries that want to book their astronaut a ride to the Moon on NASA’s Artemis lunar programme have to accept the Accords first.

China has its own lunar base programme which has also attracted significant international support – again in the hope that its signatories will get their astronauts to the Moon. In effect, this project is the competitor to Project Artemis and its accords. So how are the two sides progressing? Farah Ghouri analyses which one is ahead.

Artemis

At the second annual Artemis Accords meeting, representatives from 25 of the then 40 signatory nations gathered in Quebec, Canada, on 21 May to discuss principles for safe, transparent and sustainable space exploration. The guidelines emphasise transparency between countries (such as the publishing of scientific data to the public) and sustainable practices in space (including the preservation of “outer space heritage”). So far, so uncontroversial.

The proposed “safety zones” around Moon bases to prevent interference from rival countries or companies operating on the lunar surface receive less attention despite being a contentious part of the guidelines. The first mention of the Accords in mainstream media came in an exclusive by Reuters in March 2020. In it, the Accords were described by sources as “a legal blueprint for mining on the moon”. Indeed, they include a clause allowing companies to own the resources they mine under international law. It reads: “Signatories affirm that the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, and that contracts and other legal instruments relating to space resources should be consistent with that Treaty”.

When NASA publicly announced the Artemis Accords in 2020, it described them as the first step to establishing a coalition of “like-minded partners”. These partners were initially seven other founding member nations, alongside the US:

- Australia

- Canada

- Italy

- Japan

- Luxembourg

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

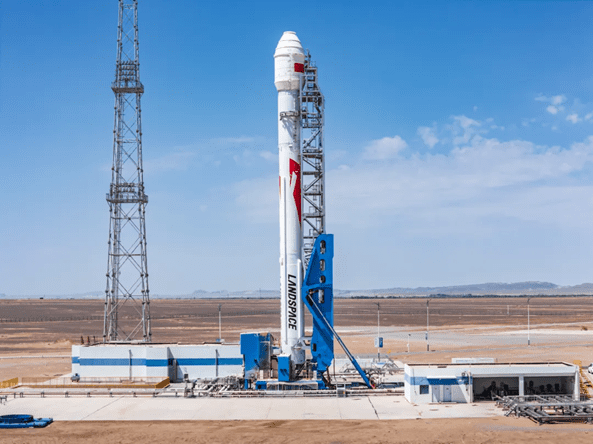

China’s International Lunar Research Station

Conspicuously missing from the inauguration of NASA’s new space club was Russia, its key collaborator on the International Space Station, and China. Dmitry Rogozin, director general of Roscosmos, called NASA’s Artemis lunar exploration programme too “US-centric” during a panel at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in October 2020, while China declared the Accords redundant given the existence of the legally binding 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST) and the 1979 Moon Agreement. It viewed the Accords as an attempt by the US to bypass legal systems for its own gain. Chinese state media went so far as to call the Accords “akin to European colonial enclosure land-taking methods”.

Less than a year later China and Russia announced plans for an International Lunar Research Station, or the ILRS, on the Moon. The project to construct a permanent lunar base is, much like the Artemis Accords, billed as “open to all interested countries and international partners”. Both the Accords and the ILRS revolve around exploration of the Moon and include guidelines for the activities undertaken. These include permanent installations, mining and use of Lunar resources, as well as manufacturing on the Moon.

Since the start of the year, nine countries have signed the Accords and another seven have signed up to the ILRS project (as of 31 May). The Artemis Accords are also faring better in terms total headcount: a total of 42 countries have agreed to the terms as established in 2020, while only 14 have signed the ILRS agreement as partners.

Notably, no country has yet signed up to both the Artemis Accords and the ILRS project, magnifying the growing chasm between the US and its rivals. A further 144 countries have not signed either agreement and are still to play for.