Every August Seradata does its usual analysis of the “runners and riders” in “The Great Space Race” between the major space nations. Here we judge each space programme on the basis of technological ability, financial and other resources, national will and, most importantly, project progress. In conclusion we assess each nation’s chances in the way that a notional bookmaker would: in the form of odds.

This year there are actually two races we will make judgment on: the race to return humans to the Moon and to place humans on the planet Mars for the first time.

The runners chop and change every year with two major players, the USA and China, being at the forefront of the betting in both markets. Other runners include the once great Russia – then the Soviet Union – which is trying to make amends for losing the race to the Moon 50 years ago – a race won by the USA’s Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Mike Collins on their Apollo 11 mission. Up and coming is India, whose human space programme might not be as morally justifiable as its unmanned space programme but nevertheless has become a national flag waver.

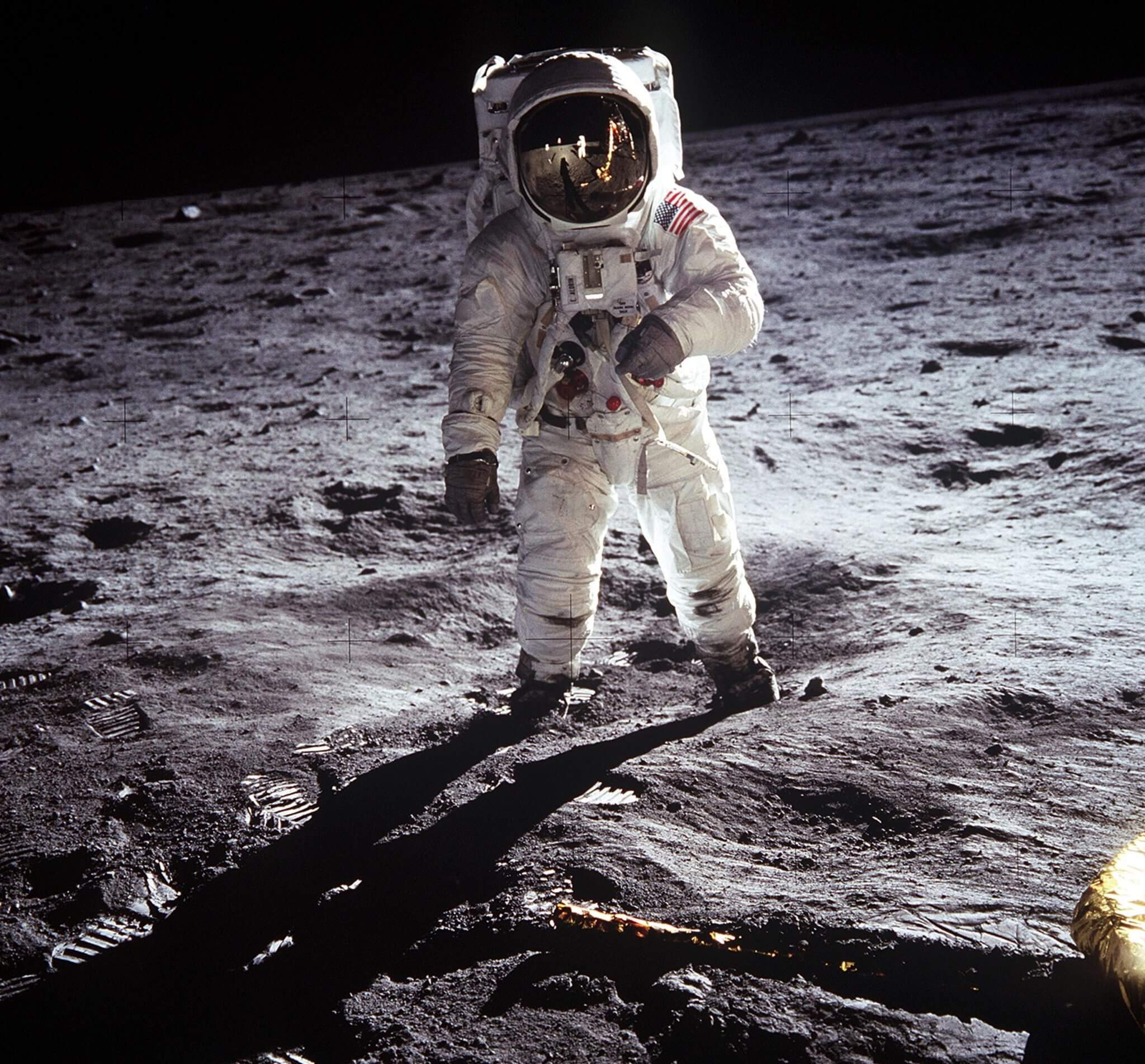

Buzz Aldrin is photographed on the Moon by Neil Armstrong (seen in Aldrin’s helmet visor) during Apollo 11’s lunar walk. Courtesy: NASA

USA: Lunar return odds: evens; Mars race odds: 1-2 (2 to 1 on)

While at one stage it was in danger of becoming bogged down by an international lunar space station concept called Gateway, the Trump Administration, in the guise of Vice President Mike Pence, has moved swiftly to demand that NASA make a human lunar landing on or before 2024. In doing so, he has restored NASA to its favourite status of being first back to the Moon.

Possibly following his master’s bidding, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine demoted Bill Gerstenmaier and his team from exploration leadership and rewrote the plan for the Gateway lunar space station as the newly named Project Artemis. From its original rather grandiose multi-module facility, with a refueling capability for any needy lunar landers etc, this has now been reduced to an initial basic orbiting vessel/habitation module concept. The habitation module is now dubbed the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) has been ordered from Northrop Grumman. To this will be attached a propulsion module called the Power and Propulsion Element. This basic Gateway will be added to, with contributions from NASA’s other space partners e.g. a robot arm from Canada.

