While this writer was both an organiser and participant at the Seradata Space Conference in London in June, he can just about stay neutral enough to write about the event. Following a slightly doom-laden introduction about the prospects for space insurance, by Chairman Pascal Lecointe of Hiscox, the conference kicked off with a panel of new launch providers, moderated by Peter de Selding, of SpaceIntelreport. Tim Fuller, Managing Director of Seradata, presented the key launch trends, including that China is now the number one country for Space launches. He also noted that smaller satellites, especially cubesats, had become ubiquitous.

This was underlined by Abe Bonnema, of the satellite manufacturer and launch broker ISIS. He saw a move from the very smallest cubesats to slightly larger ones and regarded 20 kg as the new optimum, with software defined satellite systems becoming a key spacecraft technology.

When it came to picking launches, Bonnema noted the tension between customers wanting the lowest launch prices and needing to get their goods into orbit. “We want the highest credibility for the lowest prices,” he said.

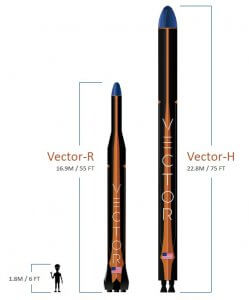

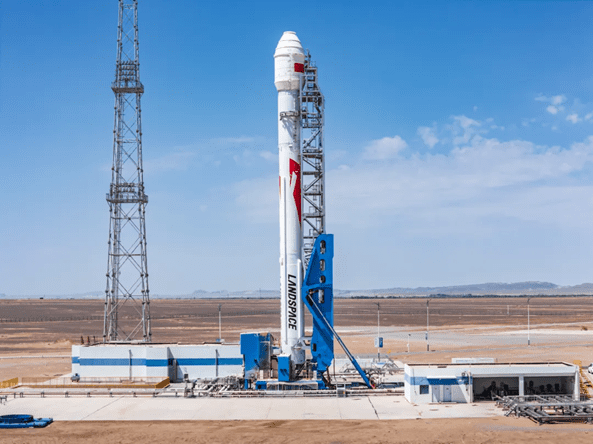

Four imminent entrants to the launch market were mainly in the small to medium class, including Vector, Firefly, Orbex and ABL. All were keen to show how that their programmes were not just “paper projects” – even if none had flown orbitally yet.

Vector’s Joseph Sasso proudly announced that its initial Vector-R launch vehicle would only have 900 parts – less than an average car. Orbex plans to use this rocket as a test bed for key technologies, including using chilled propylene with liquid oxygen (LOx) as propellants for a larger rocket called the Vector-H, which can launch up to 200 kg to a Sun-synchronous low Earth orbit. Sasso explained that it would take 100 Vector flights to produce as much pollution as a single Boeing 737 airliner flight.

