Every August, Seradata does an analysis of which nation is leading the “human” space race – or rather races – to return humans to the Moon and put them on the surface of Mars. This year progress has become clearer and the USA is very much the leading contender in both races. But like Aesop’s fable, “The tortoise and the hare”, China just keeps chugging along at its own pace as it watches the USA lurch forward, only to stop in its tracks. As usual, we allocate the contenders relative chances in bookmaker-style odds.

USA: Odds for human lunar return: 1-2 (2-1 On) – 67%. Odds for first human Mars landing: 1-3 (3-1 On) – 80%.

The USA has committed to reaching Mars and returning to the Moon. Despite funding issues, it is slowly putting the pieces of the jigsaw together. It is spoilt for heavy launch vehicles – or soon will be. Not only will it soon have the much delayed and way too expensive SLS, but following that comes a reusable SpaceX Super Heavy/Starship combination. While SLS will fly first it may not fly for long given its excessive launch costs, and it could soon be relegated to an interim design. Elon Musk has been celebrating the launch hop of SpaceX test Starship SN-5 (after several explosive failures on land first). SpaceX could have a working rocket in, say, two years’ time.

The USA also has the Orion spacecraft – albeit serviced by an under-propelled service module (based on Europe’s ATV) which limits the lunar orbit it can reach to very high ones. The original plan was to use the Gateway – a man-tended lunar space station in a high lunar orbit – from which a reusable landing craft, with a transfer stage, would move astronauts back and fore to the lunar surface. However, in a rethink, NASA has decided that while it needs this architecture for the long term, the Lunar Gateway will be put on the back-burner as it concentrates on lunar landing craft. But these will still need a transfer stage to reach Orion.

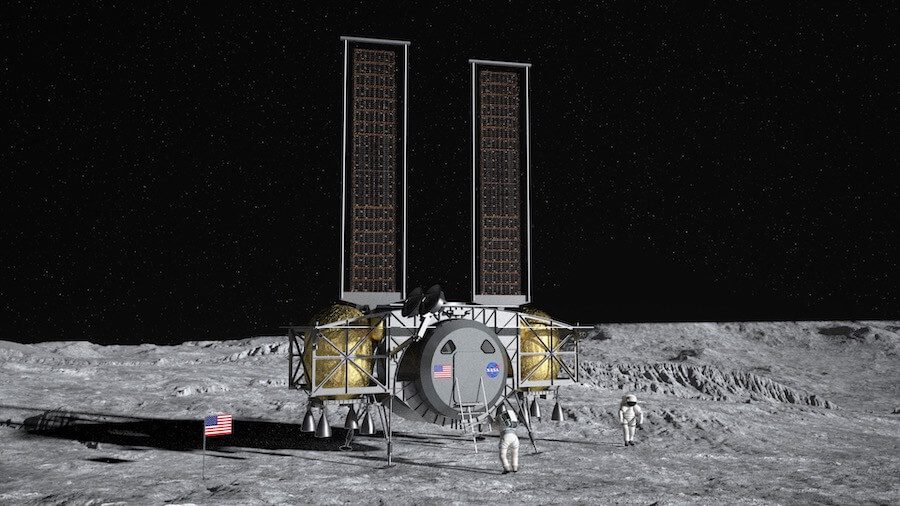

The Blue Origin-led National Team’s concept for a three-stage lunar lander/ascent/transfer craft. Courtesy: Blue Origin

With some hoopla NASA announced that three large lander designs of greater than 45 metric tons were going forward. The most conventional vertical-staged design was from the Blue Origin led National Team, which has just presented a mock-up to NASA. A more innovative type was offered by the team led by Dynatics, which used a more horizontal “Space 1999” lander concept.

