David Todd looks woefully at how Reaction Engines, the promising startup he once invested in, has ended up on the point of bankruptcy.

It was the promise of a reusable rocket that would cut launch costs tenfold that enticed me to become a shareholder in space engineering firm Reaction Engines Limited (REL). That, and the ability to impress people at parties with my insider knowledge of a company planning to build a single-stage launch vehicle called Skylon, powered by a pair of mid-mounted Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engines (SABRE). “That’s right,” I would tell them, “Air-breathing.”

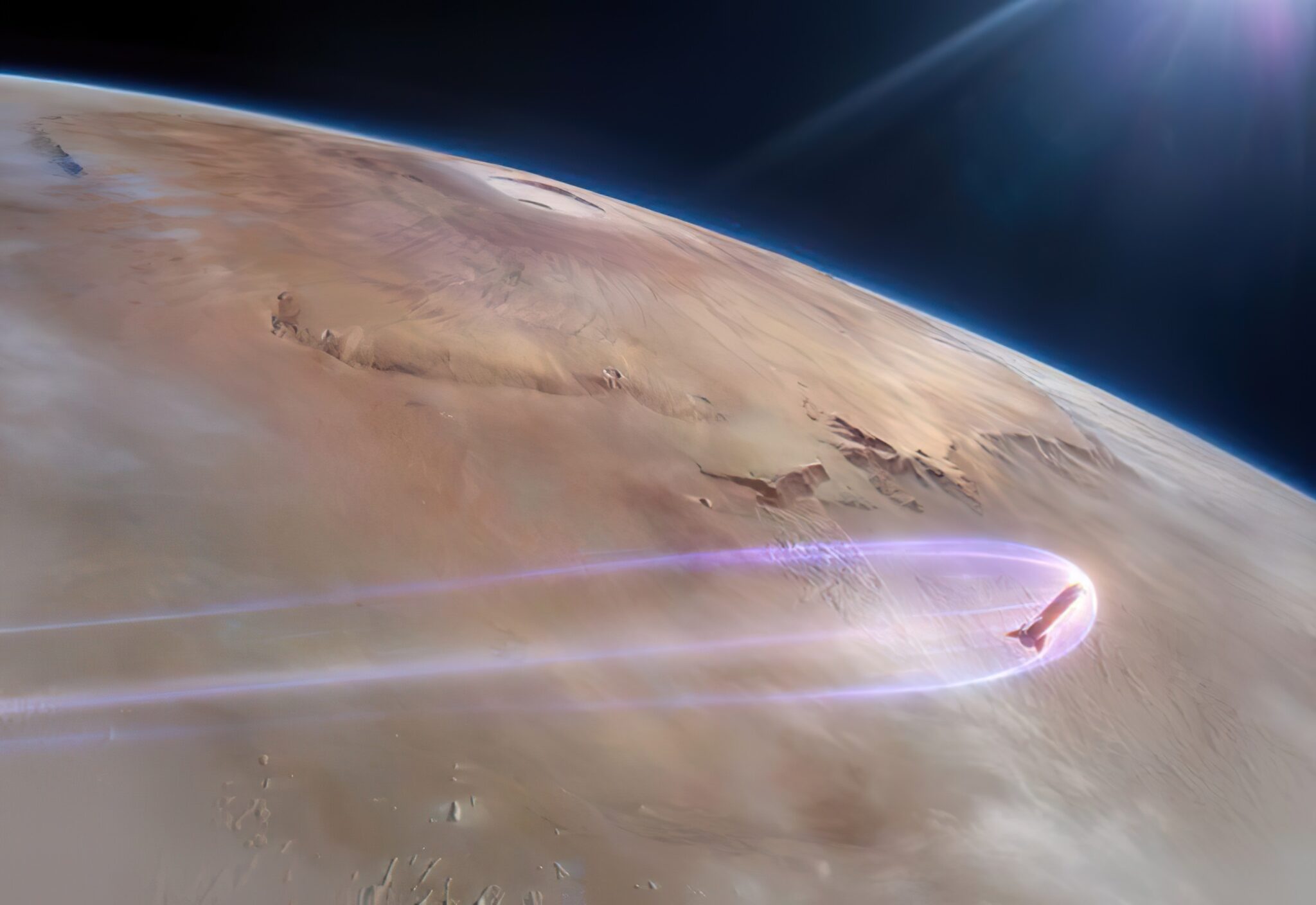

The original Skylon concept was designed to be able to take off and land on conventional runways. Courtesy: Reaction Engines Limited

Conventional rockets carry oxygen to burn fuel (in this case hydrogen). As oxygen is heavy, the vehicles require multiple rocket stages to carry enough payload. However, if air from the atmosphere is cooled and compressed it can be used instead. The less oxygen onboard a rocket, the more payload mass is freed up. It also means that only one stage is needed: a much cheaper venture.

Sadly, after 35 years of trying to develop a single-stage reusable rocket able to carry a significant payload to orbit, the start-up (if it can still be called that) went into administration.

