Starship IFT-2’s test flight was a highly anticipated event as it marked the first follow-up to the launch vehicle’s maiden flight failure earlier in the year. There were long delays as SpaceX had to prove that the rocket was safe to fly. This was no easy task after severe gouging took place on the pad with debris blown up for several kilometres during the first launch. There was also a fault with the rocket’s self-destruct system initiation.

Eventually, the fixes and the paperwork were completed and, after a wonky grid fin caused a day’s delay and a late pressurisation query, the launch was finally able to take place on 18 November within a 20-minute window. Lift-off from SpaceX’s Boca Chica base in Texas took place smoothly at 1302 GMT, with all 33 Raptor engines of the ‘Super Heavy’ first stage firing successfully – several failed during the first flight.

Starship IFT-2 lifts off from Boca Chica. Courtesy: SpaceX

The climb appeared to be smooth before the next key part of the flight. In the first flight, separation took place before the upper stage ignited. This time a more efficient ‘hot staging’ technique was used whereby the Starship upper stage would fire its own six Raptor engines, with their fiery exhausts venting sideways through grids between the stages. This happened, as planned, at 2 minutes 45 seconds into the launch.

Starship continued to soar into the darkening blue sky until disaster struck the Super Booster. This was expected to pitch over and initiate a return to launch site burn. The booster stage was never expected to try to land in true reusable style, instead it should have splashed down in the Gulf of Mexico – as intact as possible – so that its systems could be examined. However, the booster stage dramatically exploded into thousands of pieces.

Starship Hot-Staging event on IFT-2. Courtesy: SpaceX

‘It matters not’ is the likely response from SpaceX. After all, the main part of the mission was to test the Starship first stage and this appeared to fly well. It was aiming for an ‘orbit’ with a perigee within the Earth’s atmosphere. In effect, this ‘trans-atmospheric orbit’ would not be able to complete a circuit as the upper stage/spacecraft would re-enter over the Pacific near Hawaii. This almost complete fractional orbital flight could also be considered a suborbital test flight – albeit a high energy one.

The super heavy booster exploded in the air, and it was insane to watch in person

Starship 🤯🚀👽👀🔥 pic.twitter.com/gMr5XfShmY

— Tesla Owners Silicon Valley (@teslaownersSV) November 18, 2023

So, did it reach that part of the test? Sadly no, as communication with the stage was cut shortly before the engines were due to shut down. SpaceX later confirmed that a self-destruct sequence of the flight termination system had been automatically initiated and it had thus exploded. When it did so, it was well into space (as defined by the 100 km Karman line limit) and at 148 km altitude, with Starship only about 1,000 km per hour short of orbital velocity.