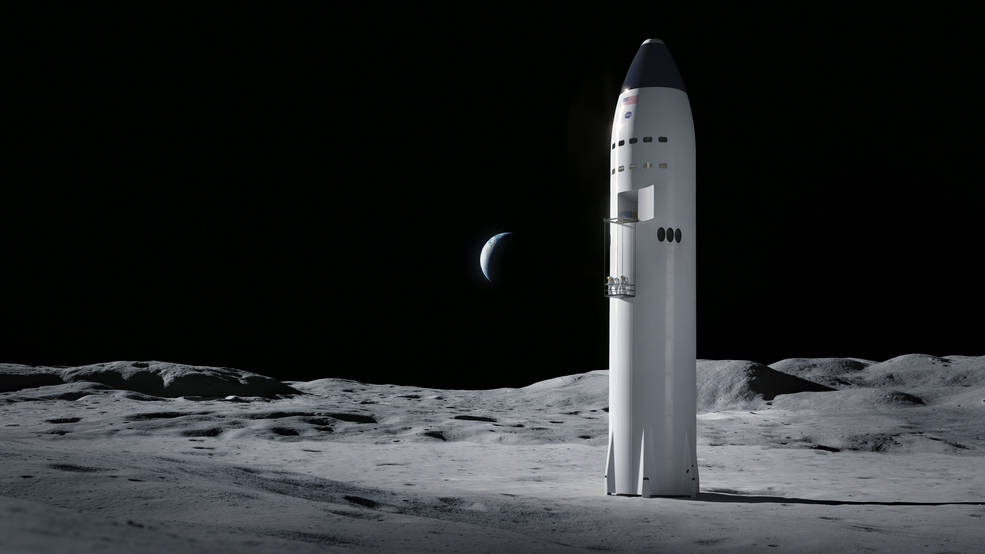

SpaceX’s Starship was the final of the three entries accepted. For the time being NASA just wants to use Starship as a pre-positioned lunar lander to meet up with its landing crew in high lunar orbit, carried there via the NASA Orion/SLS combination. However, it is known that Musk eventually wants to carry passengers from Earth to the lunar surface and back, using the SpaceX Starship/SuperHeavy rocket combination.

There is, however, a downside to all three designs. In catering for long term re-usability, all three teams are designing quite hi-tech cryogenic (LOx/Methane based) propulsion and storage systems whose technology readiness is doubted by NASA. The White House’s target date of 2024 for a lunar surface return looks unlikely to be met by these designs.

But something strange has happened. NASA failed to get the funding from Congress it wanted to build its preferred reusable lunar landing designs, and may now be forced back towards a much simpler and smaller 25-35 metric ton interim expendable “quick and dirty” design using storable/hypergolic propellants – a sort of son of the Apollo LEM (Lunar Excursion Module). If NASA did this, 2024 is entirely possible.

One thing that has yet to be set is how to get there. The SLS Block 1 does not have the capability to take even a small lunar lander with it, nor will the proposed Block 1B version using the four RL-10 engine EUS (Exploration Upper Stage). In other words, two heavy-lift launches would be needed – one for Orion and one for the lunar lander.

An alternative might be to use SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, along with the ICPS (Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage) that SLS Block 1 currently uses, to launch the lunar module component in unmanned condition just before a single SLS flies the Orion. While NASA studies showed that the Falcon Heavy/ICPS combination did not have the capability of taking Orion to the Moon, it probably does have enough TLI (Trans Lunar Injection) payload capability to carry a small lunar lander and its transfer stage to a high lunar orbit. The idea would be that Orion would dock with a lunar lander and transfer the crew ahead of a landing.

Some (Robert Zubrin et al) have even mooted that the SpaceX Crew Dragon might be used as a crew transfer vehicle in lieu of the Orion, but that is unlikely given that NASA is now set on the Orion/SLS combination. Nevertheless, with its controversial sidewall-mounted super-draco “escape” engines, the Crew Dragon could yet be repurposed as a lunar landing and/or ascent system. While not ideally located from a safety perspective, these Super Draco engines were placed there to allow vertical powered landings on Earth and even on Mars.

In the meantime, Musk is still keen going to Mars as well as going back to the Moon. Following the recent successful Starship hop Musk said: “We’re going to go to the Moon. We’re going to have a base on the Moon. We’re going to send people to Mars and make life multi-planetary.”

Seradata agrees with the Moon first concept but we suggest that NASA should make a Mars one-off mission BEFORE it gets bogged down building a base on the Moon – even if the Moon is where the real long-term economic potential lies in mining, research, tourism and astronomy. In reality, whatever Musk’s aspirations for a Las Vegas-style colony among the deserts of Mars, in the nearer term the Moon is where the money is.

Thus, a quick human exploration of Mars is needed, if only to get it out of our system, before a lunar base/lunar village is created. It is an order of human exploration that has the backing of former Apollo 11 Command Module astronaut Mike Collins.

Concerning the Starship design, there are technical doubts about whether the aero-thermodynamic environment will let the non-blunt body Starship perform a direct re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere at Mach 36 (for comparison LEO re-entry is at Mach 25). A multi-manoeuvre aerobraking staged strategy might lessen these peak loads.

Musk still hopes to land Starship on Mars directly (a direct planetary entry into the thinner Martian atmosphere should be aero-thermodynamically achievable). But getting it off the Martian surface using propellants produced by an in-situ propellant production plant is much less practical in the short term. The alternative of sending return propellant ahead to Mars is also difficult given the boil-off problems with storing cryogenics. Other companies have come up with their own concepts for a Mars entry and landing system, with the one from Lockheed Martin looking distinctly like the Starship.