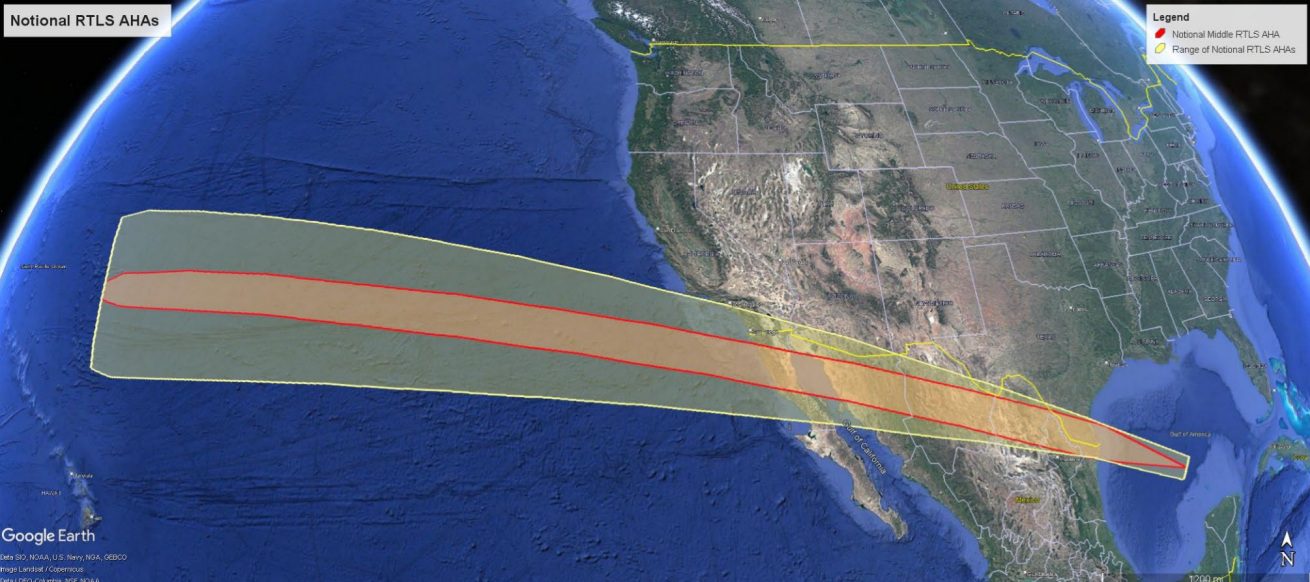

The Vector-R is due to make its first flight from Kodiak Island in Alaska in Q3 2019. Sasso had one complaint. His rocket would use several different launch sites (Kodiak Island, Wallops Island (MARS), Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg) and each tended to have a different set of regulations, especially in regard to the use of automated flight termination systems.

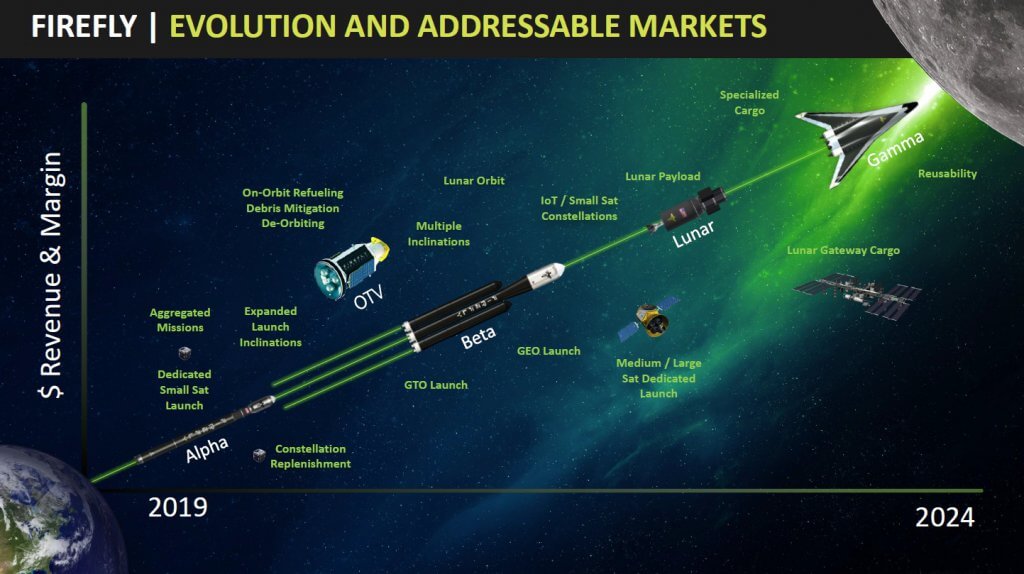

Eric Salwan described his Firefly firm’s Alpha rocket’s very efficient LOx/RP-1 Kerosene powered engine tap-off cycle, which gave it a performance advantage over engines using gas generators. Salwan noted that his firm expected to break even on just four launches per year and plans to offer lunar flights in conjunction with NASA’S Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, employing its upgraded Beta vehicle. Salwan intrigued the audience with one of his slides, which showed the reusable horizontal take-off space plane that his firm eventually hopes to produce.

