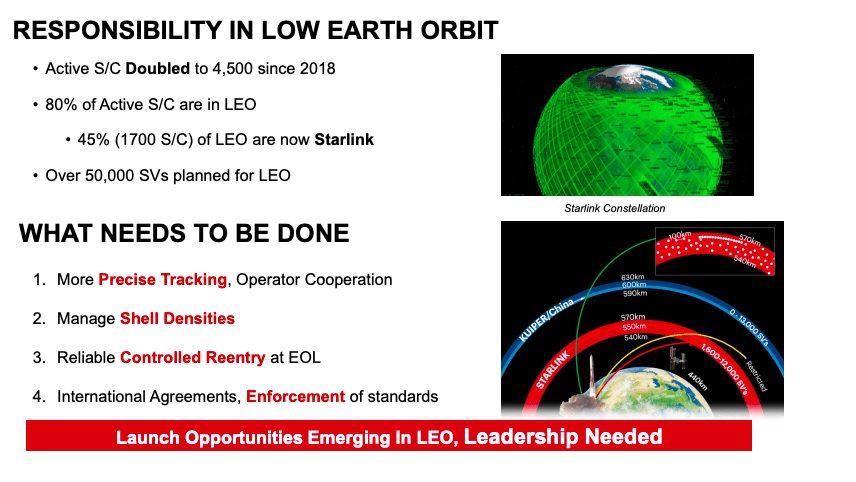

PARIS — The arrival of several mega-constellations in low Earth orbit, coupled with today’s imprecise satellite tracking, will make satellite collisions just as important as frequency interference in future licensing regimes, United Launch Alliance Chief Executive Tory Bruno said.

Even now, when SpaceX’s 4,400-satellite Starlink constellation is only half at 550 kilometers and other constellations near that orbit are yet to launch, launch providers need to make special preparations if they are carrying satellites whose destination is near the SpaceX Starlink altitude, he said.

“If you are going to a much higher [orbital] shell than the first mega-constellation that’s currently in orbit, and about half populated, you do not see a significant impact on your accessibility to fly through that because you’re flying through the shore direction, radially outward,” Bruno said June 24 at a space insurance conference organized by Seradata.

“If you were to fly to another LEO orbit that is just above [550 km], you are going to sweep a long, gradual arc through that shell. And when you do that, with today’s tools and the precision we can track, and criteria for collision avoidance, it is a significant reduction in launch opportunities — less chances to fly through that without risking a collision. It’s a big deal.”

Bruno was speaking of “proliferated LEO” constellations in general and was referring to SpaceX only because Starlink is the first mega constellation to conduct large-scale launches.

Others are coming, including Amazon’s Kuiper, which has selected ULA to conduct nine Atlas 5 rocket launches of Kuiper satellites under what ULA has said is a firm contract. Kuiper’s design is for 3,236 satellites operating near the SpaceX Starlink orbit.

This is why Amazon was among those companies asking U.S. regulators not to allow SpaceX to modify its earlier design, which had been licensed, to place all the satellites in a lower orbit.

“Other people cannot cohabit that orbital shell,” Bruno said of the Starlink orbit. “They’re full. That’s it. If you want to go to space and been LEO, you have to go to a different orbital shell now.”

Bruno’s point is not that SpaceX has an exclusive license to its orbit, but that the imprecision of today’s satellite tracking means any other satellite operator would need to include a margin of error by carving out a no-fly zone around each Starlink satellite to be sure to avoid collision. Once that is done, there is not much room left.

How other nations will react to this fact remains to be seen.