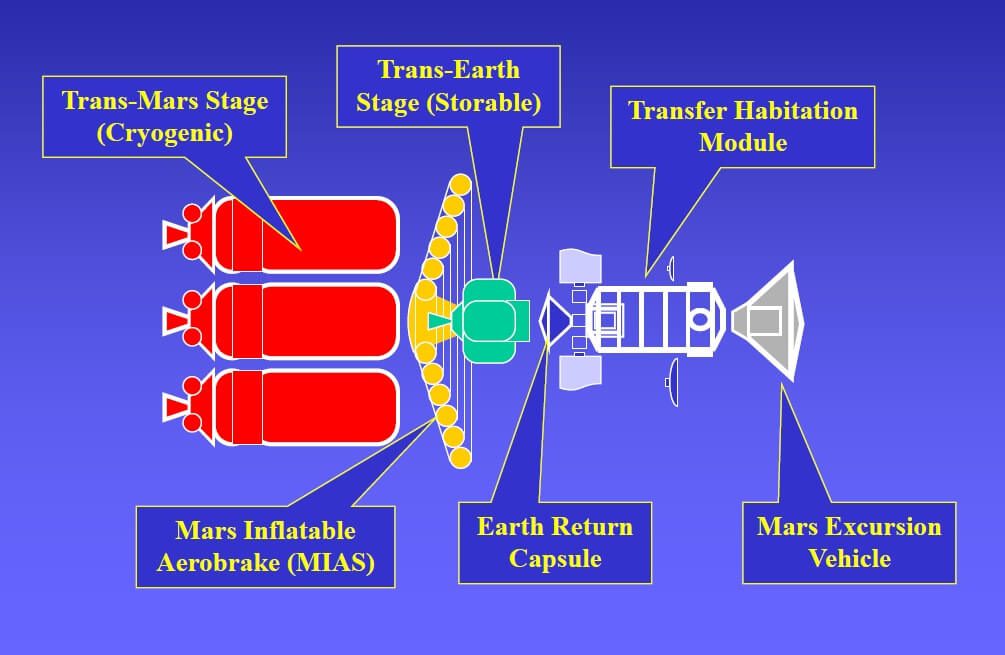

It is much more likely that a cut-down specialist landing expedition will be devised by NASA with a mission architecture looking more like the British Interplanetary Society’s simpler (and much cheaper) proposal from Professor Bob Parkinson. It uses a cryogenic outbound/storable propellant return architecture to achieve a basic human landing on Mars mission.

While we have our doubts about Starship’s application to a Mars landing and return, we admire the fact that Musk is building a quick-to-relaunch heavy-lift launch vehicle – essential for quick loading if boil-off is to be limited during any Mars mission.

Such a mission could be rapidly constructed and quick fuelled in low Earth orbit (avoiding significant boil-off problems) using a series of Starship/SuperHeavy flights. The trans-Mars stage of the Parkinson plan might be made up of fuelled-up Starship(s). In other words, it is entirely possible that a NASA-led human Mars landing mission could be made in the 2030s – about the time that China is due to land its Taikonauts on the Moon.

Bob Parkinson’s plan: elements needed for basic human landing mission to Mars. Courtesy: Bob Parkinson

China: Odds for human lunar return: 3-1 (25%). Odds for first human Mars landing: 9-1 (10%)

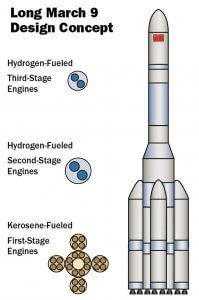

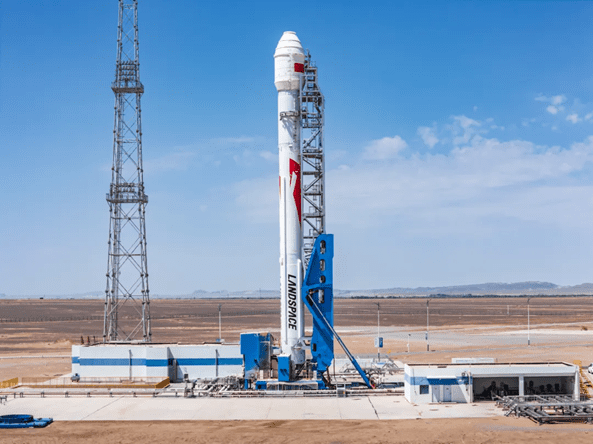

China still lacks a large launch vehicle – but is known to be working on its Long March 9 heavy-lift design and a human carrying lunar lander. However, in May China test-flew its next-generation crewed spacecraft, which is designed specifically to be able to return from the Moon. It still needs a lunar lander, which is thought to be under development using a throttlable engine technology (with the help of Ukraine). And it needs its Long March 9 super-heavy-lift launch vehicle – a kind of SLS Chinese style, albeit LOx/Kerosene based for its main and booster stages. China is working on a 1 million lb thrust class engine to power the first stage and boosters. The Long March 9 upper stage is cryogenic LOx/LH2.