Like Vector, Jan Skolmli, of UK-based Orbex, was keen to note how green its rockets would be. The LOx/Bio-LPG propellant combination would still allow the rocket to put 155 kg into a Sun-synchronous low Earth orbit from the Sutherland spaceport in Scotland. Doubts remain about insuring the flightpath, however. Even with a dog leg, it still passes over several high-value oil rigs.

Firefly’s long range plans include lunar missions and a horizontal take off space plane. Courtesy: Firefly

ABL, of the US, is a relatively unknown launch firm but has borrowed from the expertise of others with several operatives being ex-SpaceX employees. Dan Piemont noted that the planned largest constellations for low Earth orbit, e.g. OneWeb, SpaceX and Amazon, would amount to a need to launch 17,800 satellites by 2026…plenty to go around for many launch providers. ABL hopes to fly its LOx/JET-A1 Kerosene gas generator powered RS-1 rocket in Q3 2020. That rocket can get small 400 kg satellites into a geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO) and can even get 200 kg to the Moon.

Getting it to work in orbit

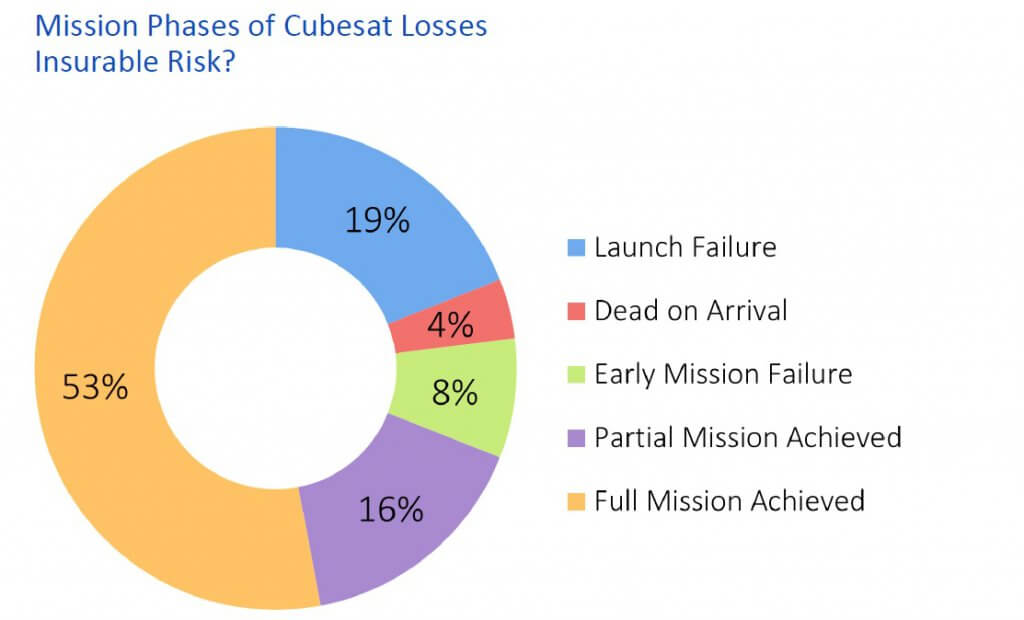

Of course, putting your satellites into orbit is one thing, but getting them to work there is another. Jan Schmidt, of underwriter Swiss Re, reported that up to half of all CubeSat class satellites failed or suffered partial failure either during the launch phase or early in orbit, making them a very unattractive proposition to insure. (Author’s Comment: while we agree that the failure rate is high, this figure is significantly higher than the circa 17% we have on the Seradata database for launch plus one year, with launch and in-orbit anomalies causing a capability loss of more than 10 per cent).

CubeSats are very prone to failure. Courtesy: Swiss Re Original Sources: IUAI/AXA XL/Aerospace Corp. MAIW Report TOR

2017 01689

Many believe there will be a market for large communications and Earth observation satellite constellations in low Earth orbit. However, Mark Boggett, of finance house Seraphim, warned that exponential growth in the space industry might yet be tempered by the “choke point” problem of getting so much data back to the ground via down links. Still, he predicted that space would become a key growth sector, citing how one of the space firms he has invested in, Altitude Angel, is trying to use spacecraft to solve the problem of drone incursions and the drone threat to aircraft, via a space-based geo-fencing solution.

