The US Navy has used its Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) interceptor in action for the first time. SM-3s were used to shoot down Iranian medium-range ballistic missiles fired at Israel on 13 April in response to a fatal air strike, which Israel is widely believed to be responsible for, on the Iranian consulate in Damascus on 1 April.

US warships USS Arleigh Burke and USS Carney, located in the Eastern Mediterranean, fired missiles that were then guided to their targets by the SPY-1D radar, part of the Aegis defence system. SM-3s use a ‘hit-to-kill’ kinetic vehicle for the final interception in space. Israel’s land-based Arrow interceptor missiles are also thought to have made exo-atmospheric interceptions. It has not been disclosed which variants or block numbers of SM-3 were used.

Iranian drones flying slowly at low level were employed in the attack. These were intercepted by Israel’s short-range Iron Dome missile system and Israeli Air Force jet fighters, while its David’s Sling system intercepted shorter-range ballistic and cruise missiles. US Navy carrier jets and Cyprus-based RAF Typhoon jet fighters also intercepted Iranian drones heading for Israel. Impressively, of the 320 targets in total (170 drones, 120 ballistic missiles, 30 cruise missiles), 98 per cent were shot down, according to the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Five ballistic missiles did get through to strike Navatim air base, according to reports by ABC, but with only one casualty, a seven-year-old girl who was seriously injured by shrapnel/debris.

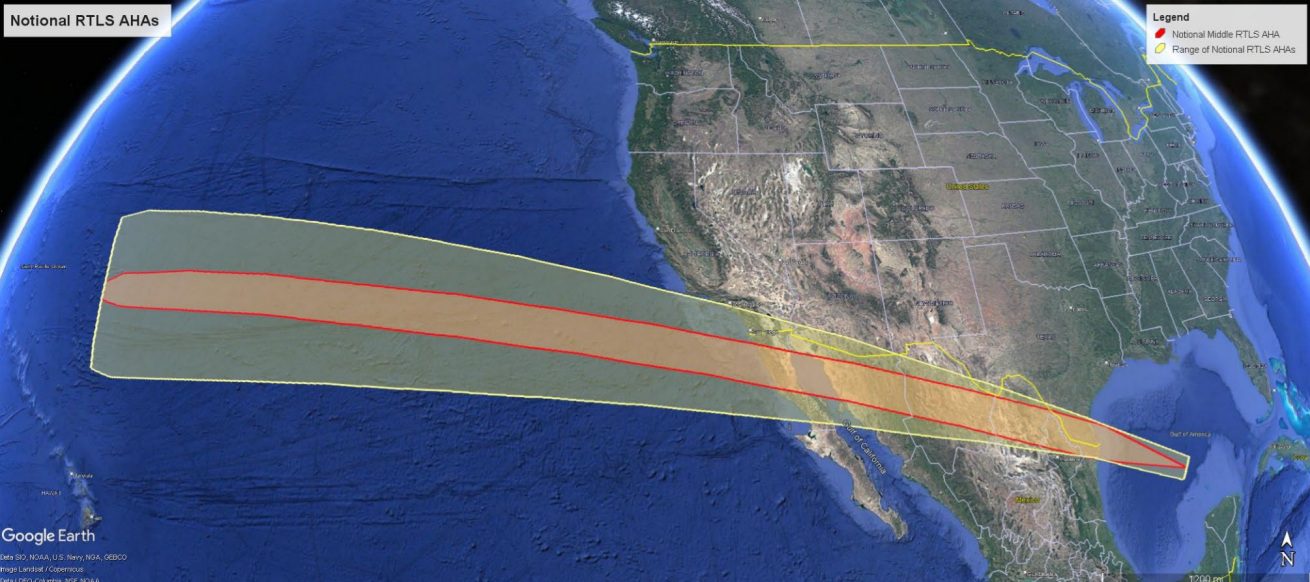

Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) test launch from US Navy ship. Courtesy: MDA

Anti-ballistic missile (ABM) interception systems

Anti-ballistic missile (ABM) interception systems have become essential for western naval defence. This has been propelled by the development of anti-ship ballistic missiles by the likes of China and Iran, designed primarily to take out large military ships such as aircraft carriers. However, ballistic missiles can also be used to attack commercial shipping, such as tankers and cargo carriers, as has been the case in Houthi rebel attacks in the Red Sea.

The Royal Navy has Aster 15/30, a well-regarded anti-aircraft missile system, but has yet to deploy an ABM version. Earlier this year, the UK Ministry of Defence announced that an ABM version would be fielded in two to three years.

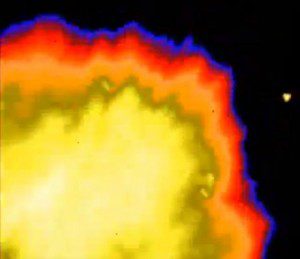

Fiery interception of target by Standard Missile SM-3 Block 1B in FTM-22 test. Courtesy: MDA

Global reactions

The missile and drone defence of Israel drew admiring glances from around the world – even from Ukraine whose anti-aircraft and anti-missile defences have also performed well. But not as well as the Israeli systems. European nations have realised that their missile defences need to be beefed up. For example, the UK gave up long-range land-based anti-aircraft missiles when the Bloodhound Surface-to-Air (SAM) missile system was retired in the early 1990s, and now only has short-range SAM systems.

Apart from the danger of retaliation by Israel on Iran, which could further escalate the conflict, US and UK involvement in the defensive action raises some inconvenient political and diplomatic issues. Some commentators have pointed out that while it was moral to save many Israeli civilian lives, western nations have not done the same for Ukraine, which has been under continual missile and drone attacks from Russia for more than two years.

Critics have also accused the US and UK of being, at best, inconsistent, given that an estimated 34,000 Palestinians (the majority civilians) have been killed by Israel’s armed forces during its incursion into Gaza. This was in response to Hamas’s killing of 1,200 Israeli citizens and its seizure of hostages. Under pressure from public opinion, the US and UK governments have themselves been pressuring Israel’s Netanyahu-led government to accept a ceasefire, albeit with little effect. Nevertheless, the US and UK decision to aid the air and missile defence of Israel has raised questions over their potential roles as ‘honest brokers’ in any peace-making negotiations in the Middle East.

Now retired: UK Bloodhound Surface-to-Air missile launch. Such was the performance of the Mk II version that it was even considered for anti-ballistic missile duty. Courtesy: UK MoD