In effect, the Long March 9 is a kind of Saturn V with a similar 50 metric ton payload to TLI. China’s lunar lander is reported to be about 30 metric tons.

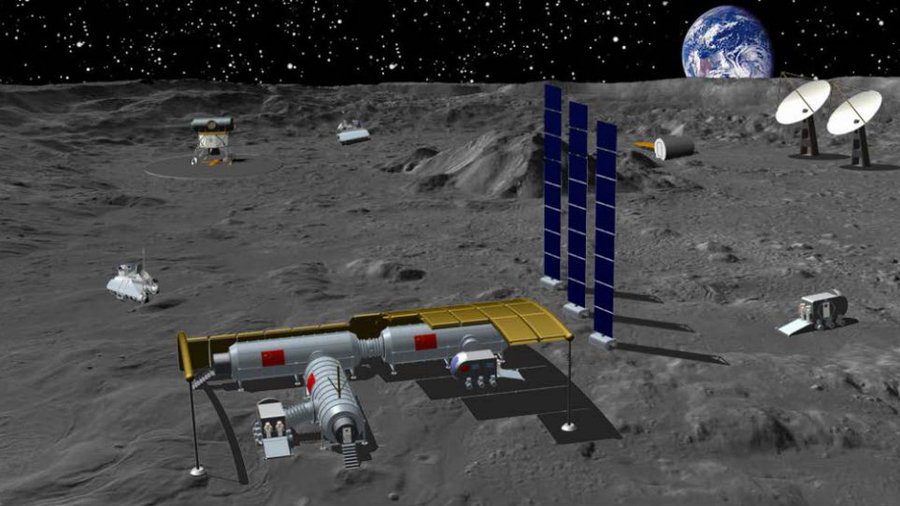

While it has plans to build an eventual Moon surface base, dubbed the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), at the lunar South Pole, current plans do not envisage a human landing attempt until circa 2030 – probably under the mission name Chang’e 9. As such, China remains very much the second favourite in both lunar and Mars races – albeit one that is ready to step in if, or when, the USA’s effort falls away.

Russia: Odds for human lunar return: 20-1 (<5%) Mars landing: 100-1 (<1%)

Meanwhile, Russia hopes to build a new large heavy-lift launch vehicle. It would like to team up with China but the latter wants to do its own thing. Meanwhile, political friction with the USA has dimmed its hopes of being part of the Artemis project. Russia has notionally committed to replacing its Soyuz human spacecraft with one dubbed the Orel, which will have the capacity for lunar missions. Likewise, it still lacks a heavy-lift rocket – despite being in possession of two in the Soviet era: the N-1 and the Energia (and even the one-man LK-3 lunar landing craft), although it is considering one called Yenisei.

The Russian LK-3 lunar lander (with a drawing of the N-1 rocket behind it) was only designed to carry one cosmonaut. Courtesy: Wikipedia

As such, Russia remains woefully behind the other leading space nations. Still, if it did concentrate its national resources, it could theoretically come up from the rear.

India: Odds for human lunar return: 100-1 (<1%) Mars landing: 1000-1 (<0.1%)

India has a human space programme, but has yet to launch anyone and the unmanned test flight of its crew carrying capsule has been delayed until next year. But it is likely, possibly with a few hiccups, eventually to succeed in putting an Indian gaganaut – male or female – into low Earth orbit. Is it equipped to reach the Moon or Mars? Probably not. Lacking a lander and a heavy-lift launch vehicle, it remains way beyond its capabilities to attempt lunar or Mars missions for several decades.

However, miracles can happen. And a very cut-down lunar lander using the current human carrying capsule could be mounted – much in the style of the Gemini capsule based Project Pilgrim – memorably shown in the Robert Altman movie Countdown (1968). Of course, getting an astronaut onto the moon is one thing… but getting them back is another. In the movie, the astronaut – played by James Caan – had to wait until his rescue by an Apollo landing craft.

Conclusion: USA leads easily but it has to stop its delays

Of the other nations, Europe and Japan are content to be part of NASA’s Artemis-led programme. So, in conclusion, the USA remains far and away the favourite in both races, although doubt remains about a return to the Moon in 2024. 2026 is more like it. China is still in the runner up position… for now.