Boggett warned that some space technologies would have serious implications for human activity. Specifically, he noted that Quantum Computers and communications would render past security systems redundant.

Making small satellites is the business of GomSpace. Emilie Marlie Siemsen, its legal counsel, amused many by revealing that the Aarlborg-based firm’s name surprisingly stands for “Grumpy Old Men” Space. Ms Siemsen said that while there was a minimum in-orbit liability insurance cover requirement of €60 million, this amount was not formally defined as per satellite or per occurrence. However, she said that by working with insurance brokers the firm had come up with an insurance product that would cover the per occurrence eventuality.

Iceye is planning a constellation of 18 miniature radar satellites (six by next year), which would allow a three-hour revisit time anywhere on earth. Such an observation system, whether used for security or even flood tracking, would not be hindered by night or cloud. Iceye’s Matti Ekdanni explained that operators would need launch and third-party liability insurance but would not need in-orbit insurance (constellations would have spare satellites). In a way, this suits underwriters who remain less keen on having long-term exposure to launch-scale, assembly line manufactured spacecraft, on which a generic fault might only become obvious after many satellites have been launched.

It was generally accepted that mass produced, lower-cost spacecraft would be less reliable than their more bespoke and longer tested high-cost counterparts. Cost is king, said James Spencer, of TT Electronics, implying that reliability would inevitably fall, with the further complication that as satellite size reduced, electronics density would go up. Spencer said that while the extensive testing of spacecraft might be a thing of the past, there should still be a role for custom qualification of parts.

Blue Origin thinks that GEO will survive while Intelsat looks forward to satellite role in 5G

Keynote speaker Clay Mowry, of Blue Origin, expressed optimism about the GEO satellite launch market and predicted that GEO satellites would continue to have a role in mobile communications. He also reported on Blue Origin’s testing of its human-carrying New Shepard suborbital rocket and gave an update on planned tests of the New Glenn orbital rocket and on the development of the Blue Moon lunar lander.

Clay Mowry describes the progress on Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket. Courtesy: Seradata/Elspeth Fuller

With respect to Blue Origin’s lunar exploration plans, he refused to be drawn on whether Blue Origin would build an even larger launch vehicle than New Glenn, unofficially dubbed New Armstrong. Nevertheless, he gave a hint by confirming that “New Glenn is the smallest orbital launch vehicle that we will ever build”.

Greg Ewart, of Intelsat, pointed to the huge cost of rolling out a purely terrestrial infrastructure for the new 5G standard in telecommunications. He expected a definite role for satellite constellations. Ewart reiterated a point made earlier in the conference that software-defined systems including satellite software-defined communications payloads would be key in the 5G environment.

Insurance Pow-Wow: Insurers keep their nerve and look forward to “new space”

Stefane Rives, of Scor, set the challenging scene for the insurance panel in the context of insurance losses and falling rates, albeit with increasing numbers of insured launches. Cunningly, he elected to leave it to the panel to debate the solutions.

On the key question of whether the market will repeat last year’s loss-making result, the panel and the audience (on balance) still managed to be positive. However, Peter Elson, of the broker Gallaghers, reminded the panel that other classes of insurance had rising rates and so space remained out of step. Would this reduce capital and capacity in the space insurance market? Only time would tell.

Insurance Pow-wow Panel: Jeff Poliseno (Aon), Russell Sawyer (Willis Towers Watson) Adam Sturmer (Marsh), Peter Elson (Gallaghers), Chris Kunstadter (AXA XL), Devin Fairbanks (Starr Aviation), Laurent Esquirol (Tokio Marine Kiln), and Tim Wakeman (elseco) with David Todd (Seradata) as moderator. Courtesy: Seradata/Elspeth Fuller

As premium rates and geostationary satellite launches (and hence premium revenues) have fallen, underwriters have had to adjust to keep up premium income. They have been forced to accept past bêtes noires, including launch plus multi-year policies. Despite the payout for the mission failure of WorldView 4 in its middle years, Devin Fairbanks, underwriter at Starr Aviation, said that after making her own analysis she now supports these kind of policies. Russell Sawyer, of the broker Willis, reiterated that long-term post launch policies were popular with space operators…i.e. his clients.