There is still resistance to this plan as not being fast enough. Some wonder why you need a staging post at all – at least for the initial landings – and argue that a more direct mission should take place. Unfortunately, the SLS Block 1 is just not powerful enough to mount such a mission with a single rocket. There is an alternative, however. Two such launch vehicles could be used: either two SLS Block 1 launches, or an SLS Block 1 and a Falcon Heavy equipped with an ICPS stage: one for the human carrying Orion capsule and one to carry a lunar lander.

By the way, NASA has at last realised that it needs a lander/ascent vehicle to carry humans (yes, female astronauts will also be on board) to the lunar surface and is funding commercial firms – with Blue Origin and Lockheed Martin as favourites – to come up with designs. One will be for an initial quick-to-build vehicle, which will later be added to by larger, and probably partially reusable one. While commercial firms will make it, NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville remains in overall charge of the project. Its record is patchy. After good initial progress its SLS rocket is now very late.

While the main lunar thrust is this plan, NASA still has its eye on reaching Mars. To that end, it has decided to support financially some of the work on Elon Musk’s Starship design and especially his in-orbit refueling plans. Not only does he plan to land on the Moon with it – in effect it, becomes a back-up plan to the SLS-based lunar effort – he also intends eventually to mount a mission to Mars. And even if that fails, Blue Origin is thought to be working on its own super heavy lift rocket called New Armstrong. It has already announced its Blue Moon lander, although it still lacks an ascent stage.

China: Lunar return odds: 6-4; Mars race odds: 3-1

China has become a superpower in the world of space and now commands the largest number of launches compared with other nations (USA is number two). And it has made significant progress in its lunar exploration programme including using lunar communications relay satellites to allow communications from behind the Moon – a capability not available to Neil Armstrong and his crew half a century ago. It has used this to mount its first mission to land on the lunar far side – Chang’e 4 in January.

The next mission Chang’e 5, will attempt to return samples to Earth, thereby matching the achievement of Soviet Russia in the early 1970s. It plans to continue in this vein with a series of experimental spacecraft landers – some of which are devoted to construction techniques the use material from the lunar regolith – to map the topography and take samples near suspected water ice deposits near the lunar south pole. These missions are with a view to creating a human base on the surface of the Moon.

