Every year Seradata publishes its analysis of how well different nations are doing in the “great space race”. In this, we limit our analysis to manned spaceflight and to its two main exploratory targets: a return to the Moon and setting foot on Mars. On the basis of technological ability, financial and other resources, national will and, most importantly, project progress, we publish our opinion on each nation’s chances in the same way that a notional bookmaker would: in the form of odds.

Two races: One to Mars and one to the Moon

While China and Russia would one day like to go to Mars with their respective Taikonauts and Cosmonauts, neither has viable plans to go any time soon. China has a slow, steady long-term exploration strategy that firmly puts the Moon ahead of its Mars aspirations, and before that its major space station in low Earth orbit (LEO). So while it has been confirmed that the Chinese are working on early plans for manned lunar exploration, there will be no landing on the Moon before 2035.

Meanwhile, Russia could theoretically surprise the world with a cut-down mission to the Moon or even to Mars, perhaps using a reused space station as an interplanetary transfer craft, with a landing craft and ascent vehicle devised for the mission. But where would the money come from?

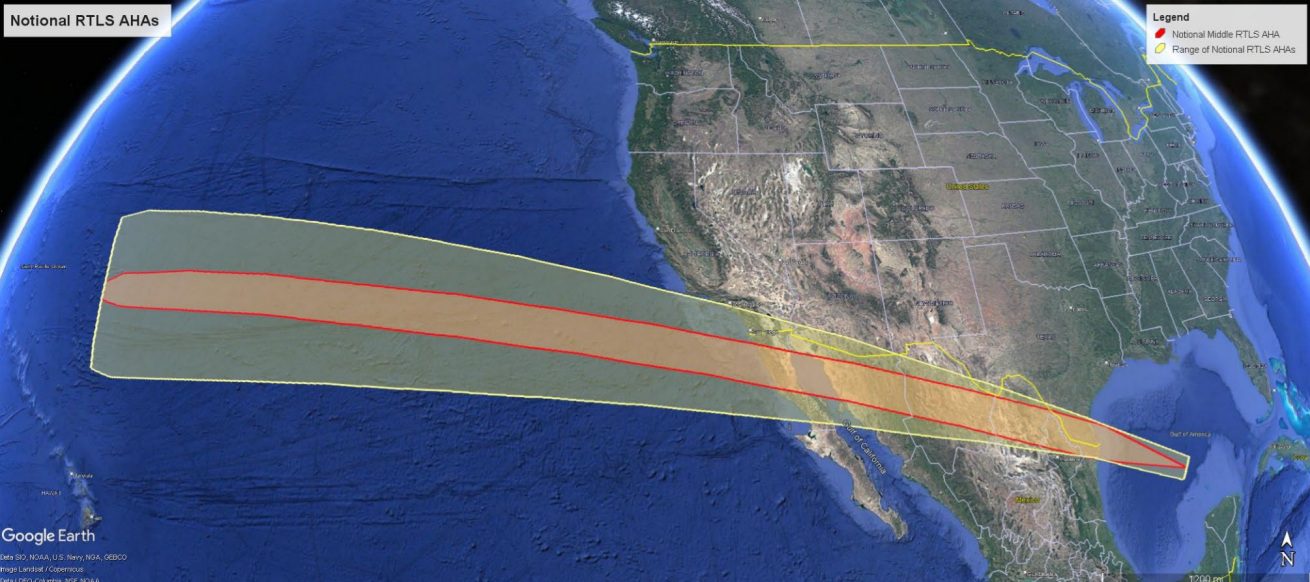

So that leaves the USA. The problem to some extent is money again. The USA only had enough to build certain pieces of its “exploration jigsaw” at a time. The first piece was a heavy-lift launch vehicle. While its SLS launch vehicle is now certain to fly, it remains undersized for Mars exploration even in its later more powerful Block IB and Block II versions – the latter with a payload to LEO of over 150 metric tons. However, for lunar exploration, it can be made to work – albeit in two launch architectures, or one using a cis-lunar space station base.

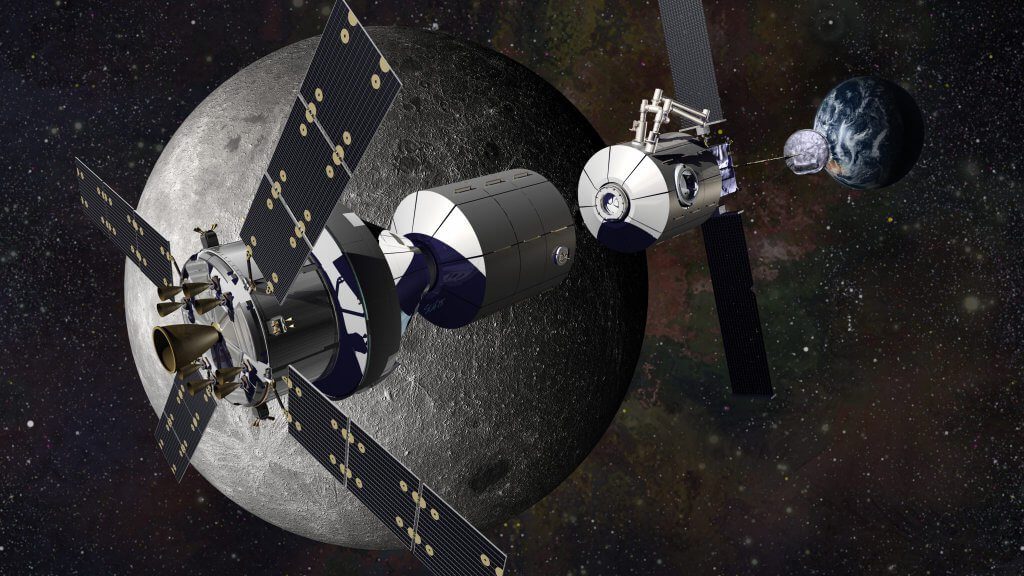

The Orion spacecraft capable of carrying humans is also nearing completion. This would allow missions to the cis-lunar environment to take place – if not lunar landings, which would require a specialist landing craft to be carried on its own SLS launch.