At the start

Rocket engineers Alan Bond and Richard Varvill began working on the concept of an air-breathing engine on a single-stage launch vehicle while designing the HOTOL (Horizontal Take-Off and Landing) spaceplane in the 1980s. However, the British government deemed the idea too advanced to be a worthwhile investment at the time.

In response, Bond and Varvill set up Reaction Engines (REL) in 1989 to prove the heat exchange technology and to power Skylon, an improved version of HOTOL. The pair used initial investment into REL, including a few thousand pounds from your correspondent, to figure out what they needed to make a credible case for their concept. A tour of US aerospace firms, many of which already knew how to build rockets, helped the founders realise that the heat exchanger was the key to unlocking the industry’s imagination.

Promising progress

Bond and Varvill toiled away to nearly perfect the heat exchanger technology that could cool inlet air by more than 1000 degrees Celsius, so that the air could be directly injected into a rocket chamber.

Such technology held, and still holds, the potential to dramatically improve the efficiency of engines used in jets, nuclear engineering and even Formula One racing cars. So, it was no surprise that the company created some buzz when it accomplished successful testing by cooling the inlet air of fighter jet engines. Such was the reception for REL’s progress that George Osborne, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, paid a visit to its UK test facility.

At one point, Skylon was even a viable challenger for the position of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) next major launch vehicle. However, ESA opted to fund the development of the Ariane 6 design. The agency’s official excuse for selecting a rocket that was already out of date was its concern about the technology readiness of Skylon and its air-breathing engines.

Critics believe it was more about protecting aerospace jobs in France and Germany. This was the wrong choice. Instead of challenging SpaceX Falcon 9 and the Starship for reusable launch supremacy, Europe has been left with Ariane 6: an expendable, and prohibitively expensive, rocket that nobody wants to fly on – or at least, not at the prices quoted.

Undeterred, REL continued with its novel research. Bond and Varvill originally wanted to move directly to Skylon using SABRE with government funding – always an unrealistic prospect in this writer’s view. They wanted to run before they could walk.

Reaction Engines’ revised its SABRE engine to a smaller single nozzle design to have more applications. Courtesy: Reaction Engines Limited

REL changed tack in 2015 when Mark Thomas, former Chief Engineer of Rolls-Royce, took over as CEO. REL’s new management decided to build a scaled-down version of the SABRE engine with a view to using it on smaller hypersonic aircraft and missiles. The plan was that once this smaller engine had been built and successfully flown, then a larger SABRE could be used on a full-size horizontal launch vehicle. Subsequently, the company became involved in the UK’s Hypersonic Technologies & Capability Development Framework (HTCDF).

Hypersonic aircraft using SABRE engine. Courtesy: Reaction Engines Limited

Running out of cash and too many staff

Despite the company’s newfound wisdom in taking smaller steps, other mistakes were being made. Management had allowed REL to become bloated. From fewer than 20 people at its inception, the company’s headcount soared to 208 by 2024. Too many were, to put it bluntly, in managerial or administrative functions – not ideal for a research firm with finite resources. REL was, in many ways, oversized for what it was achieving and for its limited revenues. The income and prestige from Formula One were not enough.

Although it attracted equity investments from Rolls-Royce, Boeing and BAE Systems, its last pleas to its investors for another £150 million went unanswered. Perhaps its biggest mistake was not bringing more European aerospace firms into the fold.

End of the climb

It remains a crying shame that this innovative UK company may be lost. REL was achieving good things on the research front. “All the technology on precoolers was pretty much cracked,” said one company insider, before adding “it is a tragedy (for the UK) to lose this.”

The firm reportedly only needed £20 million in cash to survive – albeit with some downsizing – before revenue from four research contracts were due to arrive to save it. As it stands, all but 35 of the staff were laid off after the company went into administration. There are calls for the UK government to front up this money – small beer in budgetary terms – to save this technology for the nation. After all, the British government rescued Rolls-Royce from bankruptcy in the early 1970s when the British jet engine firm was suffering from low cash flow because its RB-211 turbofan family was taking so long to develop.

Keeping the air-breathing rocket technology alive

It is unlikely that REL will survive without this cash. In that case, there are calls for the technology to at least remain in British or European hands. Some fret that if Rolls-Royce gets first dibs, REL’s technology could end up being filed away and forgotten like the HOTOL research. Through its contracts ESA may also have a claim to REL’s intellectual property (IP). In a way the European agency might be a better home. ESA might be more enthused about air-breathing reusability – and make a better choice the next time it must pick a launch vehicle.

That said, I do not claim that I never had doubts. Although I loved the concept of the technology, I worried about how thin and fragile the tubing was even though the tubing was inherently stiff when pressurised. I also wondered about the manufacturing cost of the heat exchangers. Yet REL has reportedly managed to reduce the development costs of its heat exchanger, making it worth saving.

Perhaps imitation is the best form of flattery. A new Canadian company called Space Engine Systems is working on the Hello Series — Space Engine Systems of hypersonic aircraft and launch vehicles. These are modelled on a similar air-breathing concept, only with a slightly different heat exchanger design and a turbo-ramjet cycle rather than a rocket one. Wisely, it is starting small before scaling up. This writer, and failed space investor, wishes them every success…if only to cut Elon Musk down to size.