The former Space Shuttle launch pad LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center hosted the first crewed launch since the Space Shuttle was retired after its last flight in July 2011. The launch was the first commercially operated one involving NASA astronauts, with SpaceX acting as both launch provider and spacecraft operator for the mission.

After weather delays put back the launch by three days, the launch of the Crew Dragon spacecraft, named Endeavour (as a successor to the previous Space Shuttle orbiter with that name) on its DM-2 test flight, took place at 1922 GMT on 30 May. As planned, the reusable first stage was recovered from the drone barge, Of Course I Still Love You, hundreds of kilometres down range. NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken – both Space Shuttle veterans – were transported on a test flight to the International Space Station (ISS). The initial orbit achieved was 190 x 211 km at an inclination of 51.6 degrees, with the spacecraft using its own propulsion systems to raise itself by about 200 km to reach the ISS.

Update on 1 June 2020: After an automated approach, the Crew Dragon Endeavour Crew successfully docked with the International Docking Adapter 2 (IDA-2) which is itself attached to the Pressurised Mating Adapter 2 (PMA-2) on the ISS at 1416 GMT on 31 May. The crew opened the hatches and transferred into the space station later that afternoon. As is tradition on the ISS, a bell was rung to announce a new spacecraft’s arrival.

This was the first test flight in NASA’s move away from operating space launches to low Earth orbit (LEO). Instead, it is hiring taxi rides from the private sector – namely SpaceX and Boeing. Both have received sponsorship from NASA to help develop their commercial crew technology.

NASA’s aim is to free itself to concentrate on human “exploration” activities: going back to the Moon and onwards to Mars. The plan was initiated by President George W. Bush (along with NASA Administrator Mike Griffin), who viewed the Space Shuttle as too unreliable (actually new systems like Crew Dragon may prove less reliable in the near term) and too operationally expensive to proceed with. The programme was carried on by President Barack Obama and NASA Administrator Charles Bolden.

The commercial crew programme has been beset by delays, causing a nine-year hiatus during which the USA became embarrassingly dependent on Russia to launch its crews – at very high cost – to the ISS. In effect, NASA was already paying for rides via its purchases on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft/launch vehicle combination. Now, it can keep this money inside America – something the US taxpayers will no doubt approve of.

US President Donald Trump, who watched the launch along with NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, emphasised this point. “Past leaders put the US at the mercy of foreign nations to send our astronauts into orbit. Not anymore.” He added: “Today we once again proudly launched American astronauts on American rockets – the best in the world – from right here on American soil.”

If this test flight is as successful as the previous unmanned flight of Crew Dragon, then SpaceX will be paid US$2.6 billion to carry astronauts to the ISS on six flights.

Comment by David Todd: We at Seradata give our congratulations to SpaceX and NASA on getting USA back in the space transportation business. With race riots (triggered by the Minnesota police killing of George Floyd) coinciding with a major US national launch, it had a déjà vu feel of the 1960s (even if this correspondent was just too young to appreciate that era).

And yet it was very different. Technology, especially on the inside of the spacecraft, has moved on. Gone are the “clockmaker’s shop” sets of dials and switches, which astronauts had in front of them in the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo craft. Even the last renditions of the Space Shuttle Orbiter had some of these dials and switches to back up its “glass cockpit” computer screens. Now, however, the cockpit of the Crew Dragon consists almost entirely of touch-screen controls and the crew does not even have a control stick.

We are not sure we approve. True, those old systems did pose a potential fire hazard (e.g. sparking switch contacts) but, overall, they were reliable and repairable in an emergency – witness Buzz Aldrin fixing the Apollo 11 lunar module ascent engine arming system with a pen. Likewise, those old systems did not have all their eggs in one basket, with the risk of losing them all if one went down. The same may not be true if Crew Dragon screens go wrong.

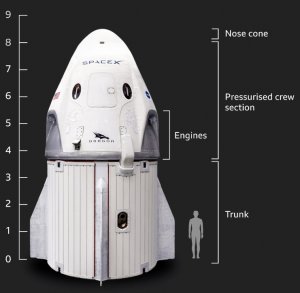

One final thing. While we are glad that this launch and the spacecraft worked, we continue to have serious reservations about the hazard of having powerful wall-mounted engines, such as the SuperDraco type, on the Crew Dragon capsule.