Every year Seradata Space Intelligence reports on the ‘Great Space Race’ – that is, which nation will be next to set foot on the Moon and which will be first to reach the surface of Mars. David Todd analyses the odds and picks his runners and riders from the main nations competing.

Courtesy: Chris Hart

The method

Seradata’s analysis judges each space programme based on its technological capability, financial resources, national commitment and, most importantly, project progress. To quantify each nation’s chances of success, we use traditional betting odds – a precise way to express probability. Here’s how our odds system works:

When we say a nation has 1-1 odds (called ‘even money’), it means a 50% chance of success. Think of it this way: for every one unit of failure, there’s one unit of success – hence a 50-50 split. The odds format “X-1” shows how many failures are expected for each success. For example, 2-1 odds mean two failures per success, giving a 33% chance while a nation with 4-1 odds would have a 20% chance. For ‘odds-on’ favourites, we use “1-X” odds. For example: 1-2 odds (read as “one-to-two”) means two successes expected per failure, giving a 67% chance. 1-3 odds means three successes per failure, giving a 75% chance.

This year we’ll start with China because, well, (spoiler alert) it’s in the lead.

China (1-2 Moon, 5-1 Mars)

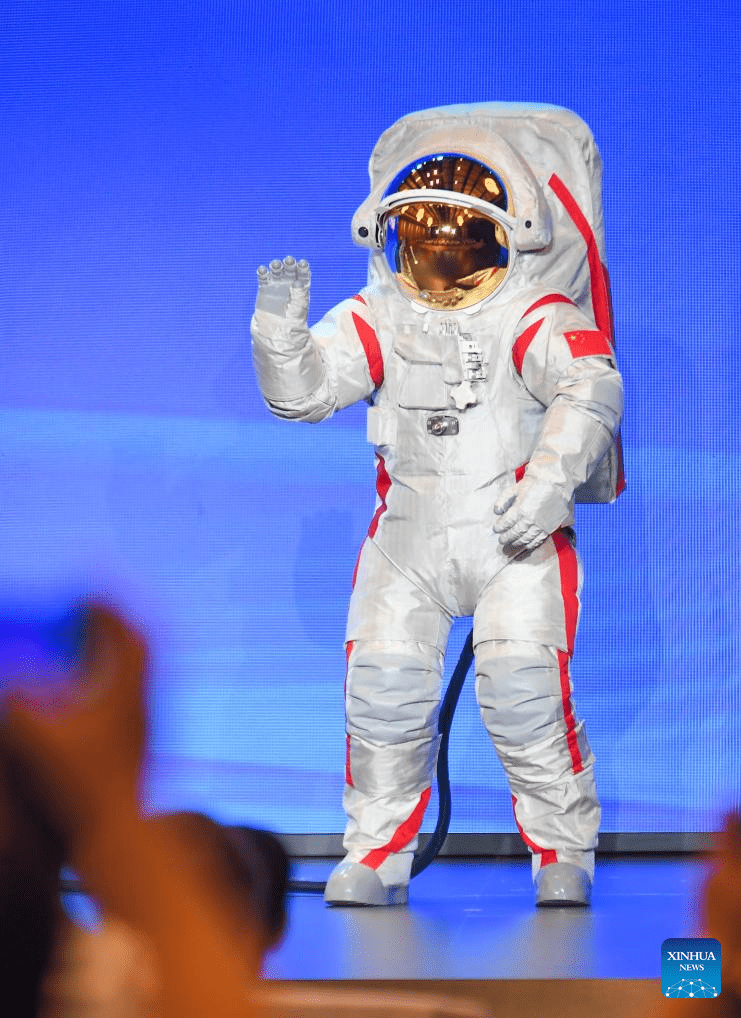

China has emerged as the frontrunner for the next lunar landing. Earlier this year it signalled how close its astronauts (dubbed Taikonauts) are by revealing the spacesuit they will wear to walk on the lunar surface. Its prospects for Mars are not looking as promising.