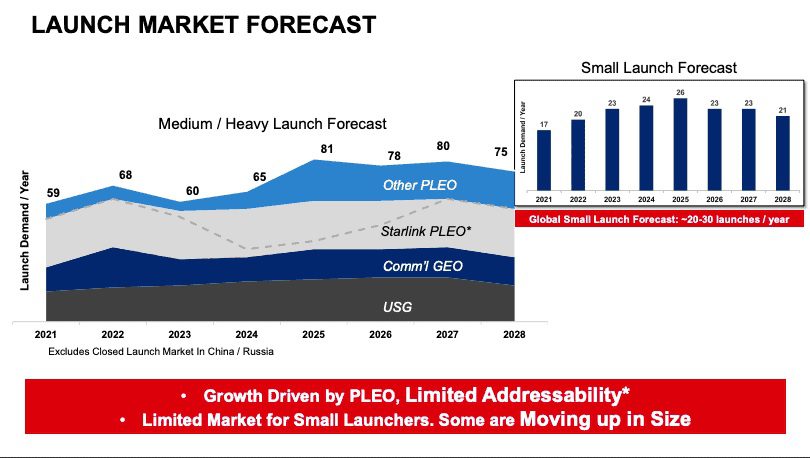

The dotted line in the Starlink PLEO accounts for the possibility that SpaceX will introduce a major technology refresh in the late 2020s. ULA thinks SpaceX’s Starlink launch rate will remain stable as new technology is introduced continuously. Courtest: ULA

Also part of the problem is what happens when, with several large constellations in operation, satellites being retired are drifting through LEO on their way to disintegrating in the Earth’s atmosphere.

“When there are many spacecraft per day that are reentering, those reentries need to be controlled so that the trajectories are steep and predictable,” he said.

Most of Bruno’s speech was devoted to ULA’s assessment of today’s global launch market an his company’s place in it.

ULA has not been active in the commercial market because of its pricing policy and the fact that it has not needed much commercial business to remain healthy.

The nine-launch Kuiper contract with Atlas 5, one of the most expensive commercial rockets, was due in part to the lack of availability of the Blue Origin New Glenn vehicle, still in development — Blue Origin is owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos — and the fact that Europe’s Ariane 5 inventory is being depleted as that vehicle retires in favor of Ariane 6, which will not be commercially available until 2023.

Whether ULA’s Vulcan rocket, scheduled to fly starting in 2022, will be more active in the non-U.S. government market is unclear.

Bruno outlined the global launch-services landscape and said multiple nations continue to view launch vehicles as key to their strategic autonomy. Most of these receive government subsidies that protect them from “the vagaries of the ups and downs of the market from year to year,” he said.

“It is unlikely we will ever have an under supply of launch, which means it is likely we will continue to have downward pressure on launch prices,” he said.

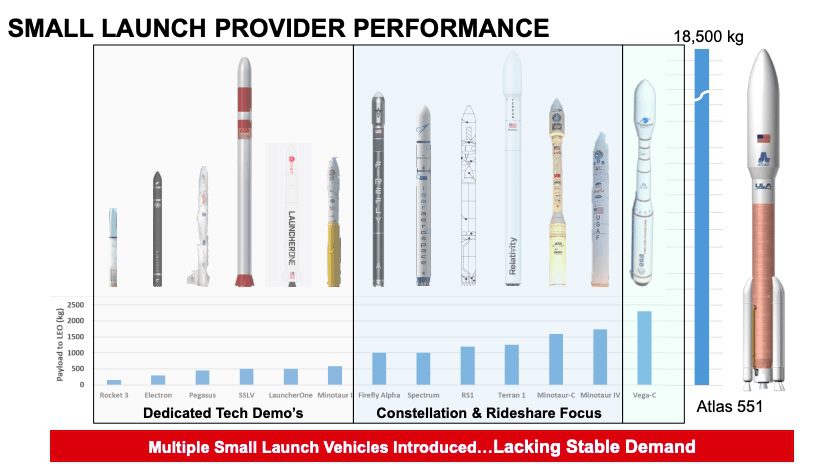

Bruno repeated what he and his counterparts at SpaceX and Europe’s Arianespace have said before, which is that few of the small launchers now in development are likely to survive given the advantage to constellation operators of launching large groups of satellites on big rockets.

Several of these small-launcher companies have said they will take advantage of the emerging market in replacing constellation satellites a few at a time in the event of satellite failures.

Except that… “One of the powers of a proliferated LEO constellation is that when it is fully populated, it is pretty insensitive to the loss of any individual satellite,” Bruno said.

ULA forecasts 20-30 launches of smaller vehicles per year, a stable cadence that leaves room for two, perhaps three players, he said.

This story first appeared in https://www.spaceintelreport.com/ and is reprinted with permission.