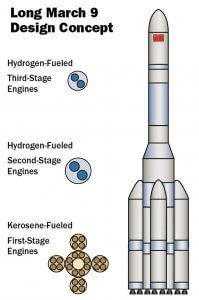

Further missions are concentrating on manufacturing techniques for a Chinese manned lunar base. Before that, China plans to land its Taikonauts onto the Moon. It is already planning a super heavy-lift launch vehicle (HLV). With its 140 metric ton payload to low Earth orbit (LEO) and a 50 metric ton payload to TLI (trans lunar injection), the expendable LOx/kerosene booster/LOx-Hydrogen upper stage Long March 9 is likely to become the largest rocket in the world, with a payload capability nearly twice as much as the current version of SLS. But that will not be ready until 2030.

China could conceivably launch a lunar landing mission before that. Aviation Week and Space Technology reports that China may be working on a smaller HLV carrying 25 metric tons to TLI, leading to speculation that such a rocket might be able to achieve an Apollo class landing before the 2020s are out.

In conclusion, while the Chinese tortoise might yet beat the US hare, even if China does not get its Taikonauts to the lunar surface until after the Americans, it has solid plans to stay.

Whether China then plans to move towards Mars remains to be seen. It must be tempting to beat the USA in that race, if only to demonstrate technical, political and cultural superiority. With the Long March 9 and the ability to assemble modules for a mission starting in LEO, such a mission is entirely conceivable.

So while China has now lost its favourite status in the Moon return race, its odds having moved out from evens to 2-1, this is more in response to the USA speeding up its efforts than to any change to China’s plan. It remains second favourite for Mars.

Russia: Lunar return odds: 10-1; Mars race odds: 8-1

The glory days of Russia’s space programme are very much over. While it still operates the venerable Soviet-era Soyuz rocket and the Soyuz capsule design – in upgraded forms, it has struggled to come up with anything new. It is true that its new Angara rocket has flown – but it is not in full production as it waits for the delayed completion of the Vostochny launch site. The planned rework of its veteran and uncompetitive Proton rocket soldiers to enable it to still compete, has been cancelled for cost-cutting reasons. The human-carrying spaceship replacement for the Soyuz capsule element – Federatsiya – is being developed, but only slowly and this will not fly until late 2022.

Despite all this difficulty, there is a plan to build a modern heavy lift rocket, given that Russia’s original N-1 and subsequent Energia HLVs are now just historical footnotes. The problem is that Russia’s equivalent of SLS – the 100 metric-ton-to-LEO capable Yenisei design – is still just a paper project that has yet to receive formally approved government funding.