Chinese lunar space suit design. Courtesy: Xinhua

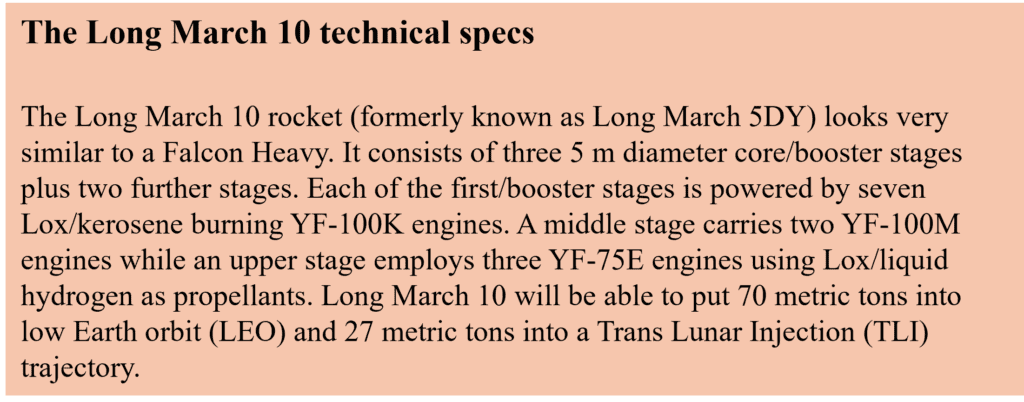

Long March 10: China’s unlikely hero

China originally planned to use Long March 9 (CZ-9), a super heavy lift rocket, for its lunar landing attempt. After changing its concept from a design akin to the SLS to a Superheavy/Starship concept, the nation has since realised that its favoured vehicle will not be ready in time for Taikonauts to reach the Moon by 2030. Rather than wait for the perfect rocket (we are looking at you, NASA), China has decided to repurpose its Long March 5 hardware to build an interim rocket: Long March 10 (CZ-10).

This interim rocket will be used in a two-launch strategy for human moon missions: one to deliver the Lanyue landing craft/propellant stage to lunar orbit and one for the crew transfer spacecraft Mengzhou.

How the Long March 10 is going to take China to the Moon:

An initial single-core version of the Long March 10, called the Long March 10A, will debut in 2026 carrying Chinese crew capsules to LEO. This will be followed by flights of the full three-core Long March 10.

The crew spacecraft and landing craft/propulsion stage, each weighing 26 metric tons, dock in lunar orbit ahead of a Moon landing attempt. There is no Apollo-style ascent module substage of the lunar lander. Instead, after the landing and excursion activities, the landing module lifts itself off in one piece using four 7.5 kN engines. It then redocks with the crew spacecraft which receives the crew to make their journey back to Earth. As part of the missions, two Apollo-style lunar rovers from CAST and SAST have been ordered for development. These will allow astronauts to make 10 km surface excursions.

Diagram showing two part reusable Long March 9 configurations along with one fully reusable version. Courtesy: weibo

Long March 9:

Long March 9, even though it will not get the glory of delivering Taikonauts to the Moon for the first time, is still crucial to China’s long-term ambitions on Earth’s natural satellite. It is with Long March 9 that China plans to eventually build a surface base on the Moon.

So, with its Long March 10 heavy-lift rocket underway and a two-stage preliminary version (Long March 10A) scheduled to fly next year, China is increasingly close to completing a human mission. Seradata’s prediction is that an attempt may be made in 2028, which could beat the US. As such we assess China to be the new odds-on (1-2) favourite from being even money last year.

Model of the Long March 10 as shown in the National Museum of China. Courtesy: Wikipedia

Mars

China has no official plans to land on Mars – yet. Although it won’t admit to being in a ‘race’, it does want to beat the US to the red planet. Its uncrewed sample return mission to the planet is scheduled for 2031, making it likely to beat any US or European attempt where progress has been crippled by rising costs. However, the development of the SpaceX Super Heavy/Starship combination moves China out a point from 4-1 to 5-1 in the race to Mars.

Model of the proposed Chinese human lunar lander and its propulsion stage. Courtesy: Cosmic Penguin

US (5-1 Moon, 1-2 Mars)

Late Starship lunar lander developments push out the US odds for a lunar return from 3-1 to 5-1, but it maintains its leading position in the Mars race. It is still 1-2 odds-on favourite for Mars.

SpaceX Starship-based Human Landing System (HLS) for NASA. Courtesy: NASA

Artemis III

NASA will use its Human Landing System (HLS) with the Orion spacecraft to put humans on the Moon (again) in the Artemis III mission. The design of HLS is based on the upper stage of the SpaceX Starship. Taller than the Statue of Liberty, some worry that the HLS could be prone to toppling over. Landing in the low gravity environment of the Moon is a notoriously difficult feat without this added problem. NASA hopes the use of cryogenic propellants and mid-mounted landing thrusters on the HLS may be able to counter this.