Chris Kundstadter, long-time space underwriter at Axa XL, noted that for “new space”, the market would have the rating analysis capability to cover new launch vehicles and new small satellite technologies. However, he warned that small satellites – especially cubesats – remained very much a minor part of the insurance business in terms of premium revenue.

While the definition of what constitutes a “terrorist” is notoriously vague and often unfair – some regimes around the world tend to define all of their opponents as “terrorists” – as such, the notion that a teenage computer hacker is defined as a cyber terrorist still rankles with some. Thus Laurent Esquirol, underwriter at Tokio Marine Kiln, tried to make the case for a third way in terms of cyber protection in space insurance policies. But he looked a little taken aback when it was pointed out that most cyber-attacks were deliberate acts and, thus, should still be part of terrorism and war insurance rather than space insurance.

Tim Wakeman, of elesco, tried to be measured as he explained what “line slips” were (a method of bundling up risks in a managed way by brokers), but could not cover up his – and other underwriters’ – dislike of them. Their view is that this approach was invented by brokers to sew up cover at cheap rates in their clients’ interests.

Responding to an audience question on whether the vertical marketing concept should be ditched in favour of the old “lead underwriter and following market” set-up, the brokers seemed unanimous that the current system was best because competition benefited the clients in having proper premium rate competition. After the panel ended, Russell Sawyer, of Willis Towers Watson, said that while he was not an advocate of a “lead” setting the rate, he had wanted publicly to express his sympathy for those underwriters who were struggling to keep their expensive expertise alive in such a competitive market. A kindly space insurance broker…whatever next?! There may be a solution. During the panel, Elson suggested that underwriter expertise in technical analysis for some risks might be paid for via a fee arrangement.

Jeff Poliseno, of Aon, reminded the audience that while last year was a loss maker overall, some underwriters did better than others, whether by skill or luck. As to which space broker or underwriter was most admired in the market, the panel tried to be diplomatic. Nevertheless, the name of David Wade, of Atrium, kept coming up, embarrassing him in the process. Your correspondent has personal knowledge of David Wade’s skill and character – he used to help me with his homework when we were astronautics students at Cranfield many years ago!

Tracking and Liability: Identifying which satellite remains important…especially if in-orbit liability is to be judged

