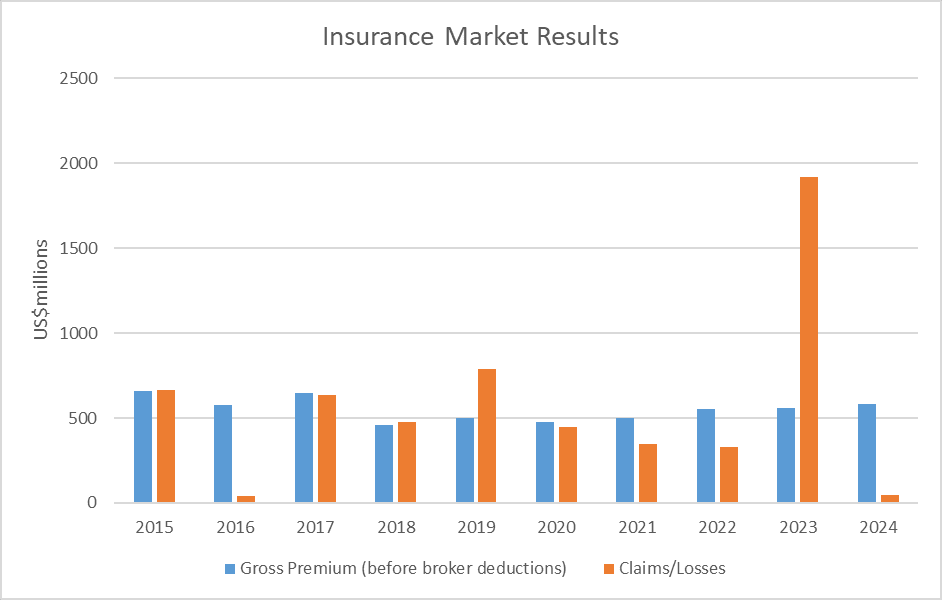

Although the 2024 calendar year proved to be a highly profitable one for space insurers, the industry continued to reel from a revised US$1.3 billion net loss for 2023.

Of the losses in 2023, most were relatively small sub-US$30 million claims. It was a series of significant high-value claims that inflated the overall total. Seradata initially assigned some of these losses to 2024. However, it was only later revealed to Seradata that although these were announced during 2024, they had occurred the year before. Once this was factored in, 2023 became the worst year ever in terms of overall result for the insurance market.

The first of the major losses involved the first four SES O3b mPower satellites (launched in pairs in December 2022 and April 2023 respectively). Both pairs suffered intermittent power disturbances that affected the payloads. An investigation into the incident later revealed the cause to be an electrical issue that was worse than initially thought. The result was a claim for a major partial loss (around 70%) covering all four spacecraft, and equating to US$472 million. Next came a US$445 million claim for the faulty deployment of the main Ka-band antenna of theViasat-3 Americas, launched in May 2023.

Other beams/antennas figured into some of the largest losses. These included a major anomaly involving the SkyTerra-1 satellite, which suffered an anomaly in orbit that affected its antenna reflector, resulting in degraded performance. An insurance claim for a constructive total loss of US$175 million was made.

A US$44 million claim for the solar array drive issues that affected Arcturus (Aurora 4A) was small beer after that.

Inmarsat’s unblemished insurance record – the company had not made a single claim in its history –looked to be under threat when its Inmarsat 6-F2 communications satellite became the subject of a total loss claim for US$348 million following a power subsystem anomaly and permanent battery failure. This may have originated with a Perseid meteor strike. The claim was the first for one of its satellites, but it came shortly after the company’s acquisition by Viasat. In other words, Inmarsat’s perfect insurance record remained intact as this was classified as a Viasat claim.

Late major claims in 2023 included a US$218 million claim for faulty antenna deployments on the SARah-Passiv 1 & 2 satellites (some sources say that these were split between December 2023 and January 2024). The final major loss of the year was for the failure of the communications payload on EDRS-C (Hylas 3) amounting to a US$60 million loss, industry officials told Seradata.

The total result for claims and losses on a calendar basis was nearly US$1.9 million. Set against this was the total gross premium income of around US$557 million – a loss ratio of more than 300%. In other words, 30 or so underwriting firms suffered a market loss of US$1.3 billion.

Although all space underwriters had a losing year, the losses were not evenly distributed with some underwriters nursing wounds from loss ratios of well above 300%.

What happened in 2024?

Date revisions dramatically reduced insurance claims for 2024 to around US$50 million. According to multiple insurance sources the remaining expected claims for 2024 include two in-orbit failures on:

– EROS C3-1, involving a propulsion issue which is likely to result in a partial insurance loss of around US$20-30 million;

– an unidentified spacecraft, with the claim estimated to reach US$15 million.