Technical issues aside, is the Artemis III first landing still going to happen on time in late 2026? The answer is now no. The Artemis II mission will take place in mid 2026 with Artemis III pushed out to 2027 according to NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. The reason is that the Artemis I skip trajectory caused extra heat retention which caused dramatic erosion of the heatshield. This was mainly due to the fact that during the skip the permeability of the Avcoat ablative layer was reduced and bubbles built up with a pressure differential causing cracks and spallation (bits dropping off). A fix involves a modification of the Avcoat layer for later missions (the Artemis II heatshield is already attached) but initially to change of re-entry trajectory of Artemis II to reduce this skip “dwell time” to reduce bubble generation and thus improve the structural stability of the char layer of the Avcoat.

However, even with this, actually it is the HLS which has clearly become the choke point for the US endeavour to return humans to the Moon. This is because Artemis III can only go ahead after the HLS successfully undergoes an uncrewed test landing on the Moon, which is likely to take place in late 2026 at the earliest. To make matters worse, this demo mission requires cryogenic refuelling (around ten or more times) which has yet to be tested in orbit. Several refuelling tests are scheduled for 2025.

There has been progress in other areas like NASA’s lunar space suit which manufacturer Axiom recently revealed. Courtesy: Slingshot Aerospace/David Todd

However, should any one of these tests go wrong, then an Artemis human landing attempt would inevitably be delayed well beyond 2027, making 2028 more likely.

In that scenario, NASA may repurpose the Artemis III mission as a lunar orbital mission, leaving Artemis IV to become the landing attempt in, say, 2028. Another HLS lander is being developed by Blue Origin for later Artemis flights. It originally competed for the first spot and is of a more conventional design. However, it also uses cryogenic propellants and is unlikely to be ready by 2026. In other words, the US may have thrown away its lead in the race to return to the Moon, making way for China.

In retrospect, it would have been smarter for NASA to have chosen a much simpler lander using storable propellants (such as those used by the Apollo lunar module) for the early Artemis landing flights. This appears to be the route China has taken.

Mars

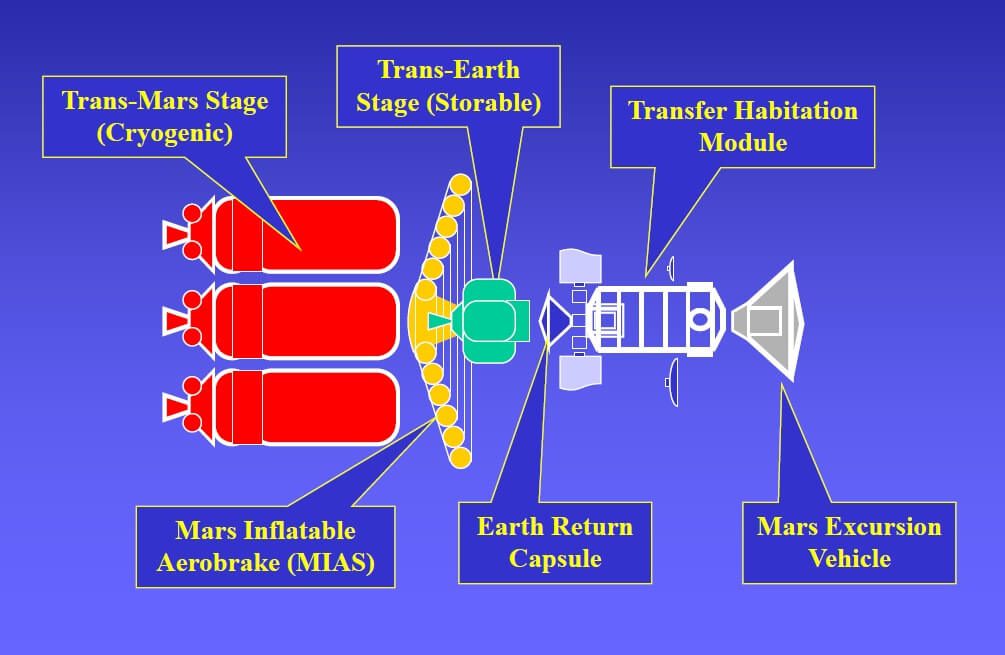

There is better news for the US with respect to the Mars race. With a fully reusable HLV in the form of the Starship/Super Heavy combination about to become operational, the chance of a Mars landing attempt during the late 2030s is very much on the cards. There are two choices of architecture at this point.