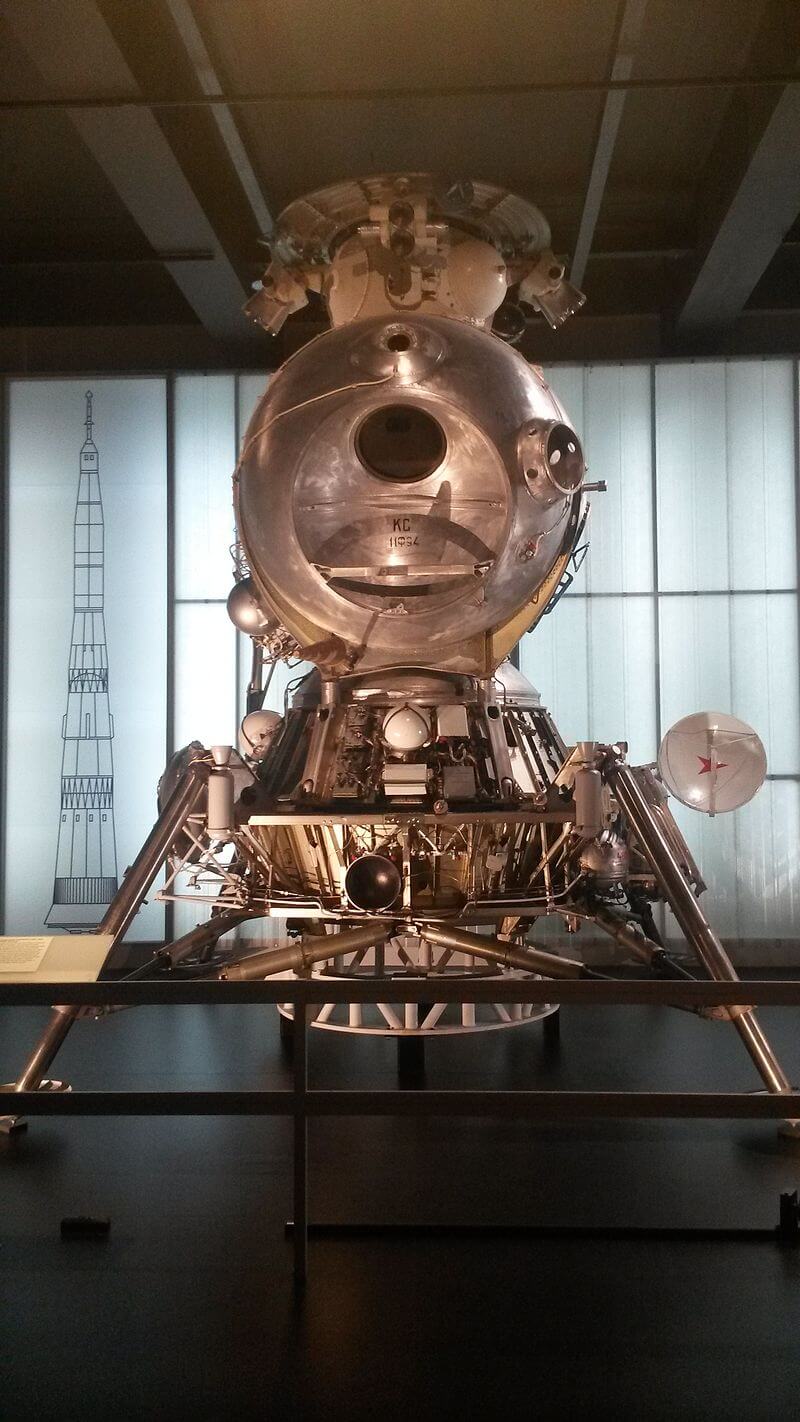

The Russian LK-3 lunar lander (with a drawing of the N-1 rocket behind it) was only designed to carry one cosmonaut. Courtesy: Wikipedia

Russia also needs other parts of the jigsaw if it wants to return to the Moon anytime soon. Like NASA, it lacks a human carrying lunar landing craft – its original LK-3 one-man lunar lander is now just a museum piece. Of course, that lander is a sad reminder of what might have been. It never achieved its design aim due to the N-1 launch vehicle’s failure to get it anywhere near the Moon.

As such, financial reality (it simply cannot find the US$20 billion or so required to build the Yenisei launcher) means that Russia can only be regarded as an outsider for now. So it was not really a surprise that Russia quietly made entreaties to China to work jointly on its long-range human exploration programme.

And yet there are a few signs that Russian pride will not let it give up completely. It still fancies itself as a genuine space race competitor, and its experiments with nuclear rocket engines, ostensibly for missile use (the 8 August 2019 nuclear rocket explosion at Nyonoksa being one example) – hint at a technological attempt to reach Mars in quick time for a human mission. As such, while a lunar mission is unlikely to be ready until after the USA or China gets there, Russia remains a dark horse with respect to the race to Mars.

India: Lunar return odds: 80-1; Mars race odds: 500-1

Just like other nations, national pride, and the hunt for international kudos have led India into the world of human spaceflight. India’s Modi-led government is fully committed to putting human “gaganauts” into orbit on board a spaceship called the Gaganyaan which will be launched by a GSLV Mk III in 2022.

Nevertheless, while it does count unmanned lunar and Mars spacecraft among its achievements, it still lacks most of the jigsaw pieces needed to mount a human-carrying mission. These missing pieces include having a heavy lift rocket and a suitable lunar lander. While it is about to make a lunar landing with its Chandrayann 2 Vikram lander, which presumably could be scaled up for human use, it still needs a very large rocket.

