Farah Ghouri and David Todd followed the launch, descent, landing and subsequent communications of the first private spacecraft lunar landing

“Odysseus is alive and well” was the first update on IM-1 from its operator after the lander touched down on the Moon, making Intuitive Machines the first private firm to achieve the feat. However, it only later revealed that IM-1 had not landed on its feet. It suffered a ‘crash landing’ instead, which saw it tip over and end up perpetually stuck on its side on the Moon.

IM-1 is the first of at least three robotic lunar landing missions by the Houston, Texas based firm. The missions are part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, which form a key part of the space agency’s Artemis lunar exploration plans.

Courtesy: Intuitive Machines

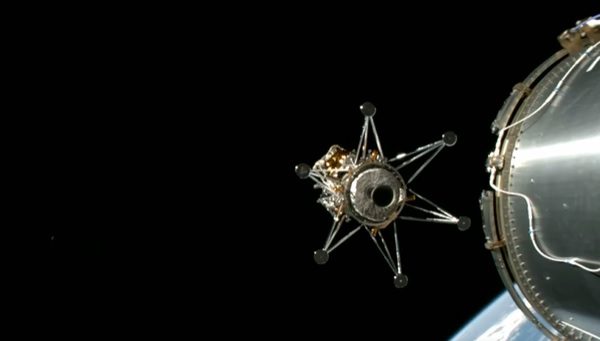

IM-1 set off on its journey to the Moon onboard a SpaceX Falcon 9v1.2FT Block 5 rocket. The launch took place from Kennedy Space Centre, USA at 0605 GMT on 15 February. The rocket’s B1060 first stage landed back at Kennedy Space Centre on Landing Zone 1. After making two course corrections, the lander entered orbit around the Moon on 21 February via a 408-second main engine lunar orbit insertion burn, putting it into a 92 km circular lunar orbit.

IM-1 Odysseus is released into its Trans Lunar trajectory by Falcon 9’s upper stage. Courtesy: SpaceX

It was originally planned that the spacecraft would reach the surface near the South Pole of the Moon on 23 February, but this landing attempt was brought forward by one day. The controllers were probably concerned that the main propulsion system uses a cryogenic liquid oxygen (LOX)/liquid methane propellant combination, which boils off over time.

A nail-biting ‘crash’ landing

The Nova-C bus IM-1 lander, also known as Odysseus or Odie for short, touched down on the lunar surface at 23:23 GMT on 22 February, about ten degrees north of the Lunar south pole. Intuitive Machines delayed the landing by two hours to make an additional orbit around the Moon after the laser range finder – used to measure altitude and velocity – failed. To get around this untimely hitch, two lasers aboard NASA’s Navigation Doppler Lidar were pressed into service using an uplinked software patch. As a direct result of the software change, the Embry-Riddle EagleCam landing observing cubesat was powered down. Its ‘pop out’ deployment, due to happen in the last stage of the landing, was delayed until 28 February, several days after its mother ship had landed. The late deployment of EagleCam, at least, avoided the embarrassment of having a spacecraft built by students beating its mother ship to the surface. Unfortunately, even though its deployment did eventually occur, it failed to send back any of its planned images after its Wifi-type communications with the IM-1 mother ship communications relay also failed.