Artist’s rendition of Starship entry into Mars atmosphere. Courtesy: SpaceX

Elon Musk’s plan is for initial Mars landing attempts using direct Mars entry and return (he has announced uncrewed Mars landing attempts for 2026). Alternatively, Musk could go with a more conventional NASA exploration architecture using storable propellants for Mars return, albeit using the cryogenic Starship as a key initial propulsion element.

Update on 18 November: There are rumours that a major revolution in the US Space programme is imminent once Trump takes over the US Presidency in January. Some have suggested that SLS will be cancelled completely in favour of an Falcon Heavy modified to take the SLS ICPS upper stage. More likely is that SLS will be retired once existing RS-25 engine supply runs out, allowing it to fly the early Artemis missions. That means that all later SLS versions (e.g. Block 1B and Block 2) using the planned Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) will go and that the development of this will be cancelled. Alternatively, the EUS could be put onto a Super Heavy first stage.

The Blue Origin-led National Team’s concept for a three-stage lunar lander/ascent/transfer craft. Courtesy: Blue Origin

Some have even suggested that Artemis maybe completely scrapped. This will probably not happen, at least not until the early landings are done. More likely is that the lunar orbiting station, the Gateway, will be postponed or even cancelled in favour of a direct attempt at a human Mars landing. Officially Vice President elect J D Vance is in charge of the space programme. However, in effect, Trump supporter Elon Musk is expected to be in the driving seat. (Update on 5 December 2024: Senator Nelson is likely to be replaced by Trump nominee Jared Isaacman early next year)

Elements needed for basic human landing mission to Mars. Courtesy: Bob Parkinson/British Interplanetary Society

Russia (50-1 for both Moon and Mars)

Russia’s cash bleed on the Ukraine war means its Lunar and Mars race odds have moved out to 50-1 (from 33-1 and 20-1 respectively).

The Soviet Union lost out to the US in the original human Moon race in the ’60s. The chip on Russia’s shoulders could have provided the motivation to outpace its old adversary, but the country shows no signs of recovering its position, despite its ambitions.

Russia has a heavy-lift launch vehicle in development. The Yenisei/Don is a 140 metric ton payload-class rocket. It consists of:

- six booster ‘first’ stages, each powered by two Lox/kerosene RD-171MV engines;

- a central single RD-181MV core acting as a second stage;

- a third stage employing a single RD-180 engine, again using Lox/kerosene as propellants; and

- a fourth stage with a single Lox/kerosene RD-11D58M engine.

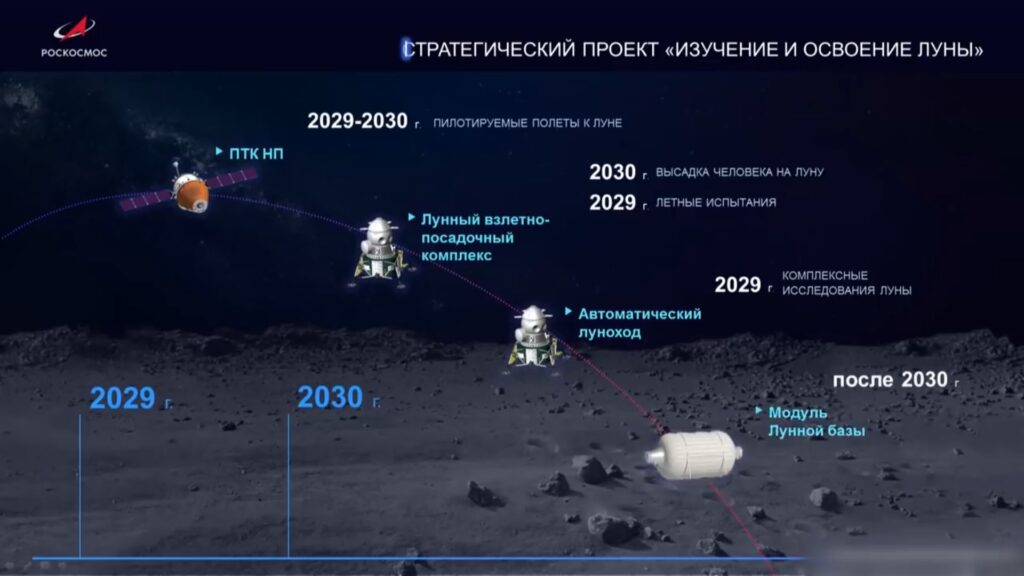

Russia’s schedule to land its cosmonauts on the Moon. Courtesy: Roscosmos

Unfortunately for Russia, few are convinced that the Yenisei/Don will be able to stick to its schedule to make its first flight from Vostochny in 2028.