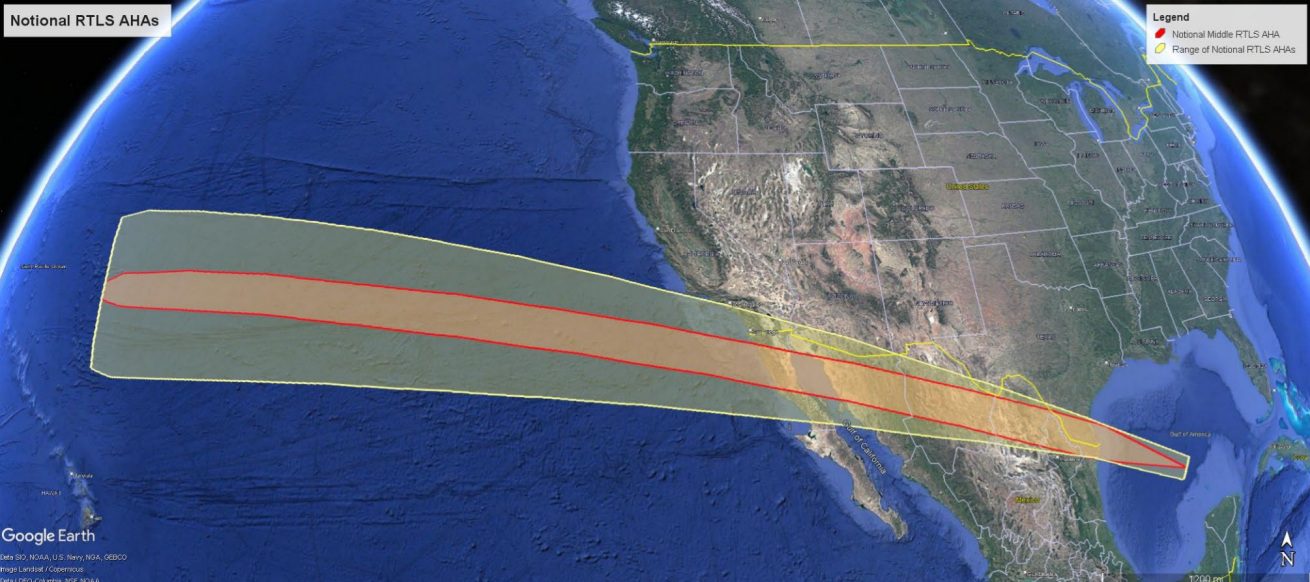

In addition, there was a launch failure of Lijian-1/Zhongke ZK-1A (Kinetica-1) on 27 December. It carried 11 small spacecraft, all of which were lost. Seradata understands that some of these were insured on the Chinese market up to a value of 50 million Yuan (US$6.8m). Against this was a premium of $580 million. In other words, it was a profitable year.

The problem for the space insurance market is that it will need a further three years with performances as good as 2024, for it to pay back the losses it incurred during 2023.

As a result of the market’s poor performance, capacity has fallen and premium rates have shown marked rises. However, a low number of insured launches means that the total level of gross premium is unlikely to grow significantly this year, with estimates of around US$570 million expected.

Premium rates

While each insurer will use its discretion to set the premium rate for its portion of a risk, every year Slingshot Seradata Intelligence surveys underwriters to find out what a ‘standard’ rate is for a given launch or in-orbit risk. These are quoted assuming that a typical spacecraft is carried. For example, the payload for a launch vehicle like Falcon 9 would be a satellite built by an experienced western or Japanese manufacturer, with good heritage and redundancy margins. For a Chinese launch vehicle, it would probably carry a Chinese-made spacecraft.

Some launch vehicles command higher premiums based on the type of spacecraft that they carry. For example, Earth Observation (EO) spacecraft traditionally have higher rates for the first year in orbit than communications satellites because the former are more prone to becoming total losses. Individual risks can have a major effect on the average and on trends where not many risks are placed. Likewise, a perceived increase in risk on a satellite might raise the rate for launch plus-one-year (L+1) but the launch vehicle flight (LVF) rate might fall.

Seradata clients can access this information via our Space Insurance Trends report on the Documents section of the database.

For some of the more reliable rockets, such as the ‘industry standard’ Falcon 9, premium rates have started to stabilise for LVF. In some cases, they have even fallen. However, most still have increasing LVF rates. L+1 rates have risen rapidly for all. Annual in-orbit insurance rates have also gone up significantly for GEO communications satellites. Underwriters have realised that the spacecraft element of the risk has been rated too low in the past.

The time-lag effect of rate rises, along with a relatively low number of insured launches in 2024 (caused by delays and few insured spacecraft), means that premium income overall has not increased significantly. In fact, it remains in the US$500-600 million region where it has been for the last five years, although it should start to rise as rate rises filter through.

Conclusion: withdrawals, job losses and office closures

As a result of the losses, many insurance companies are withdrawing from the space insurance class – a trend that started with the withdrawal of Swiss Re in 2019. In 2024, Canopius withdrew from the class, as did long-time space insurer Hiscox. The London branch of Munich Re has shut its space insurance doors as has the Paris office of the Dubai-based elseco. The significance of this is that an already low capacity – the amount of a risk in dollars that can be insured by the market – will be reduced in future. While theoretical capacity may still be above US$500 million, underwriters rarely risk more than half their theoretical maximum. Thus, brokers will probably struggle to place insurance for any risk above US$250 million, hence the rise in premium rates.

With respect to the market, space insurance income is not growing in line with the space industry. Whereas some LEO constellation operators in the growth sector of space will insure their launches, they rarely insure for in-orbit risk. GEO communications satellites and EO satellites remain the main insured set. The former is relatively flat, while growth in the latter is still quite limited.