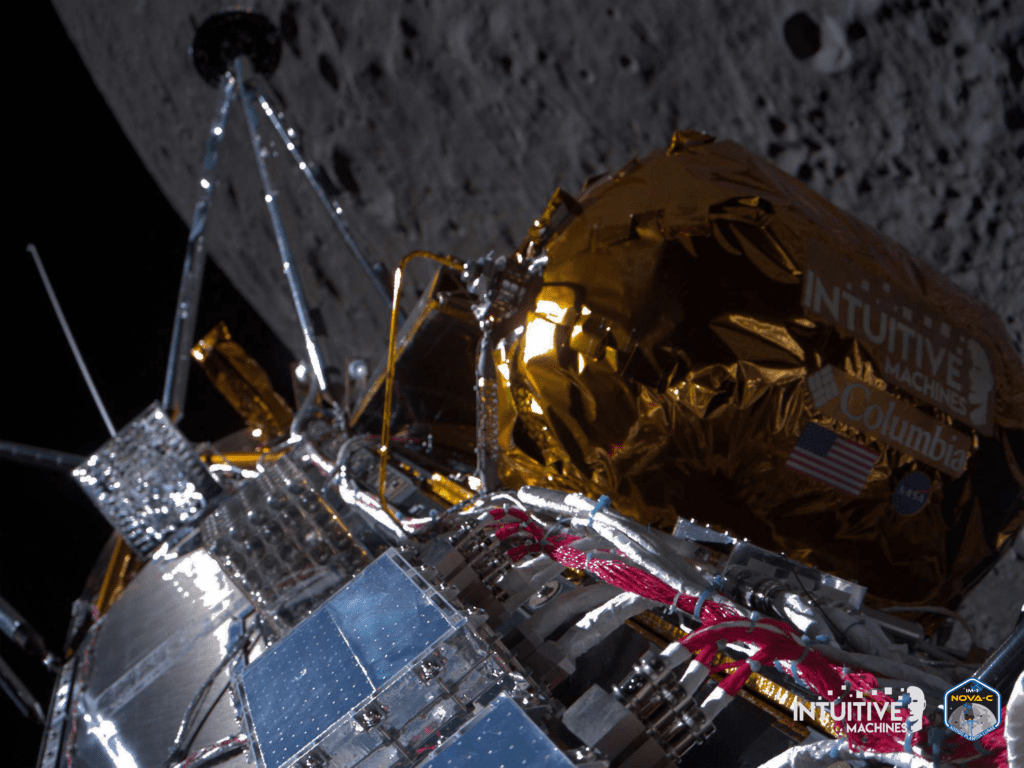

A view of Odysseus on its way to the Moon. Courtesy: Intuitive Machines.

The landing of IM-1 proceeded with a deceleration burn of 11 minutes, followed by a gimballed pitch over manoeuvre about 1 km above the lunar surface in order to begin a vertical descent. However, just before landing, communications with IM-1 were cut for several minutes and controllers feared the worst as they awaited confirmation of the touchdown. The Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station in Cornwall, UK, was eventually able to detect a weak signal from the lander’s high-gain antenna. After some troubleshooting, full data was received and it was finally confirmed that IM-1 had reached its destination.

At least it did not land on its head (ahem, JAXA)

Intuitive Machines, which built the craft, provided an upbeat announcement after its safe landing, noting that it was producing good telemetry, solar charging and that it had been commanded to download science data by its flight controllers. However, the company, which also operates IM-1, later revealed that the lander was on lying at an angle of 30 degrees relative to the horizontal following a ‘crash landing’ on a 12 degree slop in which it had partially tipped over.

