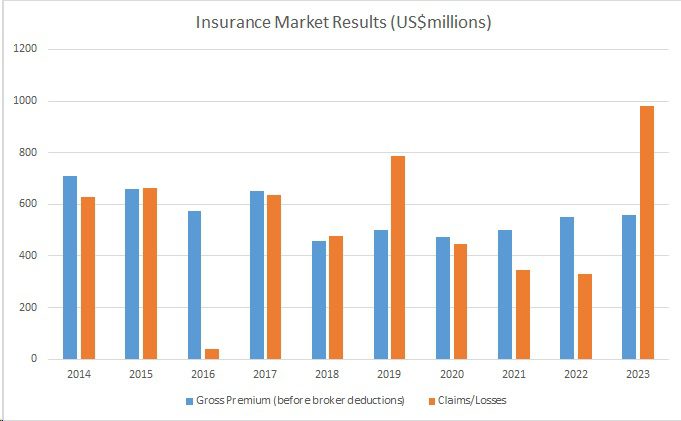

Space insurers are still licking their wounds after what has been the worst year in over two decades in terms of claims, with a total of close to US$1 billion for the industry. In the early part of the year there were few insurance losses and, although they received a lot of TV coverage, they were relatively small in terms of the claim values. For example, there were four small satellites on the Virgin Orbit LauncherOne launch failure all under US$1 million each. Likewise, the first large launch failure – Japan’s H3 maiden – only yielded a US$12 million for the loss of the ALOS spacecraft.

The first of the large losses was the US$445 million claim due to the faulty deployment of the main Ka-band antenna on Viasat-3 Americas. Inmarsat’s long and unblemished record, having never hitherto made an insurance claim, came to an abrupt end when its Inmarsat 6-F2 communications satellite became the subject of a total loss claim for US$348 million. It followed a battery failure which, it has been speculated, was initiated by a Perseid meteor strike. The timing was unfortunate in other ways too: Inmarsat’s first claim came swiftly on the heels of its acquisition by Viasat.

It may not end there as more claims are likely; specifically, from O3b mPOWER satellites, given their electrical issues – although these may fall in 2024 instead of 2023. With the final likely claim of the year – US$13.3 million for HotSat-1’s imager failure – the net result was that claims and losses totalled US$995 million. Set against this total was the total gross premium income of around US$557 million. The market is thus in major loss – even before broker deductions and running costs are taken into account.

Space Insurance Market results show a major net loss in 2023. Courtesy: Seradata/Industry Premium Estimates

By the end of the year, while a few ‘dodged the bullets’ by avoiding the worst of the claims, many space underwriters were nursing loss ratios of above 200 per cent. As a result, some underwriters are either removing themselves from the class, or severely restricting their available capacity. For example, the British syndicate, a successor to the Marham Consortium, which had a long-term participation in the space market left, withdrew its US$50 million capacity (the amount it could theoretically insure on a single risk). Not only direct insurers have been affected: reinsurance capacity is also expected to fall by a minimum of 50 per cent.

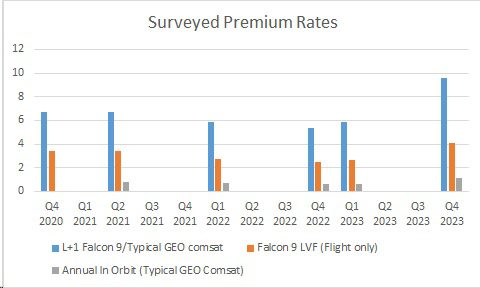

Space Insurance: Launch plus one and in orbit premium rates are rapidly rising. Courtesy: Seradata

Meanwhile, premium rates are markedly increasing, especially for the “plus one year” part of standard launch insurance (anomalies in the early part of life account for most of the major losses). For example, a typical GEO satellite aboard a Falcon 9 might have commanded a rate of under 6 per cent at the beginning of the year. Now it is not far short of 10 per cent. Annual in orbit insurance was similarly affected with a near doubling of rates from circa 0.6 per cent to close to 1.2 per cent.

The full space insurance report is available to subscribers on the documents section of the Seradata launch and spacecraft database.

Correction: The loss total was not the worst ever but the worst since 2001 – according to a calendar basis (date of premium revenue in and date of occurrence/loss date) which Seradata measures by. The 2000 year’s claims were US$1390 million (the worst year ever in terms of loss/claims total was 1998 with US$1803 million).

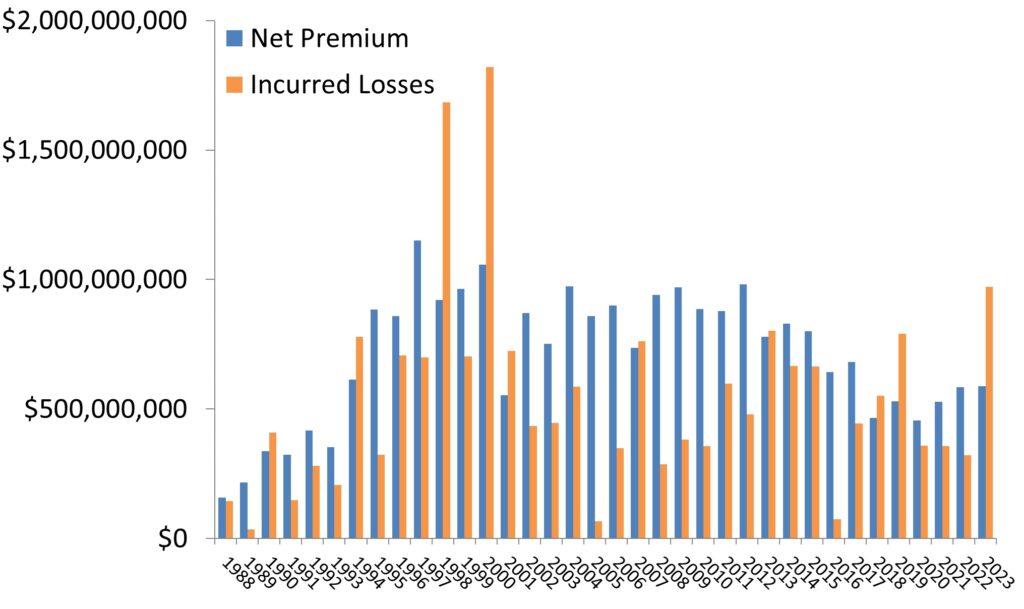

Note that underwriters sometimes account differently, putting in the premium and loss revenue in a given year according to the date of attachment of the insurance policy etc. AXA XL notes that 2000 was the worst year ever. Here below are the market insurance results according to AXA XL with net premium (premium after broker deductions) versus incurred losses in a given year.

Insurance market results according to AXA XL. Courtesy: AXA XL