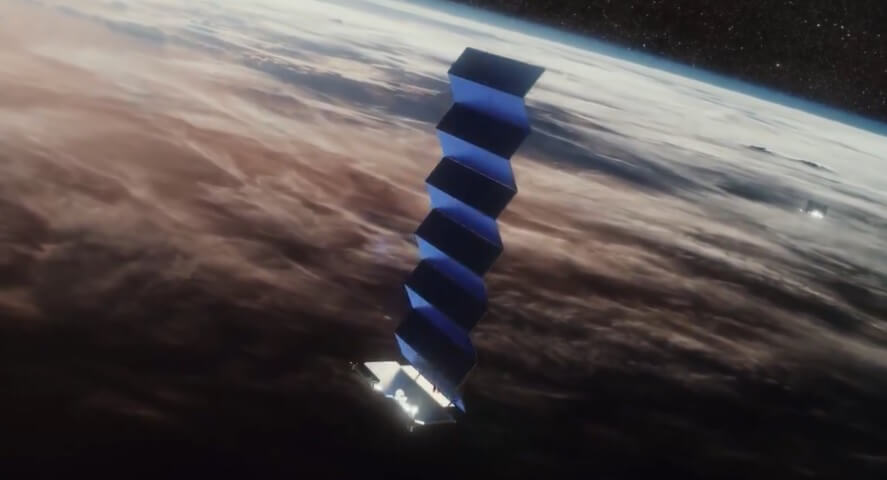

SpaceX has admitted a new blow to its Starlink low Earth orbit-based communications satellite constellation. There were already doubts about the reliability of the Starlink V1.0 satellites (about a quarter of the 60 satellites on a Falcon 9 launch in March last year failed), but worse news came with the latest launch. SpaceX has admitted that it lost control of 38 out of 49 satellites in its new laser-communications-equipped v1.5 version launched on 9 February. The cause of the latest failures has been attributed by SpaceX to a solar-induced geomagnetic storm the day after launch, rather than any generic faults on the spacecraft.

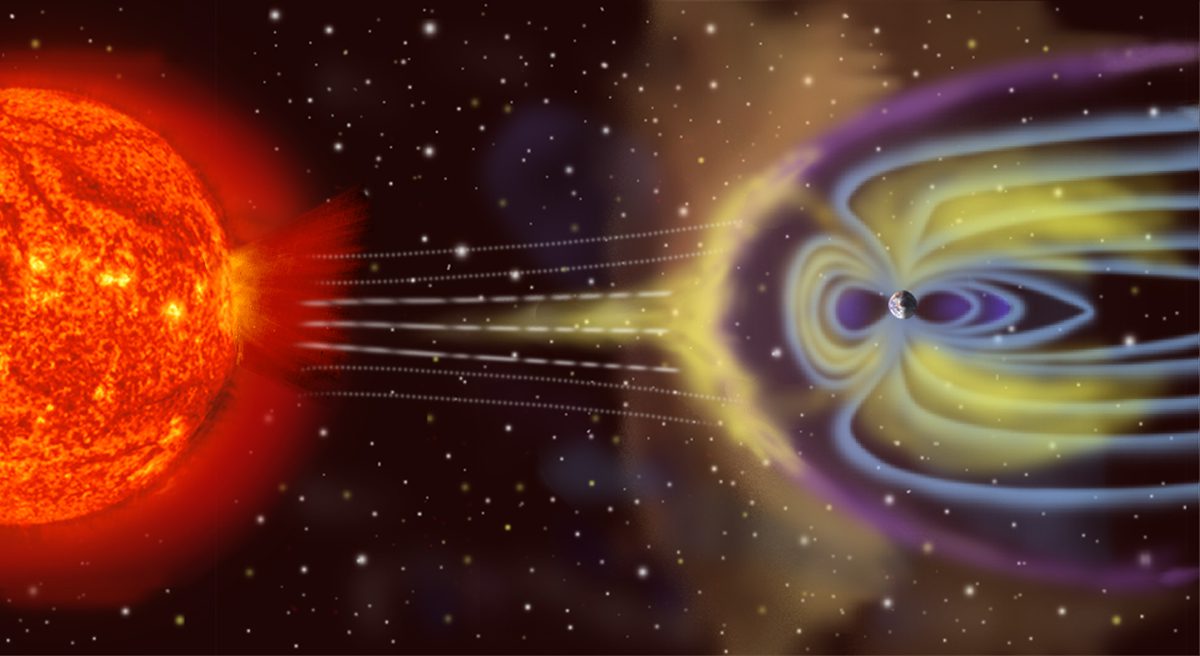

Solar event induced surges in the solar wind can compress the field lines of the Earth’s magnetic field. Courtesy: Wikipedia