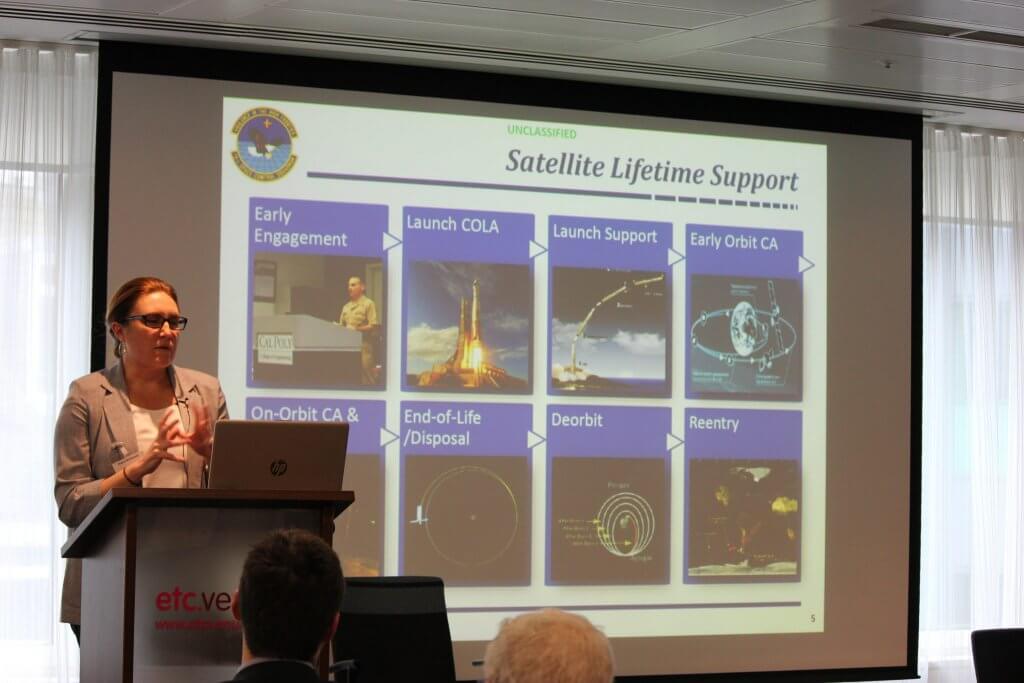

Diana McKissock, of US Space Command explained that she was not used to addressing an audience of commercial space and insurance types instead of US Colonels and Generals. She described how her organisation tracks space objects, noting that her main problem was assigning an identity once an object is tracked.

McKissock praised the growing cooperation between commercial entities and her organisation, as they all try to sort out which satellite is which. However, she acknowledged that some organisations could be less than forthcoming and complained, somewhat ruefully, that universities were surprisingly difficult to engage with.

New commercial ventures are now adding to the resources of US Space Command with their own detection systems. One of these is LeoLabs, which is constructing a network of six radar systems around the world. It hopes to complete these by the end of 2020. Matt Shoupe, of LeoLabs, said it hoped to track objects as small as 2 cm in low Earth orbit.

Moot court causes a few laughs but some serious thought

The subject of satellite servicing and how this might affect in-orbit liability was covered by a “Moot Court” in which a fictional company, Acme Satellite Servicing, found itself the defendant having accidentally destroyed its client’s satellite during its spacecraft’s attempted initial grapple, with debris from this also damaging a third satellite. Joanne Wheeler, managing partner of Alden, who has advised several servicing companies and the UK Space Agency, found herself in the role of a barrister as she defended Acme over the resulting insurance claims. She was opposed by Chris Newman, Professor of Space Law at Northumbria University, who was acting for the notional claimants. The arguments involved consideration of the launching state, consideration of who had the duty of care (the servicing company or its client) and whether it had been successfully applied, and whether the liability was, in truth, really “joint and several”. While not really considered, in a true servicing contract there would probably have been an agreed point of transition of responsibility between the client and the servicing company – probably at some time-line event such as he initial successful grapple itself. In this case, given that the grapple was not successful, this might have been vague anyway.

The Jury audience was split but NOT GUILTY (green thumbs up) just held off the red GUILTY thumbs downs for the ACME satellite servicing company. Courtesy: Seradata/Elspeth Fuller

In a close-run thing, the Acme Satellite Servicing company was found not guilty by the jury (the audience), shown via the thumbs up end of their voting rulers (thumbs down meant guilty). With Joanne awarded a bottle of Champagne as the winning counsel, your correspondent, in his judge’s garb, placed a black silk square on top of his wig to indicate the imminent pronouncement of a joke “death penalty” on the loser Chris Newman. Thankfully, in the end, his sentence was commuted to a “our very best wishes”.

Space lawyer Joanne Wheeler sees the funny side as Professor of Space Law Chris Newman sat next to her is given the notional/dummy “death penalty”. Courtesy: Seradata/Elspeth Fuller

Conclusion: Overall it was a successful conference and highly rated by attendees. Some hankered for a bit more fire and argument, especially in the insurance pow-pow. Others would have liked a few more satellite operators to be present. All appreciated that the proceedings were kept to time, thanks to a soccer-style yellow card (time warning) and red card (sent off) system as shown by the time adjudicator Sally Hylands. Mind you, she was amusingly harsh on her boss, Seradata’s Managing Director Tim Fuller (the founder of the Conference), by giving him a red card as soon as he stood up to speak.