A handful of images of the Federatsiya, Russia’s planned successor to the Soyuz human-carrying spacecraft, have been released, but there is no word on the programme’s progress. Similarly, there is no news of any lunar landing craft even through its development has officially started. Instead, Roscosmos suffered some embarrassment earlier this year when its Luna 25 lunar lander was lost during a manoeuvre before it could make a landing attempt. The main problem facing Russia is a lack of funding due to the war in Ukraine and the fact that much of its space expertise has expired (or retired).

As such, Seradata cannot see Russia being in a position to launch a human lunar mission before 2040. We have moved its odds outwards accordingly. So, Russia’s lunar return odds are lengthened again from last year’s estimate of 33-1 to 50-1. Mars race odds are similarly lengthened from 20-1 to 50-1.

India (50-1 Moon, 200-1 Mars)

India’s first human flight is delayed but it commits to the Moon: Odds fall to 50-1 (from 80-1) but stay at 200-1 for Mars

India showed off its plans for a human lunar mission at the IAC in Milan. Courtesy: Slingshot Aerospace/Farah Ghouri

India’s first attempt at human spaceflight is expected in 2026, two years later than originally envisaged. Three test launches will take place before that (including one with a dummy Gaganyaan (Indian astronaut) aboard to ensure that everything works. Although the agency has formalised its intention to land its astronauts on the Moon, it does not seem to be in a rush. ISRO wants to achieve the feat before 2040. This ample timeline means that it can effectively be ruled out as a runner in the lunar return race.

Still, the nation should not be underestimated. It proved its lunar prowess with the Chandrayaan-3 mission in August, which saw a lander and rover touch down on the far side of the Moon. Moreover, the country has plenty of other space ambitions to accomplish before 2040. Chandrayaan-4, a lunar sample return mission, is already in the works. India also intends to launch its own multi-module space station, named Bharatiya Antariksha Station (Indian Space Station), into LEO in 2035.

Thus, for the purpose of odds, we rate India at 50-1 for the first human return lunar landing (from 80-1). For a human mission to Mars, India stays at 200-1. That said, the nation has already demonstrated that its spacecraft can reach Mars with its Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), or Mangalyaan.

The other runners: 1000-1 bar for both Moon and Mars

Although Japan and Europe are content to take a back-seat ride with NASA to the Moon, some surprising contenders have cropped up from other corners of the world. While it is an unrealistic scenario, Iran has expressed its desire to attempt a human lunar landing. Meanwhile, South Korea’s space agency, Korea Aerospace Administration (KASA), will attempt a new uncrewed lunar landing, probably in 2032. Whether it expands its ambitions to include astronauts remains to be seen.

Smart decisions put China ahead for the Moon…but the US still holds lead for Mars

The Moon offers significant commercial and scientific opportunities, ranging from astronomy and space tourism to raw materials via mining. So, it is near certain that humans will walk again on its surface within the next 15 years – and probably before the end of the decade. At one point it looked as though the US would run away with the prize. But like the Aesop fable, the slow but sensible Chinese ‘tortoise’ is likely to beat the complacent US ‘hare’. Importantly, China has done this by using technologically ready, rather than advanced, space hardware for interim lunar excursion missions. It plans bigger things later on – often by allegedly copying the ideas of others – but is determined to walk before it can run.

Some architecture decisions made by NASA were driven, unduly some might say, by politics (eg SLS), funding limits and cost pressures. The choice of Starship as the HLS was controversial at the time because of the increasing dominance of SpaceX and some technical concerns. The decision was defended by Kathy Leuders, then head of NASA’s human spaceflight programme, and her team who argued that it was the best option based on cost, schedule, payload capacity and technical capabilities. Leuders left NASA in April 2023 to join SpaceX as Starbase general manager a few months later. HLS may have been the right choice for long-term lunar operations but, in the short-term, remains questionable.

Our estimate is that the ‘China Manned Space Flight Office’ (which ironically plans to send both men and women to the Moon) will be in a position to attempt a human lunar landing by 2028. We think it unlikely that the US will be able to make its bid before then. This means that if China is successful, it will be first nation to return humans to the Moon and effectively make it the leader in human space exploration. With respect to Mars, we can expect a human Mars landing towards the end of the 2030s. That will still probably be a US-led mission – a US fightback if you like.

Farah Ghouri contributed to this story. This story was updated on 5 December 2024 due to the NASA press conference discussing the Artemis I Orion heatshield issue and its effect on the overall schedule.