A recent construction of the 1949 BIS design for a lunar space suit is now on show at the UK National Space Centre in Leicester. Courtesy: UK National Space Centre

Thus, India remains very much, the outsider in the lunar and Mars races. But at least it is in them. And perhaps this is a less aggressive and dangerous way for India to promote itself and gain international kudos.

The other contenders: 1000-1 for both races

As for the others, the status has not changed. Unless the European Union (EU) wants to flex its financial muscles, Europe, via its space agency ESA, and Japan, via its agency JAXA, are content to be subordinate to NASA’s efforts – even if their plans to be involved in a large Lunar Gateway space station will probably not happen for some time given that its initial configuration has been scaled down.

Still, ESA, and especially its director general Jan Woerner will continue to press for the construction of a lunar village/base ahead of any quick there-and-back mission to Mars. And as he views China’s plans for a lunar base, US President Donald Trump just might play ball.

Of the other nations, neither Iran nor North Korea has a serious chance of putting humans into orbit in the near future. One rank outsider, the UK, while it is not even properly back in the launch business yet, still has some talented dreamers especially within the British Interplanetary Society (BIS). It was, of course, their lander and space suit designs thought up between the 1930s and 1950s – that so influenced NASA’s later Apollo lunar landing programme.

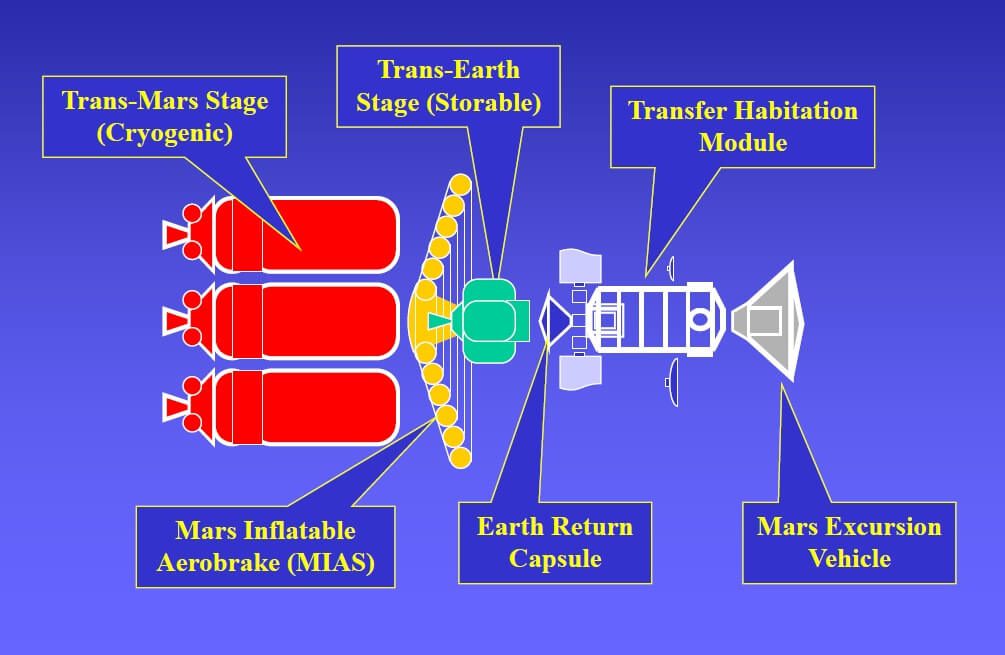

Bob Parkinson’s plan: elements needed for basic human landing mission to Mars. Courtesy: Bob Parkinson

In the same vein, nations wanting to land their astronauts on the surface of Planet Mars might be wise to examine Dr Bob Parkinson’s excellent mission plan for a simplified human Mars landing mission, which he presented at the BIS last year.

While this writer is an admirer of Elon Musk’s plan to reach Mars – if not his Martian colony ideas – Bob Parkinson’s cheap-to-action plan (well, at least relative to others) to put humans on Mars remains the best that this correspondent has seen to date.