Lockheed Martin design for a cis-lunar habitat which could become the basis for a long range spacecraft. Courtesy: Lockheed Martin

Worse news, however, is that the official government programme run by NASA has been vague on exactly what the mission architecture would look like. The current plan, of which both Boeing and Lockheed Martin have very similar vision, is for the project to start with an initial space station to test out mission elements in a retrograde lunar orbit.

The original plan to use this as part of research into an asteroid brought back into a cis-lunar location has been shelved after the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM) part was cancelled. In truth, the ARM mission had little support apart from within NASA.

As such, with the demise of the ARM, it is thought more likely that any planned Moon orbiting station might be deployed as a technology test craft. It could also be used to mount manned missions to the lunar surface, assuming that a reusable landing craft can be developed. Nevertheless, while lunar exploration could start by the 2020s, Mars exploration remains a distant 2030s prospect.

However, there is something else, or rather someone else, in the race. Elon Musk and his SpaceX firm are major players wanting to land humankind on Mars, even if there have been a few setbacks to their plans on the way.

Musk announced his Mars colonisation architecture at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Guadalajara, Mexico, last year. This included plans for a reusable super-heavy-lift launch vehicle with an LEO payload up to six times the size of the SLS (or three times the size in reusable form).

Red Dragon was to have used its Superdraco thrusters to make a propulsive landing on Mars. Courtesy: SpaceX

In fact, when it comes to Mars it is less of an “international space race” but more of an “intra-national” space race. For while NASA seems in no hurry to get there, Musk and his SpaceX team are also working on an unmanned Mars landing trip in the form of Red Dragon, which is to launch (with NASA’s Deep Space Network supporting it) in 2020.

Nevertheless, his team has had some setbacks – both political and technical. President Trump originally declared that he wanted a Mars landing to happen in his notional “second term”, the inference being that he would have to go with SpaceX as it was the only outfit planning a trip in the 2020s. However, Musk’s relations with the Trump administration have cooled since he withdrew (after the US withdrawal from the Paris Accord on Climate Change reduction).from the now disbanded President’s business council.

Meanwhile, the SpaceX architecture, which has “super draco” thrusters to manage a propulsive landing on Mars, has found difficulty in employing them safely on the Dragon spacecraft for this purpose. Exactly how this affects the design of the so-called Mars Colonial Transport remains to be seen.

One thing more. While Musk previously dismissed the Moon as a human destination, he has now come around, saying that a manned lunar surface base would be a good idea. SpaceX is currently in the process of designing a tourist-carrying “round the Moon” mission using his current space systems.

Of the other nations, Japan’s JAXA will be content to follow what NASA decides to do, as will the UK, which does not have enough money to mount a project of this size independently. The European Space Agency (ESA) is in a similar position, albeit that it remains much more in favour of a lunar surface base, or “lunar village”, than Mars exploration. It would probably not want to be left out of such a project led by NASA, however.

ESA could theoretically develop a Mars exploration infrastructure, using an ESA financed Skylon reusable space plane as the initial transport to LEO. Reaction Engines, the firm developing Skylon, has planned a Project Troy mission design for Mars exploration, but again this would not happen until at least the 2030s.

While India persists with its manned space programme, it is still years away from launching a “gaganaut” to LEO, let alone to the Moon or Mars. And so it remains an extreme outsider. Despite their claims, Iran and North Korea are nowhere near such a programme – except possibly a suborbital one.

Finally, poor little Isle of Man, which for a time became famous as a contender via the Excalibur project, is now a non-runner since the venture’s demise.

So what are the odds?

Since the end of the ARM mission, USA has retaken the lead from China as the out-and-out favourite for being next to land humans on the Moon. China remains a strong second favourite given that it has perfected unmanned landings on the lunar surface.

The USA remains the clear leader to be first to land humans on Mars – although exactly when, and exactly who that will be, remains to be seen. It is a strong possibility that NASA and SpaceX will join up their efforts.

Of the others, only India has a realistic manned space programme at the time of writing, and even that is not certain. So lunar and Mars landings remain a distant prospect even if it did laudably manage to get an unmanned probe to the red planet.

Moon race odds (to be next to return humans to surface of Moon):

USA (Moon Odds): Evens (1 to 1) – probably a NASA mission.

China (Moon Odds): 3-1

Russia (Moon Odds): 10-1

India (Moon Odds): 50-1

Others (Moon Odds): 1000-1

Mars race odds (to be first humans on surface of Mars):

USA (Mars Odds): 1 to 10 (10-to-one on) – probably a joint NASA/SpaceX mission.

China (Mars Odds): 10-1

Russia (Mars Odds): 33-1

India (Mars Odds): 100-1

Others (Mars Odds): 2000-1