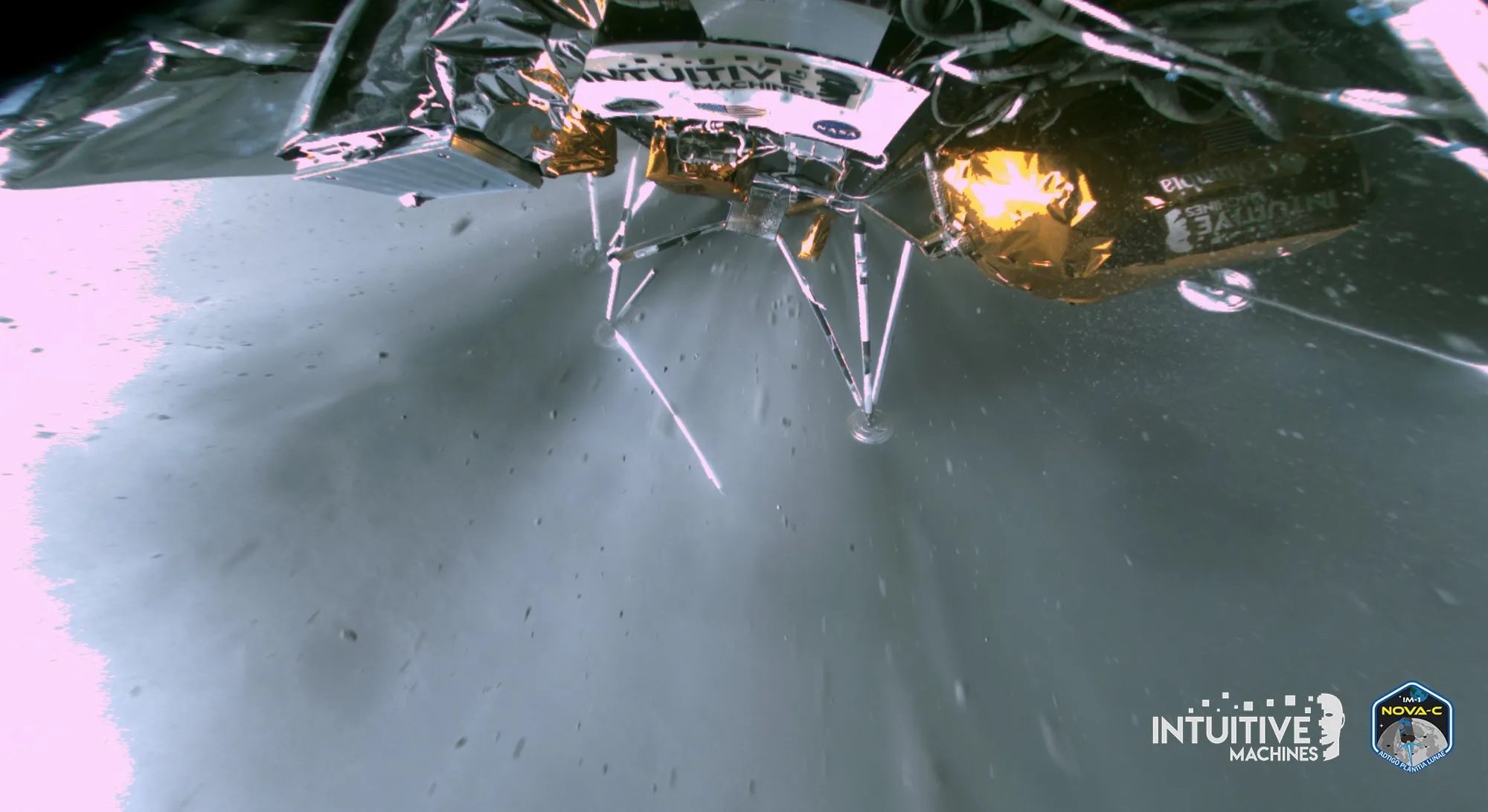

IM-1 Odyssey breaks one of its legs (left) during its rough landing. Courtesy: Intuitive Machines

The landing had taken place with a vertical velocity of 3 m/s – about three times greater than was expected due to the fact that the new lasers only worked until about 15 km and the height estimation system using the accelerometers along with the laws of motion subsequently underestimated the altitude – it thought it was 100 m higher when it landed meaning that its velocity had not been slowed enough by the engine. Worse still, IM-1 had a 1m/s horizontal component as it descended. This caused it to skid across the surface.

It is thought that as this happened, a leg was caught on the surface and snapped, resulting in the spacecraft partially tipping over. Despite this, communications – however weak – were achieved with IM-1. The unexpected position of the lander resulted in a low data rate because the craft’s antennas were not ideally pointed. There was relief that the lander had most of its experiments – including most of the NASA ones carried under the CLPS contract – on the exposed surface, so some had a chance to work still. However, these were not all smooth sailing: the single image secured for an art project experiment was mainly unusable while NASA’s ‘Stereo Cameras for the Lunar Plume-Surface Studies’ experiment failed as its cameras were damaged during the crash landing.

Anatomy of a fall

Image from IM-1 Odyssey as it lies lopsided on the Moon. Courtesy: NASA/Intuitive Machines

Dr Phil Metzger, Director, Center for Microgravity Research & Education at the University of Central Florida, explained the issue on Twitter/X: “A bit of physics to help understand why this happens. When a lander is tipping, inertial forces push it over, while gravity pulls its feet back down flat. On the Moon, gravity is reduced by a factor of 6, but inertial forces are not. Everything is 6 times tippier on the Moon.”

Steve Altemus, CEO of Intuitive Machines notes the tipped over position of the IM-1. Courtesy: NASA TV

Time runs out

IM-1 was expected to be in operation for about seven days on the Moon. In the first update after it landed, Intuitive Machines said it might be operable for up to 10 days in a best-case scenario until the lunar night arrived. However, three days later the company revealed that the lander’s battery life might only continue for less than a day, cutting short its time in operation on the Moon. Rather than try and eek out the power, Intuitive Machines opted to use maximum power to get as much experimental data back to Earth. In the end, it operated for seven days on the Moon. On 29 February IM-1 was deliberately powered down in a hibernation action just before the lunar night. There is hope that the lander might be revived afterwards, although it was not designed to survive such low temperatures.

Comment by David Todd: Intuitive Machines (with NASA) is calling the IM-1 Odysseus mission an “unqualified success”. Well, Seradata’s estimate is that due to the hard landing, about 25 percent of the expected experimental data was lost, plus a small life loss. Definitely a success…but a ‘qualified’ one. Tipping over at landing seems to be becoming a habit for lunar landers. The previous lunar landing attempt by a robotic lander, the Japanese Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM), also came a cropper in this way and ended up on its head, although it survived and has got through its first lunar night. It was the risk of tipping and breaking a module leg that led Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong, who piloted his mission’s Lunar Module to its successful first human landing, to later criticise himself for letting the lander ‘skid in’. Thankfully his lander did not break a leg or tip over.

Some commentators are worried that tall landers might be especially prone to this effect – the concern being that the SpaceX Starship-based HLS design, which is set to carry Artemis astronauts, might also suffer this.