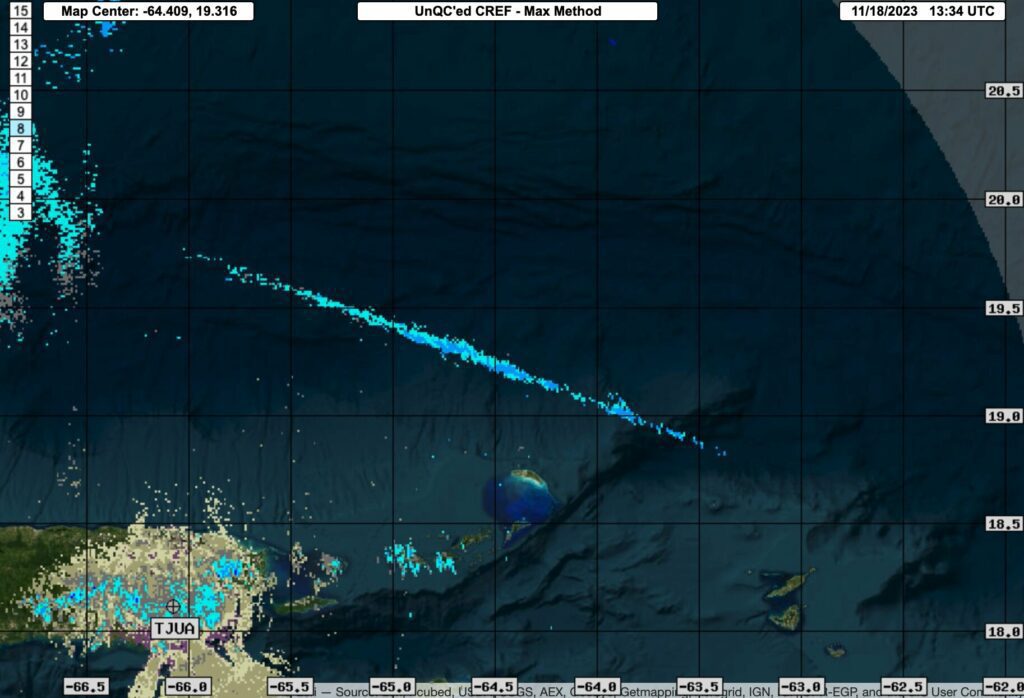

Radar image of re-entering debris from Starship IFT-2. Courtesy; NOAA via Jonathan McDowell/Twitter

While the flight was a failure, experienced space observers were impressed that many of the riskiest elements of the flight had been achieved. Elon Musk, founder and CEO of SpaceX, congratulated his team on the launch. SpaceX will also be happy with how well the launch pad and its new water cooling/noise suppression system survived.

Large nose section piece of Starship upper stage survived self destruction as imaged by an astronomer. Courtesy: Twitter/@astroferg

Nevertheless, questions remain about why the first stage blew up. For example, was it related to the host staging exhaust impinging on the structure? The upper stage failure was more of a mystery and an investigation has begun, which the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) expects to oversee. One concern was that large parts of the structure remained intact after the explosive self-destruction.

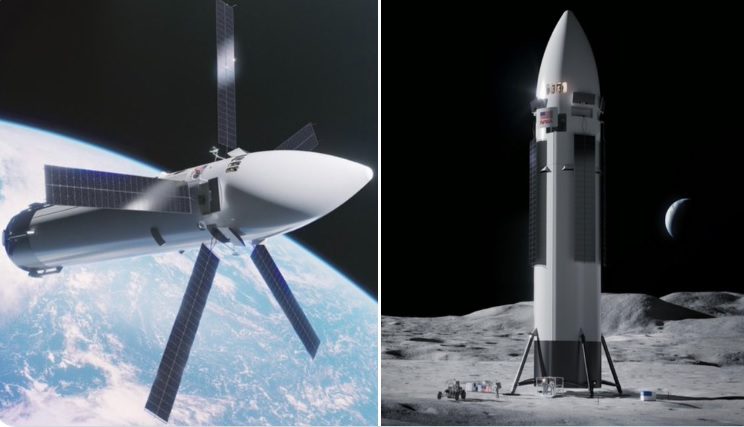

Latest artist impressions of the Starship based HLS lander. Courtesy: SpaceX

Comment by David Todd: NASA will have given a sigh of relief to see at least some progress, since the agency plans to use a derivative of the Starship upper stage for its Human Landing System (HLS). However, the failure provides some evidence that the SLS is still needed as an interim Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle (HLV) for a while longer – even as NASA struggles to keep its per launch cost below US$2.5 billion. That said, many are concerned that a human lunar landing attempt using a Starship derivative – planned for Artemis III (or more likely Artemis IV) – will require over 10 Starship flights to allow cryogenic refuelling of the HLS. We at Seradata have remained sceptical of NASA’s decision to employ untested cryogenic refuelling and storage technologies for the initial Artemis programme lander, preferring a much simpler concept for it and a transfer stage using storable propellants. At the end of the day, only two astronauts are going to use such a lander to reach the lunar surface on initial flights and Starship is not only behind schedule with immature propellant technology, but also hugely oversized.

This story has been added to with new images.