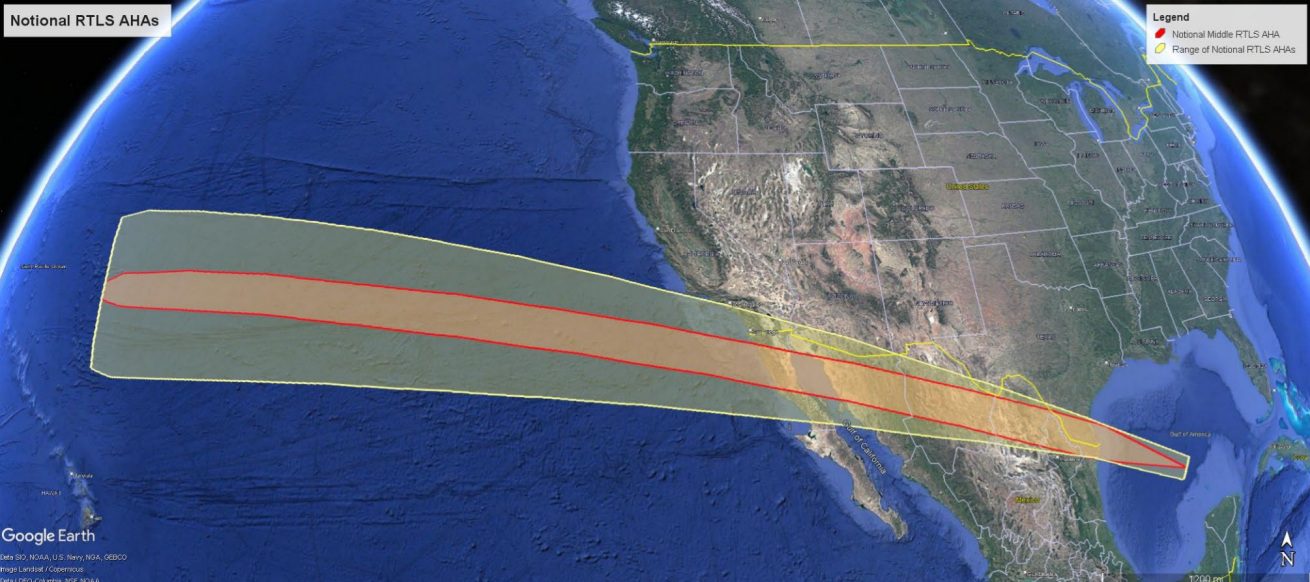

SpaceX claims that the increased drag caused by the geomagnetic storm – a secondary effect of such an event – resulted in the satellites being deliberately put into a “safe mode” to reduce their drag (they fly edge on to the flow in that state). They were later prevented from leaving their “safe mode” and so were unable to be controlled or to have their orbits raised. Analysts have warned that with this increased atmospheric drag, if the orbital perigee is not raised soon (the satellites were released into a circa 330 x 220 km orbit) the satellites will re-enter within days.

Update on 11 February: Five satellites from the launched batch have now been confirmed as having re-entered and it is believed that a further 34 had already re-entered before they were properly tracked and identified.

Geomagnetic storms occur when the field lines of the Earth’s magnetic field/magnetosphere are compressed, usually by a rush of charged particles in the solar wind. This is in turn caused by a solar coronal mass ejection or solar flare, or by a temporary connection with the sun’s magnetic field. The result can be increased charging of spacecraft by charged particles, causing electro-static discharges that damage hardware. On-board magnetometers and magnetorquers can be affected by changes in the Earth’s magnetic field, while charged particles can also cause “single event upsets” (SEU) and “bit flips”, which can affect computer circuitry and even control code on spacecraft. Most satellites use circuits and chips hardened against solar radiation and other electromagnetic disturbances, and often employ “Faraday Cages” to protect their most vulnerable parts against electrostatic discharges.

The increased solar activity also heats the Earth’s upper atmosphere – the thermosphere expands – and this becomes denser at low Earth orbital altitudes. This adds significantly to atmospheric drag, which, contrary to public perception, does exist in low Earth orbit. This effect on atmospheric drag was the reason why NASA’s first space station Skylab re-entered several years earlier than planned.

Due to the number of Starlink satellites SpaceX already has in orbit (according to the Seradata SpaceTrak database over 1,800 are active), which provide adequate overall constellation redundancy, SpaceX has elected not to have its launches or satellites covered by insurance.

Comment by David Todd: The official statement from SpaceX implies that increased atmospheric drag from the solar/geomagnetic event resulted in the loss of control of these satellites by not allowing them to leave safe mode. Their efficient electric Krypton ion thrusters, which are less powerful than equivalent Xenon types, may not have had enough thrust to cope with the increased drag itself. Further, the on-board attitude control magnetorquers/reaction wheels may not have been able to give the spacecraft enough control authority to turn the spacecraft in a higher drag environment.

Nevertheless, such a failure scenario would be highly unusual. When solar/geomagnetic events are cited as the underlying cause of the sudden deaths of satellites, electrostatic discharges or single event upsets are much more common mechanisms at work.

Whatever the case, the real question is: why only these Starlink v1.5 spacecraft were affected? Was it a mission design/deployment orbit error? It has been speculated that future launches may have Starlink satellites deployed into higher, less draggy initial orbits, albeit at the expense of carrying fewer satellites. Or was it an attitude control system design oversight to use ion engines with too little thrust, which did not allow for the increased drag? It may have been a combination of these factors. For example, the thrusters may have needed the power generating solar array to be in a high drag position. As such, the spacecraft may actually have been in a “Catch-22” situation: without enough thrust even in a low drag configuration to counter the drag or climb to a safe orbit, and yet to get enough thrust it needed a solar array orientation producing too much drag for the thrusters to cope with.

Update on 22 February: The subsequent Falcon 9 launch of Starlink v1.5 satellites (Group 4-8) carried three less spacecraft and was thus able to achieve a near circular 330 km orbit.